The Washington Business Institute

Friday, November 18, 2022 by

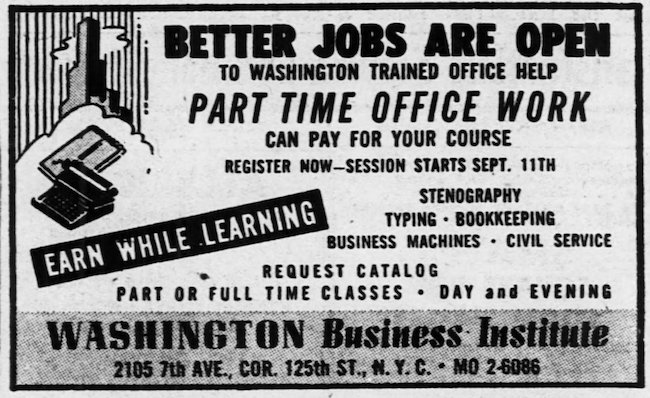

“Better Jobs Are Open to Washington Business Institute Trained Office Help” reads a 1950 advertisement on display in Analog City: NYC Before Computers at the Museum of the City of New York. Analog technologies created new opportunities, but many individuals couldn’t access them without a fight.

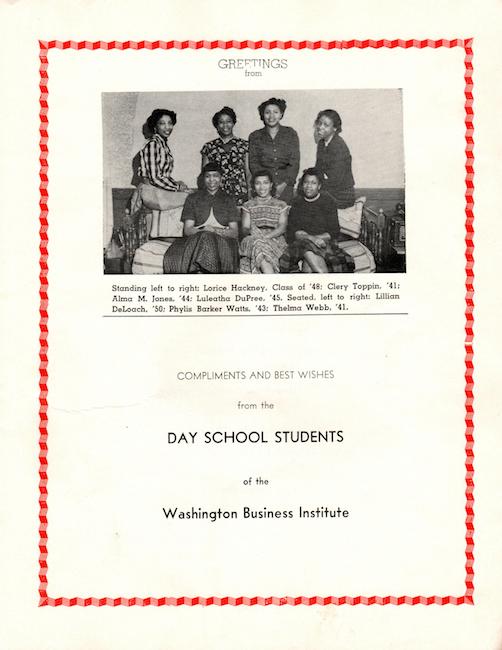

From its founding in Harlem in 1930 until its closure in Union Square in 1980, over 5,000 Black Americans, the vast majority of them women, learned typing, stenography, and bookkeeping at the Washington Business Institute, affectionately known as WBI. WBI was one of the first, if not the first, schools in New York City to offer full business programs to any student regardless of race. WBI staff and students helped lead the movement to integrate clerical work across the city and region. These jobs became mainstays for many Black New Yorkers—and especially African American women—long denied entry into middle-class professions.

Many of the growing numbers of African American and Caribbean migrants to New York City saw incredible promise in the relatively high wages and prestige of clerical jobs. So much so that Harlem Renaissance painter Vertis Hayes placed an African American woman typist at the very center of the portion of his Pursuit of Happiness (1937) mural at Harlem Hospital. Similarly, Lutie Johnson, the central character of Ann Petry’s acclaimed novel The Street (1946), took typing courses at night at the intersection of 7th Avenue and 125th Street, where WBI was located from 1933 until 1967. In the novel, Johnson sees clerical work as an empowering way for a single mother to escape poverty and achieve the American Dream.

In the first half of the 20th century, typist, file clerk, and stenographer positions were almost exclusively reserved for unmarried White women, as shown in the exhibition Analog City. Rae Feld, the daughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, founded the WBI after a school she taught typing for in Midtown refused to enroll African Americans in business courses. As the story goes, when Feld’s employer denied four African American women enrollment in February 1930, she quit and offered to teach the students on her own. With her father’s skeptical support, Feld rented two rooms on 125th Street and 8 Underwood typewriters. She named her nascent school after educational leader Booker T. Washington to signal that African Americans were welcome. 34 years later, when the Bronx chapter of the National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women’s Clubs awarded Feld the Sojourner Truth Award in recognition of her service to the community, she could boast that WBI changed the face of clerical work in New York.

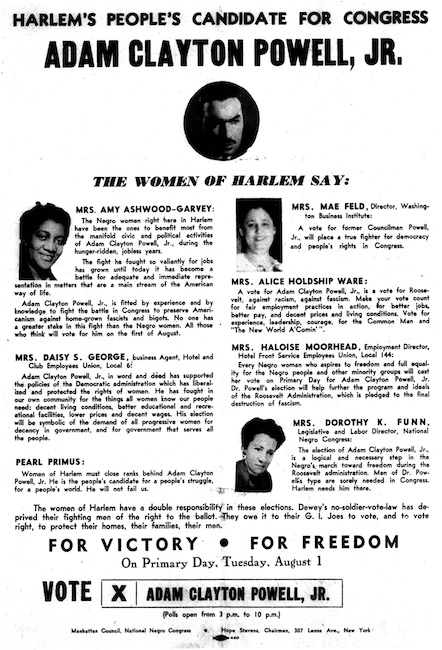

WBI had to be more than simply a school that taught skills. WBI staff and students had to agitate for access to well-paying jobs. WBI staff and students supported, and were supported by, Harlem political and religious leaders like Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., State Assemblymen William T. Andrews and Hulan E. Jack, City Councilman Benjamin Davis Jr., Rev. James H. Robinson of the Church of the Master, and Rev. Dr. John W. Robinson of St. Marks. WBI staff and students participated in “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns to boycott and picket Harlem businesses that refused to hire African Americans. WBI staff and students also supported the efforts of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and other groups to pressure Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to act on the lessons learned from the Mayor’s Commission on Conditions in Harlem after the riots of 1935. While White city leaders ignored most of the Commission’s recommendations for combating the devastating effects of segregation and discrimination, they did agree to dismantle some of the barriers in place against hiring African American administrators, clerks, typists, and stenographers in city agencies. Many applicants trained for these positions and prepared for civil service exams at WBI.

WBI became a cultural center as well. The school was located in the very heart of Harlem, down the block from the Apollo Theater, across the street from the Hotel Theresa, and above Lewis H. Michaux’s African National Memorial Bookstore. Graduation ceremonies and alumni association dances served as important community events with speakers like activist Cyril Philip, Catherine E. Ricketts of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and Dr. Lawrence Dunbar Reddick, curator of the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature and History at the New York Public Library. WBI students – the vast majority of them women - formed literary societies, art clubs, and reading groups that organized orations, performances, fashion shows, and exhibits. WBI Manager Florence K. Norman founded the Lambda Kappa Mu sorority for business and professional women in 1937. Five years later, WBI alumni also helped form the George Washington Carver School in Harlem, which offered low-cost adult education to those unable to attend high school and college. WBI hired preeminent Harlem photographer Austin Hansen to document graduations and exhibited the early work of portraitist and muralist James Ira DeLoache.

In a 1985 oral history, Feld explained why clerical skills were so important for many African American New Yorkers in the mid-20th century:

The story I always told the girls: whatever you get in here, nobody can take away from you. If you have to go back and clean, if you're cleaning with something in your head, you won't stay cleaning. Things will happen. World is growing. Things change. If you know how to type, you'll get a job.

While the political and social pressure WBI staff, students, and allies put on NYC employers throughout the 1930s to integrate their clerical staffs lay important groundwork, Feld remembered that it was World War Two that really broke open the field for her students.

The war effort required thousands and thousands of typists, stenographers, and bookkeepers. Nevertheless, racism continued to shape hiring practices. While most employers sought to employ those who could type at least 60 words a minute, WBI staff knew they needed to prepare their students to be twice as good and to type at least 100 words a minute or even 120 for especially prestigious positions. Some of this was because WBI staff knew students would be nervous demonstrating their skills, so they might type more slowly. However, they also knew that many White employers were looking for any excuse they could to not hire African Americans. As a result, WBI graduates earned a reputation for being superior typists and stenographers.

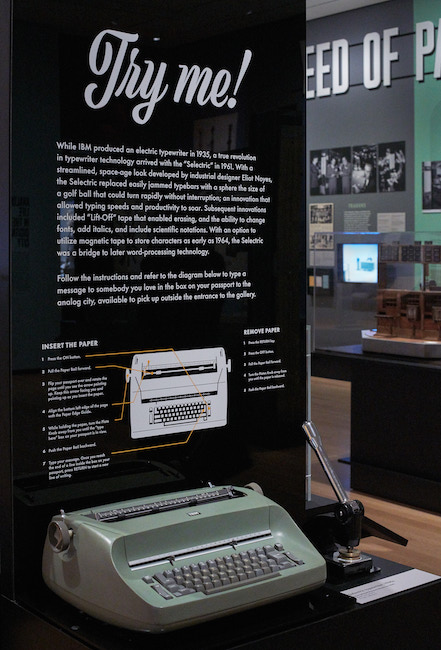

On display in Analog City is a 1961 IBM Selectric typewriter that visitors can try. Unlike the typewriters WBI graduates would have used in the 1940s, the Selectric utilized a spherical typing element that allowed for vastly increased speeds. Regardless, between breaking lines manually and the pressure needed to engage each letter, 120 words a minute on a Selectric is difficult. So, imagine typing at such a rate on a 1930s or 1940s machine under the scrutiny of a hostile hiring committee!

During World War Two and beyond WBI classes ballooned in size, graduating hundreds of clerical workers each year into stable middle-class jobs. WBI graduates went on to become the

first African American clerks hired at Governor’s Island, Brooklyn Army Terminal, Chase Manhattan Bank, Gimbel’s department store, and so on. As a result, the WBI alumni association, long guided by early graduate Vertella Valentine Gadsden, also became a powerful economic, cultural, and political force across the city and region.

WBI persevered in Harlem until 1967, when the space the school had rented since 1933 was demolished to make way for the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Federal Office Building. At a new location down in Union Square, WBI staff embraced emerging computer technology and a changing economic landscape. However, as the Selectric typewriter on display suggests, the shift towards new and eventually digital technologies increasingly changed the scope of job training. Given the need to revise their curriculum, and the fact that WBI no longer primarily served Harlem or African American communities, school leaders decided to sell the business in 1980.

Analog City illustrates the relationship between technology and society, and WBI’s 50-year history echoes that message. Technological developments did not automatically deliver opportunities equitably. Instead, WBI students seized their promise for their own purposes.

The history of WBI should be better known. But when WBI closed, many of its records were scattered. Gathering more information about WBI’s clearly remarkable and dynamic students will help document an important period in New York City and national history. It will also preserve hard-won lessons for another generation of students facing unequal access to technology and education today. If you have information about or a connection to WBI that you are willing to share, please contact the author at dylan.yeats@nyu.edu or on www.dylanyeats.com.

Dylan Yeats is a historian, curator, archivist, consultant, and tour guide based in Brooklyn. He is also the great-grandson of Rae Feld, founding Director of the Washington Business Institute in Harlem.