How to Curate an Interactive History Exhibition in 11 Easy Steps

(The New York City Version)

Monday, August 28, 2017 by

Rhythm & Power: Salsa in New York presents the vibrant story of New York salsa from the 1960s to the present. It’s also an ongoing, experiential project that includes over 20 unique programs, from an oral history project to professional development, walking tours, an intern mentorship program, film screenings, dance/music technique workshops, SummerStage programming, conferences, concerts, journal publications, and even painting courses. Rather than exhibition add-ons, this programming series serves to reach, excite, and connect communities throughout the global metropolis that is New York City. Thanks to talented staff and our communities, the programming is the most extensive series on salsa ever created. As the curator of this project, it has been a joy to witness the programs blossom into thriving centers of learning that reverberate inside and beyond the Museum’s walls. I kept a journal of some of the lessons I learned along the journey, and I would like to share some of these insights with you here.

Some of the most important lessons I learned during the curatorial process:

1) Travel: The Story of New York Salsa Leads to Unlikely Places

Like many of the venerable music genres hatched from cross-cultural interactions on the streets and nightclubs of NYC, New York salsa’s roots lie in hybrid cultural traditions from West and Central Africa, Western Europe, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico City, the United States, and other locations. My research trips and participation helped inspire the exhibition’s floor installation that offers a dizzying graphic of genres that influence New York salsa.

2) Know Your People: Know Your Audience

It’s important to know who you’re working with. Before the exhibition opened, I produced several different programs that strengthened relationships between NYC communities and the Museum. The oral history project, Dance Culture in NYC, invited artists that have performed and taught for several decades. The New York Meets Havana party connected Cuban, Puerto Rican, Colombian, and New York City dance communities that have their own unique histories of what we now call salsa. These programs brought communities together while also informing curatorial decisions for the exhibition.

3) New York City=All City

To fully understand the story of New York salsa, I traveled throughout the city to witness the different ways in which people, artists, and communities interpret this living tradition. From the Lower East Side casitas (communal recreational structures that resemble old country homes in Puerto Rico), to “el condado de la salsa” (county of salsa) that is the Bronx, I began to understand local cultures and how the music created artistic bridges across NYC. East Harlem, also known as El Barrio and South Williamsburg, affectionately called Los Sures, are also home to vibrant communities that reveal the ways salsa continues to inspire creative experimentation in NYC. Ridgewood, Queens and Bushwick, Brooklyn are not just geographic outposts, but offer amazing opportunities to learn about the inter-ethnic relationships that continue to shape the sounds of New York salsa. Staten Island has a proud Puerto Rican community that celebrates salsa, and several different genres of Latin music like no other borough. By traveling throughout NYC, I understood the place-based narratives that make New York salsa unique.

4) The Importance of Libraries and Archives

Libraries and archives are a great means from which to learn about the scholarly conversations surrounding salsa. It takes some getting used to it, but the libraries and their special collections are generally open to anyone. I had to submit special requests to use their work; however I was able to access the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives at New York University. The Center of Puerto Rican Studies and Centro Library offered additional materials. The New York Public Library of the Performing Arts provided a trove of video and sound recordings found nowhere else in the world. I spent several days in the temperature controlled rooms with fancy white gloves at the Museum of the City of New York. Archival staff shared club brochures, including some that hadn’t been touched for decades.

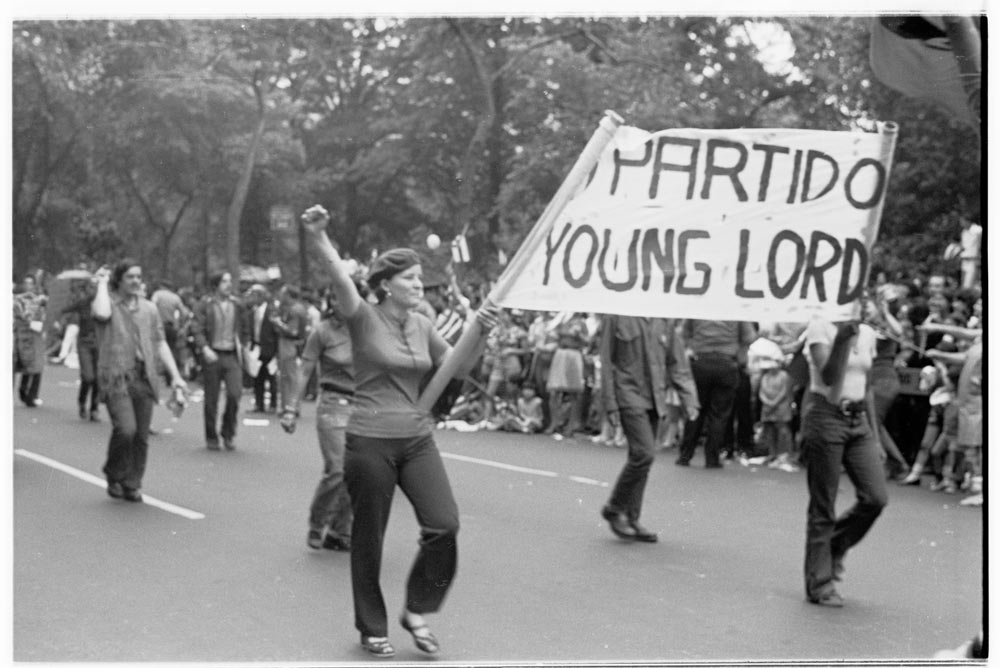

5) Treasure Troves in NYC Tenements

I found a lot of information that did not live in archives. Máximo Colón, a prolific photographer shared boxes of photos that document NYC culture, from the political activism of the Young Lords to salsa musicians. His apartment is filled with reels of negatives and photos developed with a level of precision not usually seen in our digital age. As he opened up dusty boxes, memories of protests that addressed injustices such as health care, affordable housing, and garbage pickup spilled out onto our laps. Here is one of the photos we found:

6) Ethnography

Participant observation/sharing was one of the most rewarding aspects of research for the exhibition. Through my work in the ‘field,’ I was able to visit Eddie Torres in midtown Manhattan while he was teaching his technique that is one of the most widely practiced styles of salsa dancing in the world. I also met musician Luis Mangual Jr. while he was playing at the Lincoln Center Atrium. This started the relationship that allowed for the loan of his grandfather, Jose Mangual Sr.’s, bongos, now featured prominently in the exhibition. Mangual Sr. played with Machito and his Afro-Cubans (b. 1930–2003). Mangual passed those bongos on to his two sons, Jose Luis Mangual Jr. (b. 1948) and Luis Jose Mangual (b. 1948). Mangual Jr. played bongos on some of Willie Colón’s, Héctor Lavoe’s, and Rubén Blades’s most well-known recordings. Luis Jose Mangual played for Johnny Pacheco on some of his most significant Fania recordings throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Jose Luis Mangual’s son, Luis Mangual Jr. (b. 1966), plays with several New York bands, including the legendary Orquesta Broadway.

7) If You Can Walk, You Can Dance

Rhythm & Power places the practice of music and dance as central to understanding the genre. The story of salsa cannot be understood completely without some participation in the lively, communal dance culture that the music supports. I celebrated at the 116th Street Festival that happens in June. I danced at the 111th Salsa Street Party and Old Timer’s Stickball Game. Salsa Sundays at Orchard Beach in the Bronx are a must for anyone interested in the ways salsa is practiced in local spaces. Also be sure to keep an eye out for the Three Kings Day Parade, The Loiza Festival in El Barrio, the Loisaida Festival in the Lower East Side, and the impromptu block parties that pop-up on city streets. I went to the “on2” dance socials held by some of the top dance schools in New York City. Each have their own distinct flavor and style. From Lorenz Dance Studio on 110th and 2nd Avenue in East Harlem to Huracán Dance Studio in Corona, it was amazing to witness how studios facilitate deep, familiar connections. Lastly, the distinct sounds of the Cuban music parties helped provide nuance to the constantly evolving scene of salsa music in NYC.

8) Communication

Communication is key to curating a community-based exhibition. Your job is not solely about decision making and placement, but rather about creating and maintaining a complex web of contacts and conversations through persistence, time management, inventiveness, charm, and compassion. I may have had to cut some calls short when talking to people on calling cards in Cuba. Coordinating time to speak with leading trombonist Jimmy Bosch, who was doing pioneering work in Japan, was not easy. But persistence with individuals such as Eddie Palmieri’s sons helped secure loans that created a story rather than simply a memorabilia store.

9) Tell Stories to Humanize

We know many of the legendary musicians in salsa by name. By building relationships and trust, I was able to humanize these legends. Talking to Margaret Puente, the widow of the late Tito Puente (1923–2000), I learned about the shoes she bought in Indonesia that she believed would add style to his wardrobe, similar to that of Frank Sinatra. Through a personal anecdote such as this, patent leather shoes opened a more personalized story of Tito Puente as a man negotiating his place in the music industry and the world.

10) Think Outside of the Box (it just might work!)

Thinking outside of the box with respect to presentation and education can bring some unexpectedly golden results. The interactive dance projection shows the movements that differentiate New York “on2" style of dancing from other salsa dance styles. There were initially concerns about having space in the hallway and the noise levels, however, in the end, our flexibility allowed for one of the most popular aspects of the exhibition.

11) Make Connections

Instead of just having items in an exhibition, find ways to connect the story. Working with the Celia Cruz Legacy Project, Larry Harlow, Fania Records, and collector Pablo Iglesias, I was able to share the story of one of Celia Cruz’s first large performances in the United States. Ms. Cruz performed in Larry Harlow’s Hommy in 1973 at Carnegie Hall. She worked with Johnny Pacheco and helped expand the musical capabilities of the sounds that Fania Records and Latin NY’s Izzy Sanabria promoted as a new genre. Her inclusion in the story demonstrates the circular flows of culture and ideas between Latin America, Caribbean and New York City.

Conclusion:

Rhythm & Power shares the diverse voices that helped inspire New York salsa. The positive reviews in English and Spanish media are a testament to the need for future exhibitions that speak to the cross-cultural complexities that make New York, and the United States, unique. As the exhibition remains on view (until November 26, 2017) and the upcoming special edition book published by the CUNY Center of Puerto Rican Studies, we will continue sharing this living culture with the world. Please stay tuned as I share additional tips in future blogs. Adelante!