ACT UP, HIV/AIDS, and the Fight for Healthcare

Thursday, July 6, 2017 by

On Sunday, June 25, 2017, members of the HIV/AIDS activist group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) marched in New York City’s annual LGBT Pride march. They carried black coffins, bearing the names of services that have been endangered by the Trump administration and the Republican-led Congress: the Ryan White CARE Act (passed in 1990, it is the largest federal HIV program); PEPFAR (President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, established in 2003, providing HIV/AIDS services globally); and Obamacare, or the Affordable Care Act, under threat of repeal and replacement in the coming weeks.

ACT UP is one of many New York groups featured in AIDS at Home: Art and Everyday Activism at the Museum of the City of New York. The group celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, but its underlying message could not be more relevant: the politics of healthcare have life and death consequences.

ACT UP was founded in March 1987 after writer and activist Larry Kramer critiqued the LGBT community for its complacency. Since the first cases of AIDS were diagnosed in 1981, many grassroots organizations in the city had created pioneering and essential services to support people living with AIDS, but rates of AIDS-related illness and death continued to rise. At a lecture at the Gay and Lesbian Center in the West Village, Kramer called for the creation of a direct action group to protest government agencies and drug companies for their slow and inadequate response. In the decade to come, ACT UP New York staged countless demonstrations throughout the city—from City Hall to St. Patrick’s Cathedral—and spurred the creation of ACT UP chapters across the United States and Europe.

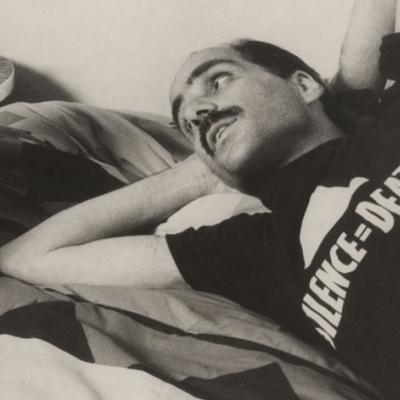

One of ACT UP’s greatest accomplishments was pushing government agencies and drug companies to accelerate testing of medications, lower the costs of existing drugs, and bring people with HIV/AIDS into the process. By 1996 new antiretroviral treatments dramatically changed the prognosis for people living with HIV, making it possible for many people to live long-term with the virus.

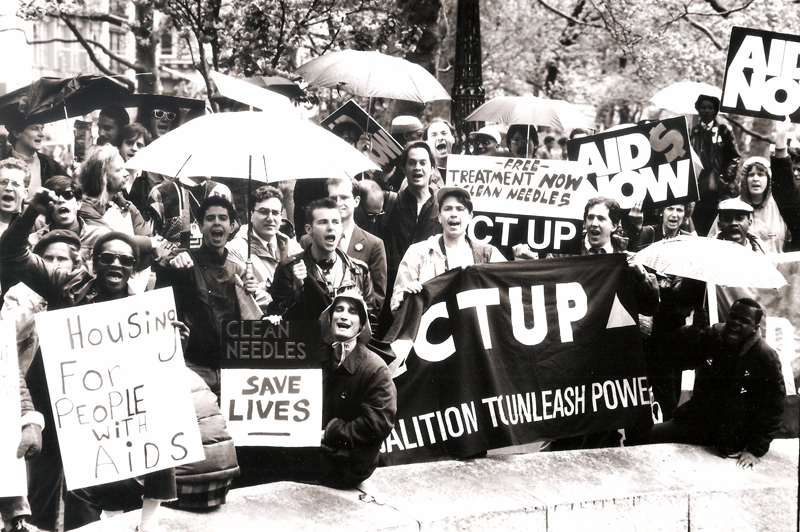

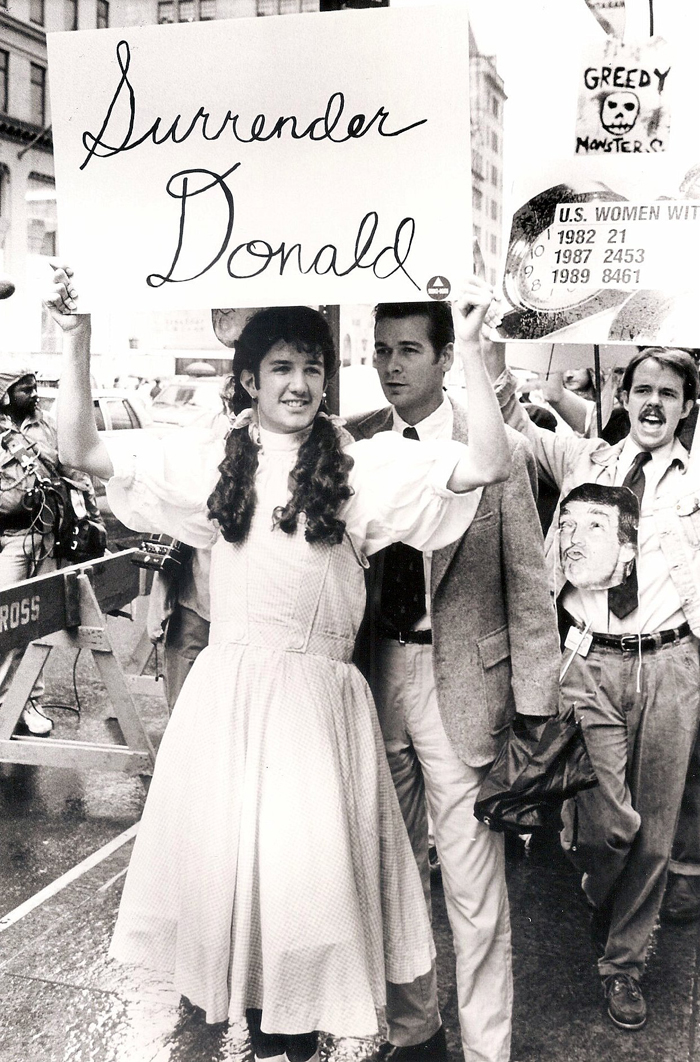

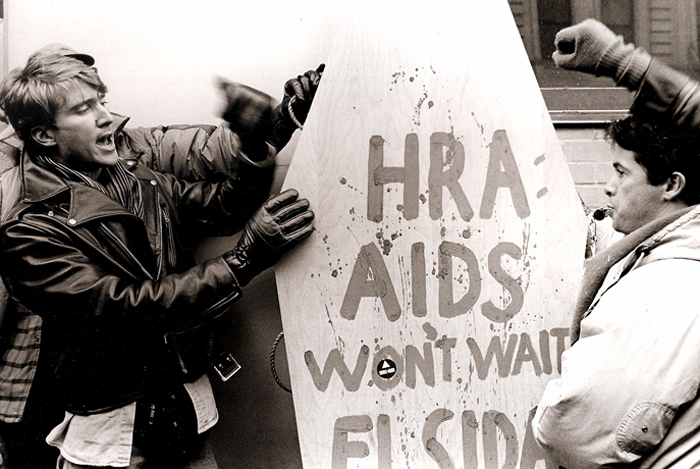

But ACT UP also had a uniquely expansive view of healthcare. As photographs by Lee Snider, a featured artist in AIDS at Home reveal, ACT UP demonstrations integrated and drew connections between a range of issues that impacted people with HIV/AIDS: treatment access, housing, needle exchange, insurance, government inaction, corporate greed, and social stigma. They also developed smaller “affinity groups” to lead targeted actions: as I wrote about last December in Slate, for example, the ACT UP Housing Committee led a demonstration at Trump Tower on Halloween in 1989 to protest city policies that prioritized developers like Trump, at the same time 10,000 people in the city who were living with AIDS and homeless.

The action at this year’s LGBT Pride march also recalled many ACT UP demonstrations from the 1980s and 90s: activist Tim Bailey, for example, was given a public funeral in front of the White House at his own request, but friends clashed with police when they tried to remove his casket from their van, as recorded by James Wentzy. In another protest—part of a series of city-wide demonstrations on January 23, 1991, declared by ACT UP a “Day of Desperation”—activists carried wooden coffins through downtown Manhattan and delivered them to city, state, and federal officials to protest government inaction.

Other groups were less visible. Karin Timour recalled in an interview with the ACT UP Oral History Project how the Insurance and Healthcare Access Committee worked with the healthcare coalition New Yorkers for Accessible Health Coverage to change state laws governing insurance. That work ultimately enabled greater access to health insurance regardless of preexisting medical conditions—an important precursor to the ACA.

ACT UP demonstrated the urgency of building a healthcare system designed to meet the needs of the most vulnerable. For people living with HIV/AIDS today, that sense of urgency remains, only there is far less public discussion. Linda Villarosa’s recent cover story in the New York Times Magazine shows that the highest rates of HIV in the world today are among gay and bisexual black men in the United States. The majority of HIV cases overall are in southern states, where there are far fewer support services and government programs for people with HIV/AIDS than there are in New York City. And only 40% of people living with HIV can access the medications needed to manage the virus. People living with HIV will only be put at greater risk if the Republican healthcare plan passes—with Medicaid cuts making it more difficult for poor people to access medications, and reduced insurance regulations making it easier to deny coverage to people with preexisting conditions including HIV/AIDS. The history of ACT UP should be instructive for our own moment, not because the battle they waged for healthcare was won but because it never ended.