You Are Here

You Are Here: An Immersive Film Experience

New York is one of the most filmed cities on earth. Generations of moviegoers have seen New York depicted and distorted, celebrated and denigrated, idealized and mocked, built up and demolished over and over again on the big screen. Over the past 100 years, legions of filmmakers have drawn attention to New Yorkers’ joys and struggles, shaping our ideas of what the city is—or could become.

YOU ARE HERE draws on this rich archive of movies set in New York, combining thousands of cinematic moments across 16 screens. Sources include Hollywood blockbusters, independent films, documentaries, and experimental works. By juxtaposing these multiple visions, the dazzling montages of YOU ARE HERE make connections and contrasts that allow movies to comment on each other across time and space. Together, they shed new light on the varied New Yorks of our collective imagination.

Sometimes New York stars in these movies; sometimes, a studio set or even another city stands in. In the introductory room, Scenes from the City explores the city as a film set, showing how movies have been captured on location throughout the five boroughs. From there, we invite you to enter the immersive central space, where you can explore a narrative tapestry woven from hundreds of films—one impressionistic storyline that strives to represent the multifaceted realities of our countless New York stories.

SCENES FROM THE CITY: FILMMAKING IN NEW YORK

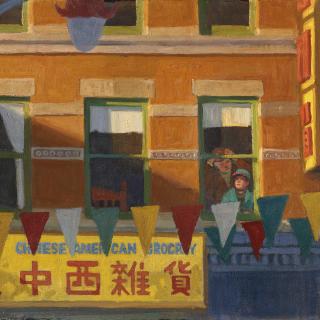

Since the birth of the film industry over a century ago, New York has been one of the world’s most popular settings, subjects, and sources of inspiration for moviemakers of all kinds. But New York has not always been the location of the actual shooting. In the early 20th century, silent films were shot on location all over the city, but the arrival of sound in the late 1920s shifted feature film production almost entirely to Southern California, where an extraordinary invented New York was brought into being on the stages and backlots of Hollywood studios. It was only in the years after World War II that filmmakers returned to the streets and sidewalks of the real city, and a New York-based film industry arose again.This gallery highlights behind-the-scenes stills of feature films being made in the city since the 1940s. The images reveal how advancing technology, the creative aspirations of filmmakers and performers, innovative governmental agencies, and the abiding worldwide appeal of New York as a filmic setting have combined to produce a dynamic, ever-evolving portrait of the city’s physical landscape, cultural richness, and social complexity.

Top

Play Ball

Unknown photographer, 1925

Reproduction

Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

In the movies’ silent period, lightweight cameras, the extensive use of natural lighting, and the absence of sound equipment allowed filmmakers to roam freely across the real city’s landscape. In this view the actress Allene Ray hangs from a false parapet atop a roof in the West 40s of Manhattan, with only a mattress below to offer some minimal protection.

Left

The Fountainhead

Unknown photographer, 1949

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

To recreate the Manhattan skyline on Hollywood soundstage sets, art directors produced colossal scenic paintings called “backings.” In this shot, taken between setups at Warner Bros., grips remove a backing behind the desk of the New York press baron played by Raymond Massey.

Middle

Life with Father

Jack Woods, 1947

Reproduction

Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

In the studio era of the 1930s and ’40s, every Hollywood backlot included a “New York Street” set, with false facades lining a central street and sidewalk. For Life with Father, set in the 1880s, Warner Bros. built a stretch of Madison Avenue rowhouses on their lot in Burbank, California.

Right

Broadway Melody of 1936

Unknown photographer, 1935

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

The Hollywood studio era’s “mythic city” came to a pinnacle in the glamorous rooftop nightclubs that seemed to top every skyscraper in Manhattan. Here a crew films Eleanor Powell on an MGM nightclub set, surrounded by a curved scenic backing known as cyclorama.

HOLLYWOOD COMES TO TOWN

In the years after World War II, a handful of pioneering Hollywood filmmakers began shooting movie scenes—and in some cases entire movies—on location in New York City. Their work was enabled by technical improvements in cameras, film stock, and lighting and sound equipment and encouraged by the changing tastes of audiences, who sought a greater degree of realism after exposure to wartime newsreels and documentaries and postwar neorealist features from Europe. Hollywood studios brought directors, actors, and crews to the streets and spaces of New York City to capture their fictional narratives on the real urban landscape.

Top

The Naked City

Stanley Kubrick, 1948

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

The first studio feature to be made primarily in New York in two decades, this film was shot over the summer of 1947 on 107 locations (including this chase on the Williamsburg Bridge). The logistics pushed the film a half million dollars over budget, but its enormous popular and critical success demonstrated the appeal of New York as a film location.

Left

On the Town

Unknown photographer, 1949

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Though the film was made mostly at MGM studios in Hollywood, its ten-minute “New York, New York” number broke ground as the first to synchronize music and dance on location. The sequence follows three sailors (Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra, and Jules Munshin) energetically touring the city—including Rockefeller Center, where crowds lined up to watch the filming.

Middle

The World, the Flesh, and the Devil

Unknown photographer, 1959

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

An interracial Cold War parable about the three survivors of an atomic attack, the film included haunting scenes of its star, Harry Belafonte, wandering the empty streets of Manhattan. They were either filmed between 5:30 and 6:00 a.m. before workers arrived or filmed upward, like this view in the Financial District.

Right

North by Northwest

Kenny Bell, 1959

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Though Alfred Hitchcock generally preferred to work in the controlled confines of a studio stage, he brought a crew to the real Grand Central Terminal to film Cary Grant trying to board a train unnoticed among the busy crowds of the Main Concourse. Hundreds of New Yorkers watch the shoot from the balcony, unseen by the camera.

THE MYTHIC CITY

By the 1950s and early ’60s, many of the most celebrated scenes in American movies were being created on location in New York. Iconic filmic moments once received by New Yorkers from a mysterious place a continent away—Hollywood—were now carved from the city’s own days, months, and seasons. From the frigid winter piers of On the Waterfront to the hot summer playgrounds of West Side Story to the balmy September sidewalk of The Seven Year Itch, legendary directors and famed stars transformed New York into a mythic urban place. Designed to appeal to national, largely white audiences and produced mostly by mainstream Hollywood studios, the new “movie New York” captured the world’s imagination—even if rarely reflecting the growing ethnic and racial diversity of the city itself.

Top

West Side Story

Ernst Haas and Phil Stern, 1961

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Choreographer and director Jerome Robbins demonstrates a dance move to George Chakiris (left) and Jose De Vega. Shooting on tenement blocks about to be demolished for Lincoln Center, the filmmakers used the city’s locations to bring a documentary-style authenticity to their Hollywood production. Like nearly all studio-made films of the era, it cast mostly white actors (like Chakiris) to play its Puerto Rican and other non-white characters.

Left

West Side Story

Ernst Haas and Phil Stern, 1961

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Before the cameras rolled each morning, New Yorkers were amused to see the film’s supposedly violent teenage gangs performing classical ballet exercises, using a tenement railing as a makeshift barre.

Middle

On the Waterfront

Unknown photographer, 1954

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

For his film about corruption in the Port of New York and New Jersey, the director Elia Kazan brought his crew to Hoboken, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from Manhattan, to shoot on its streets, its piers, and a tenement rooftop—where in this image Kazan, kneeling at center, speaks with the film’s star, Marlon Brando.

Right

The Seven Year Itch

Sam Shaw, 1955

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

The most famous location shoot of the era was the September 15, 1954, nighttime filming of Marilyn Monroe on Lexington Avenue and 52nd Street, as the breeze from a subway grate lifted her summer dress. Thousands watched as director Billy Wilder (left) called for take after take—only to later replace the footage with a studio-shot version of the scene.

A NEW ERA IS BORN

By 1965 location shooting in New York was slowing down. Major studios—deterred by union pressure, costly police handouts, and uncooperative city agencies—produced only two features fully in the city. In May 1966 newly elected Mayor John V. Lindsay established the world’s first government agency of its kind, the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theatre, and Broadcasting, along with a special Motion Pictures Unit of the Police Department. The result was a sudden explosion in film production and the start of a new New York-based film industry, whose leading figures included independent filmmakers, directors from abroad, and a new group of Black directors, including Gordon Parks and Ossie Davis.

Top

A Thousand Clowns

Unknown photographer, 1965

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

One of only two features produced in New York that year, the film sought to “open up” the Broadway hit it was based on through extensive location shooting of its stars (Jason Robards and Barry Gordon) wandering around the city, including the aging East River piers shown here.

Left

Up the Down Staircase

Unknown photographer, 1967

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

In the first years after founding the Mayor’s Film Office, Mayor Lindsay made regular visits to New York shoots, including the East Harlem set of Up the Down Staircase, where he posed for photographs with the film’s young cast, star Sandy Dennis (pointing), and writer Bel Kaufman (seated).

Middle

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Unknown photographer, 1970

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Directed by the pioneering Black actor and filmmaker Ossie Davis, the film follows two detectives across the length of Harlem, offering a sympathetic portrait of the legendary district. Here a local crowd gathers to watch the filming of a charismatic funeral director in an old-fashioned morning suit.

Right

Midnight Cowboy

Martin Munkácsi, 1969

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

The flood of films shot in New York after the founding of the Mayor’s Office included many showing the city in a decidedly unflattering light. Directed by the Englishman John Schlesinger (in a dark shirt in the foreground), Midnight Cowboy portrayed a hustler from Texas (Jon Voight) whose attempts to solicit women include this moment on Park Avenue.

THE NEW YORK AUTEUR

The growth of a New York-based film industry soon gave rise to a new kind of American moviemaker, whose personal, location-shot films—which they often wrote and acted in as well as directed—turned the city into not only a setting but a subject. By the 1980s, three distinctively “New York” filmmakers, Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, and Spike Lee, seemed to embody the breadth of the city—from Scorsese’s lower Manhattan to Allen’s Upper East Side to Lee’s Brooklyn—as well as its range of Jewish, Italian, and Black cultures. Meanwhile, a fourth New York auteur, Nora Ephron, began bringing her own glowing vision of the city to the screen.

Top

Do the Right Thing

David Lee, 1989

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Spike Lee, the film’s writer, director, and leading actor—as a pizza delivery worker—is captured in a dolly shot as he walks down the Bedford-Stuyvesant block that is the film’s sole setting.

Left

Annie Hall

Brian Hamill, 1977

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

The now-controversial writer and director Woody Allen was also a leading actor in his Oscar-winning film, playing opposite Diane Keaton in the title role. In this view the two are filmed walking down East 70th Street on the Upper East Side, one of Allen’s preferred New York settings.

Middle

Taxi Driver

Josh Weiner and Paul Kimatian, 1976

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

The film’s location shoot across the summer of 1976—just months after the city skirted bankruptcy—was one of the most fraught and intense in the city’s history. In this view Martin Scorsese directs Robert De Niro and Cybill Shepherd in front of a pornographic movie house on West 42nd Street.

Right

You’ve Got Mail

Brian Hamill, 1998

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

The film’s director and co-writer, Nora Ephron, instructs the romantic leads, Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan, for the film’s climactic scene, shot in the 91st Street Garden in Riverside Park.

THE STREET AS STAGE

As actual New York streets replaced the backlot “New York Streets” of the studio era, the ordinary city block became a primary arena of movie New York, compressing the vastness of the five-borough metropolis into a compact, comprehensible, and surprisingly scenic setting. For filmmakers the street offered an ideal platform to capture the daily texture of life in the city—or serve as an impromptu stage for larger-than-life happenings. It could also provide an effective marker of the profound forces driving urban change—from disinvestment and abandonment to revitalization and gentrification.

Top

Dog Day Afternoon

Martin Munkácsi, 1975

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Directed by veteran New York director Sidney Lumet, the film was shot almost entirely on a single block in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn—not far from the site of the actual bank robbery that inspired the story. Lumet transforms the street into a kind of outdoor stage, with the robber Al Pacino as the star, detectives as supporting actors, and the raucous crowds of Brooklyn onlookers as the audience.

Left

The Landlord

Unknown photographer, 1970

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

As cinematographer Gordon Willis (with framing lens on chain) looks on, a wealthy suburbanite (Lee Grant) warily greets the tenants of a rundown rowhouse on Prospect Place in Brooklyn’s Park Slope—still a poor, largely Black neighborhood at the time— that has been purchased by her son, played by Beau Bridges.

Middle

Jumpin’ at the Boneyard

Unknown photographer, 1991

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

A camera and dolly follow two brothers (Tim Roth and Alexis Arquette) on their journey through the burned-out streets of the South Bronx, still devastated from the epidemic of arson and abandonment of the late 1970s.

Right

In the Heights

Macall Polay, 2021

Reproduction

Courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. Director

Jon M. Chu shoots Lin-Manuel Miranda—the film’s composer and producer—playing a struggling piragua (shaved-ice) vendor on 175th Street in Washington Heights, a Dominican and Puerto Rican district at the northern end of Manhattan.

STELLAR GLIMPSES

As filming in New York grew ever more popular—propelled by the efforts of the Mayor’s Film Office, improvements to technology and logistics, the creative aspirations of directors, and audience preference—location shoots became a regular part of the urban landscape. New Yorkers and visitors commonly came across the production trucks, lights, cranes, booms, video playback equipment, harried production assistants, armies of craftspeople, and, not least, world-famous movie stars that marked a feature film in production. Some grumbled at the imposition. Others lingered excitedly to watch the stars, not only during the active scenes but, even more tantalizingly, during the quiet moments in between.

Top

The Pick-up Artist

Brian Hamill, 1987

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Taken between setups by the noted stills photographer Brian Hamill on a side street off Columbus Avenue on the Upper West Side, this view captures a contemplative moment between the film’s two leads, Molly Ringwald and Robert Downey Jr.

Left

Desperately Seeking Susan

Andrew Schwartz, 1985

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

During a break on location in the East Village early in the film’s shooting, Madonna—still a downtown cult figure—autographs a fan’s skateboard. During the ten weeks of filming, director Susan Seidelman later recalled, the popularity of Madonna’s music videos exploded and the set soon needed extra security.

Middle

Inside Man

Unknown photographer, 2006

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Between setups on a nighttime shoot on Beaver Street amidst the stony canyons of the Financial District of lower Manhattan, the film’s star, Denzel Washington, enjoys a private joke with director Spike Lee.

Right

One Fine Day

Gemma LaMana and Myles Aronowitz, 1996

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

In an off-camera moment while filming in SoHo, the film’s star, George Clooney, relaxes with a basketball and chats with a crew member while sitting in a folding wood-and-canvas director’s chair that has been a fixture of location shoots for a century or more.

ALTERNATIVE TRADITIONS

Even as studios increasingly produced their major releases in New York, alternative traditions flourished on its streets. Dating to the start of postwar filmmaking in New York, low-budget, independently financed features provided an invaluable avenue for city-bred talent, including New York University film graduates Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Susan Seidelman, Ang Lee, Jim Jarmusch, Darnell Martin, Peter Smollett, and Eva Vives. Alert to alternative ways of making films—from Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave to pioneering cinema-verité documentaries made in and around New York—these indie filmmakers recognized that the city itself could serve as an inexpensive yet visually compelling set. Transcending their tight budgets, independent filmmakers ingeniously transformed a wide range of urban locations into filmic settings and employed a diverse range of New Yorkers—in front of and behind the camera—to realize their visions.

Top

City Island

Philip Caruso, 2009

Reproduction

Photo by www.philipcaruso.net

For a story inspired by his own family in the Bronx, writer and director Raymond De Felitta found independent financing to work in the self-contained northern Bronx community of the title. Here a modestly sized crew films Julianna Margulies and the rest of the cast in a backyard overlooking the Long Island Sound.

Left

The Last Days of Disco

Whit Stillman, 1998

Reproduction

Courtesy of Everett Collection

To film his elegiac portrait of early 1980s New York, The Last Days of Disco, the independent filmmaker Whit Stillman brought cast, crew, and cameras into the confines of an actual subway car. In this view, Stillman (at right) and his crew review footage on a video playback monitor, one of the key technical innovations that made location shooting a practical alternative to soundstages.

Middle

Salesman

Bruce Davidson, 1969

Reproduction

Courtesy of the Associated Press

David and Albert Maysles filming a documentary in Manhattan. In the early 1960s New York filmmakers including the Maysles, Robert Drew, Ricky Leacock, and D.A. Pennebaker, pioneered ways to synchronize sound recording to lightweight 16mm cameras, allowing them to capture scenes of daily life almost anywhere. Their free-ranging documentary style—known as cinema-verité—soon exerted a profound influence on the city’s independent filmmakers.

Right

One People

Ali Santana, 2007

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Combining documentary-style footage with a fictional story of two sisters on a search for the contemporary relevance of the Black playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the short film One People was shot largely on the streets of Harlem, where in this view the director Alfred Santana (at right) oversees a modest crew.

LOCATION AS SPECTACLE

Ever since feature films began shooting on location in New York in the late 1940s, crowds of curious onlookers have themselves provided a compelling urban spectacle. The gathering of New Yorkers at locations for The Naked City in 1947 proved an irresistible subject for the young LOOK magazine photographer Stanley Kubrick (who was also observing the filming process for his own later career as a director). Where location shoots were once happened upon accidentally or by local word-of-mouth, in recent years websites and social media have drawn fans and paparazzi from around the city to high-profile shoots—a new kind of New York tourist attraction that is also an integral part of the city’s media machinery and culture of celebrity.

Top

Sex and the City: The Movie

Craig Blankenhorn, 2008

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

For the feature-film version of the popular New York-based television series, hundreds of onlookers—alerted by social media and websites— fill both sides of Fifth Avenue to watch Sarah Jessica Parker in bridal attire ascend the steps of the New York Public Library.

Left

The Lost Weekend

Unknown photographer, 1945

Reproduction

Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

In early October 1945, New Yorkers witnessed the first studio location scene shot in the city in nearly two decades: an alcoholic writer (Ray Milland) staggering down Third Avenue to find a pawnshop to sell his typewriter for drink money—unaware that all the shops have closed for Yom Kippur.

Middle and Right

The Naked City

Stanley Kubrick, 1948

Reproduction

Museum of the City of New York. The LOOK Collection. Gift of Cowles Magazines, Inc., X2011.4.10262.22, X2011.4.10262.34

The summer-long location shooting of Jules Dassin’s pioneering film drew thousands of New Yorkers—a spectacle in themselves. For LOOK magazine a young Stanley Kubrick captured portraits of New Yorkers watching the climactic chase on Delancey Street on the Lower East Side.

ACTION IN THE STREETS

Since the birth of modern location shooting in the 1940s, filmmakers have taken advantage of the extraordinary urban landscape of New York, whose busy streets, towering skyscrapers, elevated and underground subway lines, and soaring suspension bridges offer a dynamic, three-dimensional setting like few others in the world. Over the decades, ever more ambitious action scenes—including stunts, chases, and flying sequences that were once the near-exclusive province of studio lot—have been carried out on location in New York, aided in recent years by sophisticated digital techniques that can clean up filmed sequences in post-production to make them appear entirely realistic.

Top

The Amazing Spider-Man

Niko Tavernise, 2012

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

To stage a spectacular fight scene in the Marvel-produced sequel, filmmakers received permission from the Mayor’s Office to close Park Avenue for a Sunday morning location shoot.

Above Far Right

Fourteen Hours

Unknown photographer, 1951

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

Based on a real-life 1938 incident, the film focused on a disturbed man (Richard Basehart) threatening to jump from a hotel window ledge, photographed with a stunt double on the face of an actual office building at 140 Broadway.

Above Left

The Other Guys

Macall Polay, 2010

Reproduction

© 2010 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Courtesy of Columbia Pictures

Two stuntmen (doubles for detectives played by Samuel L. Jackson and Dwayne Johnson) jump from a building at Broadway and 25th Street, using harness wires erased in postproduction.

Above Right

The French Connection

Unknown photographer, 1971

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

In one of the most celebrated film chases in history, NYPD detective “Popeye” Doyle (Gene Hackman) careens up Brooklyn’s 86th Street pursuing the subway train above.

Above Far Right

The Cowboy Way

Barry Wetcher, 1994

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

In a climactic chase scene filmed on the Manhattan Bridge, stuntman Troy Gilbert (standing in for cowboy Woody Harrelson) leaps from galloping horse to subway car.

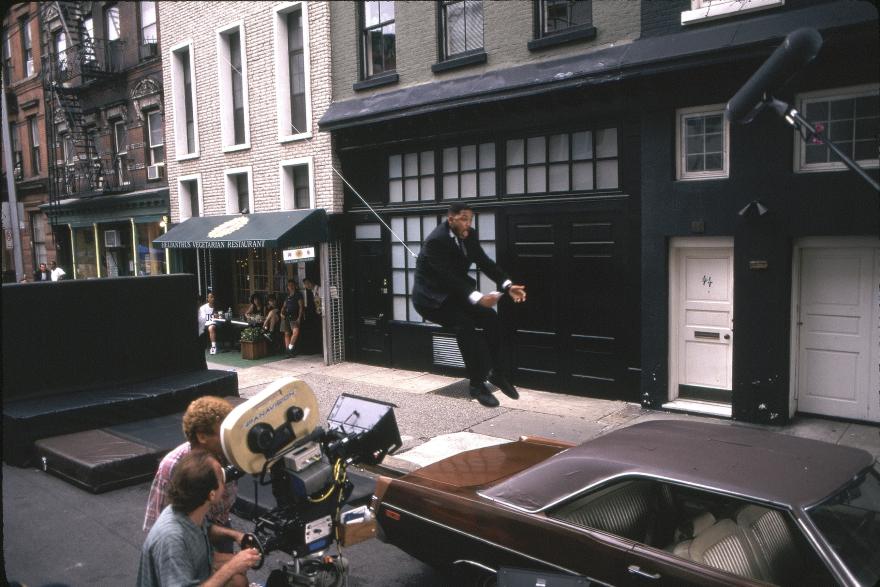

Below Left

Men in Black

Andrew Schwartz, 1997

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

On MacDougal Street in SoHo, Will Smith, as Agent J, is sent flying backward by the recoil of an alien gun. The actor was pulled by a winched cable attached to a harness under his suit—later digitally removed—toward a safety mattress to cushion his fall.

Below Right

The Joker

Niko Tavernise, 2019

Reproduction

Courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Playing a failed comic and clown, Joaquin Phoenix stands atop a step-street connecting Shakespeare and Anderson Avenues at the foot of 167th Street in the Bronx (now popularly known as “the Joker Stairs”), preparing to film the descent sequence that embodies his transformation into a psychopathic villain.

"THE STREETS WERE MADE OF MUSIC”

In 1949 the pioneering efforts of On the Tow n, using breakthroughs in playback technology and logistics, demonstrated that complex song-and-dance routines could be filmed outdoors on city streets. The effect was to turn New York into the grandest possible stage for musical numbers. For decades since, the city’s public spaces have come alive with performances large and small, from the unstructured energy of Fame or Blue in the Face to the precise choreography of West Side Story or In the Heights—whose main character, Usnavi (Anthony Ramos) tells us that in New York, “the streets were made of music.”

Top

West Side Story

Niko Tavernise, 2021

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

For their remake of the original 1961 film, Steven Spielberg and his production team, unable to find suitable late-1950s period locations in the West 60s blocks of Manhattan—long since demolished for Lincoln Center—transformed the Harlem intersection of 113th Street and St. Nicolas Avenue into the setting for the film’s exuberant “America” dance number.

Left

Fame

Holly Bower and Catharine Bushnell, 1980

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

As startled Midtown office workers look on, actors playing students from the High School of Performing Arts spill out onto West 46th Street, bringing traffic to a halt with an impromptu music and dance number.

Middle

Blue in the Face

K.C. Bailey, 1995

Reproduction

Courtesy of Photofest

A quasi-improvised feature by writer Paul Auster and director Wayne Wang, the film includes an impromptu neighborhood dance led by RuPaul on a corner in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn.

Right

In the Heights

Macall Polay, 2021

Reproduction

Courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

In bringing Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit musical to the screen, director John M. Chu used a highly mobile camera and digital effects to transform the streets and open spaces of the city into a magical realist setting for large-scale music and dance numbers. In this image the filmmakers are staging an elaborate sequence with Melissa Barrera on Astor Place in Manhattan’s East Village.