“Madame” Demorest—The Woman at the Top of a 19-Century Fashion Empire

Wednesday, April 15, 2020 by

In the Museum’s exhibition New York at Its Core, visitors can virtually “meet” New Yorkers from the city’s past, including those who contributed to the industries that still define the city’s reputation today. One of those New Yorkers is Ellen Curtis “Madame” Demorest, a pioneering and creative New York entrepreneur, who, with her husband William, created a massive fashion empire in New York City in the middle of the 19th century. It was an empire built on two burgeoning industries in New York City—magazine publishing and fashion. And it rested on an innovation that played on the aspirations of middle-class women who wanted to look like the stylish upper-class women of the fashion capitals of Paris, London, and New York City itself, giving them the tools to literally refashion themselves.

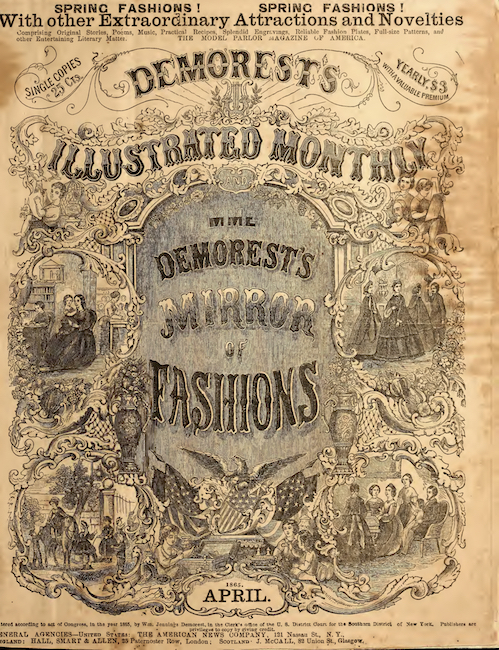

In many ways, reading a fashion magazine in the mid-19th century wasn’t that different from reading one today—the pages are full of beautiful clothes, helpful advice, and interesting stories. One of the most popular magazines of the 1860s was Demorest’s Illustrated Monthly and Mme. Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions. Calling itself “The Model Magazine of America” it also boasted “Splendid Engravings, Original Music, Mammoth Fashion Plates, Entertaining Poems & Stories, Valuable Recipes, Full Size Fashionable Patterns & Other Valuable Novelties.”

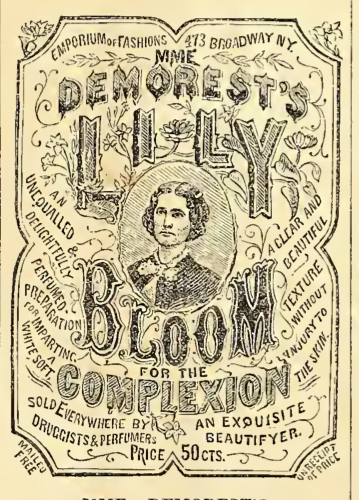

And, just like today, considerable space was given over to paid advertisements (allowing publishers to lower the price of the magazine and increase circulation). At the back of an 1865 copy of Mme. Demorest’s Mirror of Fashion, sprinkled in with advertisements for Tiffany & Co., Steinway & Sons pianos, and several different home sewing machines, are also advertisements for “Mme. Demorest’s Lilly Bloom for the Complexion,” “Mme. Demorest’s Everlasting Perfume,” “Mme. Demorest’s Superior French Corsets,” Mme. Demorest’s Sewing Ripper,” and even, “Mme. Demorest’s Spiral Spring Bosom Pads,” for “those who require some artificial expansion to give rotundity to the form.” It was no mistake that the Madame’s products were advertised in the pages of her very own magazine. It was, in fact, the point.

When the Demorests opened their first shop, Madame Demorest’s Emporium of Fashions, on lower Broadway in 1860, New York’s reputation for elegance and style in women’s fashion was already well established. Just ten years earlier, in his American Notes Charles Dickens remarked, “Heaven save the ladies, how they dress! We have seen more colors in these ten minutes, than we should have seen elsewhere in as many days. What various parasols! What rainbow silks and satins! What pinking of thin stockings, and pinching of thin shoes, and fluttering of ribbons and silk tassels, and display of rich cloaks with gaudy hoods and linings!”

By the 1870s the Demorests’ Fashion Emporium was located at 17 East 14th Street between Fifth Avenue and Broadway—at the heart of a district that became known as “Ladies’ Mile.” Up Broadway at 20th Street was the department store Lord & Taylor (then at its second location), farther down Broadway, at the 10th Street, was A.T. Stewart’s Cast Iron Palace, and Siegel Cooper was up on 18th Street and Sixth Avenue. The relatively new activity of “shopping” was becoming an acceptable way for well-dressed women to stroll, unchaperoned, along the streets of Ladies’ Mile, seeing and being seen.

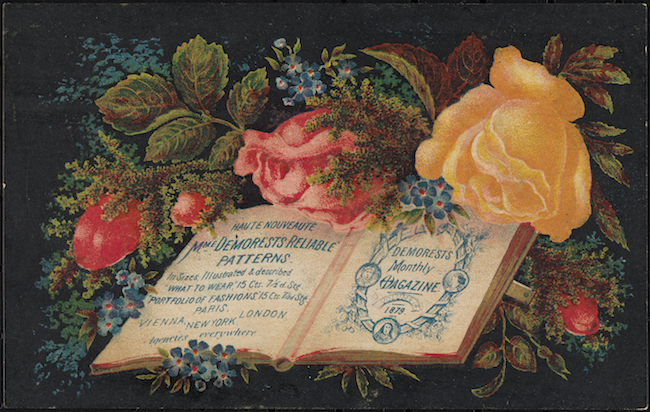

These same styles seen on the streets of Ladies’ Mile could also be found in beautifully detailed, often hand-colored fashion plates in magazines published by Ellen and William Demorest. The couple eventually published five separate periodicals, reaching a combined circulation of over one million. The flagship publication, Mme. Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions, started in 1860 as a quarterly magazine. By 1865 it was monthly and called Demorest’s Illustrated Monthly and Mme. Demorest’s Mirror of Fashion; eventually it became simply Demorest’s Monthly Magazine. The couple’s other publications included titles like Mme. Demorest’s What to Wear and How to Make it.

But, Ellen Demorest’s true innovation, hinted at in the title of that last magazine, was not her store, nor her magazines. Instead, it was her dress patterns—she was the first to successfully mass produce, market, and sell paper dress patterns directly to consumers. The patterns were included as foldouts inside the magazines as well as sold on their own, by the Demorests themselves, or through agents. The success of the pattern business was built on the increasing availability of home sewing machines, and the promise that home sewers, or small-time dressmakers, could make their own copies of the fashions normally out of reach of all but the wealthiest women.

The patterns also extended the couple’s reach—agents selling patterns could be found other in American cities, where local dressmakers, as well as home sewers, used their patterns to produce the latest styles. In their own hyperbolic language, “Mme. Demorest’s Reliable Patterns, in illustrated envelopes, have become a necessity, and scattered broadcast through the medium of a thousand agencies, are within the reach of every one, at a merely nominal price, wherever civilization extends.” One advertisement even bragged, “so general is their use that, besides English and French, the directions are printed in Dutch, Portuguese, German, and Spanish.” Demorest’s patterns were so innovative that they won several prizes at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. That year, the Demorests distributed three million patterns through 1,500 agencies.

The Emporium, magazines, and dress patterns made up a three-pronged strategy aimed at a new kind of consumer. The text of an 1878 issue of Mme Demorest’s What to Wear and How to Make It (published by J.J. Little, where William Demorest was a partner), gives us a clue as to who Madame Demorest thought her customers were. An article titled “Notes on Ocean Travel” begins, “The Paris Exposition will undoubtedly attract large numbers of people from all quarters of the globe, and those of our readers who are anticipating, with mingled feelings, their first passage across the Atlantic will doubtless be grateful for some information about those numberless details, which, if properly attended to, will conduce so much to their comfort.” It goes on to give practical advice on how to choose a steamer, when to book a ticket, and what baggage to carry, but also, of course, descriptions and illustrations of the dresses her reader should bring—“Traveling dresses should be short,” the text reads, “and new.” She thought of her customers as women who had just enough disposable income and leisure time to travel to Europe, not frequently, but for the very first time for a very special occasion. Or at least, women who thought of themselves as the kind of women who could.

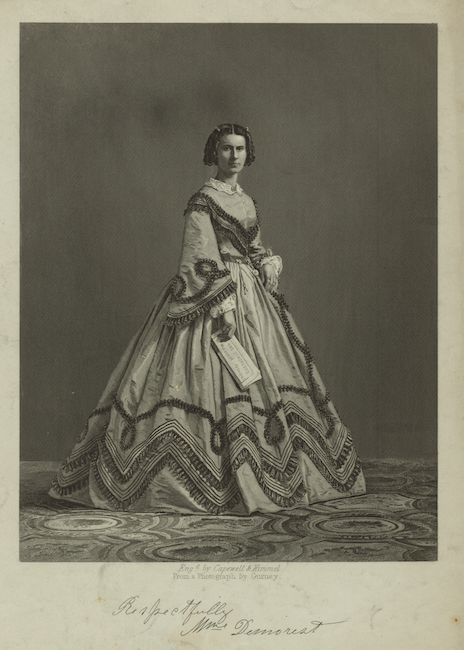

Demorest may also have had in mind a strong-willed woman somewhat like herself. Ellen Curtis was born in Schuylerville, New York, near Saratoga Springs, a summer destination for the fashionable leisure class since the 1820s. Saratoga was described in an 1865 edition of Demorest’s Monthly Magazine, as a place where “for a few weeks or months, these ordinary dull and commonplace villages and hamlets…present the spectacle of a grand reunion of wealth, fashion, and beauty out of doors.” At 18, with the help of her father who owned a men’s hat factory, she opened a successful hat shop there. By the time she met and married William Jennings Demorest, a widower who owned a dry-goods shop in New York City, she was 34, an unconventional age to be married for the first time. “Parents,” she once said, “teach your daughters some remunerative business. Select for them as you do for your sons.”

In later years, she prided herself on being both a business owner and an employer of women, including African-American women, whom she treated as equals among her staff. Her views on this subject were so strong that she once got into a heated, days-long debate in the Letters to the Editor section of The New York Times on the subject of “Women’s Work and Wages.” She began her first letter with the biting words: “Inasmuch as you are not a woman, and do not, to any extent, employ women, allow one who is, and does, to reply…”

Demorest’s independent spirit could be seen in her magazine as well. In addition to reporting on the latest fashions, she published writing by Louisa May Alcott, Julia Ward Howe, and the journalist Jane Cunningham Croly, who wrote under the pseudonym Jennie June from the magazines’ beginnings in 1860 through 1887. Croly, an interesting figure in her own right, used her columns to champion women’s accomplishments and causes.

In 1868 Demorest joined Croly in founding the first professional women’s club in New York, called Sorosis, in response to Croly’s frustration at being shut out of an all-male reception given by the New York Press Club for Charles Dickens. The following year, Sorosis held a tea for that very Press Club at Delmonico's, which was, according to Demorest’s Monthly Magazine “unique in the annals of entertainments, the ladies paying the bills, and making the speeches in response to the toasts, while the gentlemen sat still and looked on.”

When Demorest stood to speak, she made a case for the right of women to speak in their own voices, “We charge” she said, “that man as monopolized the right to declaim, lecture, preach, or speak in all forms known as public speaking.” Her speech (as reprinted in Demorest’s Monthly Magazine) also managed to sum up her philosophy. She outlined the ways in which women’s lives were circumscribed by their relationships to men: fathers, and then husbands who have, “claimed the monopoly of all money, personal property, &c. that marriage professedly makes of joint ownership,” before concluding, in words as provocative as they were self-serving: “why wonder that she learns to smile at suggestions of extravagance in dress, and adds another yard to her train, or buys a more expensive set of lace for the next party, and sprinkles gold-dust over her glossy hair? She is none the poorer for the outlay, for ordinarily a wife owns only her own wardrobe.” Indeed, it was that outlay that made Ellen Demorest a successful businesswoman, at a time when that distinction was rare.