The Photographs of Robert Rauschenberg

Reflecting on the artist's lifelong relationship with photography and New York City

Thursday, November 6, 2025

As part of Robert Rauschenberg’s New York: Pictures from the Real World, organized in honor of the artist’s centennial, Senior Curator of Prints and Photographs Sean Corcoran reflects on Rauschenberg’s lifelong relationship with photography and New York City. The exhibition is on view at the Museum of the City of New York through April 19, 2026.

Throughout his career, how did Robert Rauschenberg’s photography influence his larger artistic practice?

Sean Corcoran: Photography was integral to Rauschenberg’s creative process from the very beginning. Soon after he began taking his own photographs in the late 1940s, he started incorporating them (alongside found and appropriated images) into new works of art. This approach culminated most famously in his Combines (1954–64), where he brought together his own photographs, photographic reproductions, newsprint, and found objects within his paintings.

In the first section of the show, we see some notable people featured in a few of Rauschenberg’s photos. Can you tell us a bit about one of them and who they were in terms of their connection to Rauschenberg?

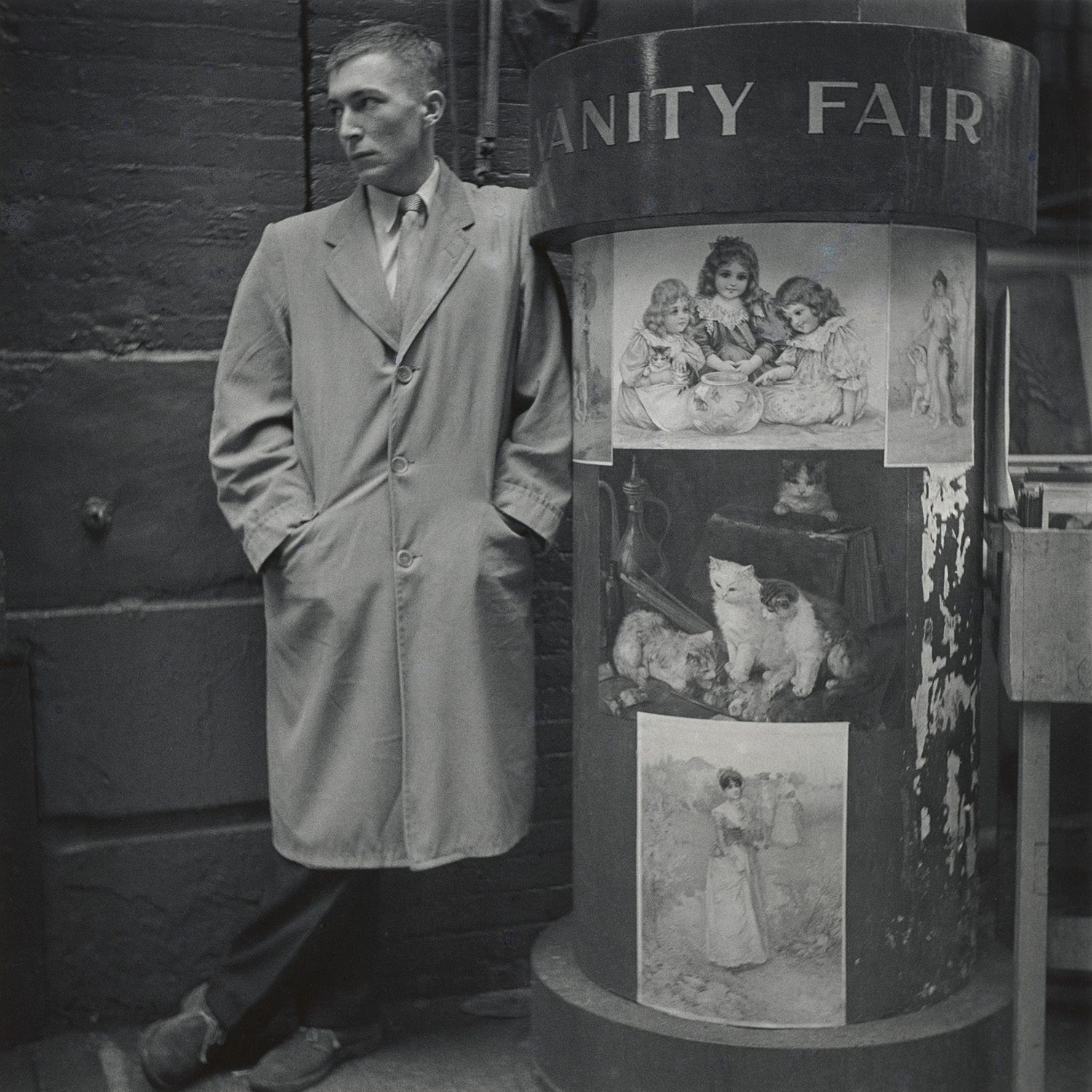

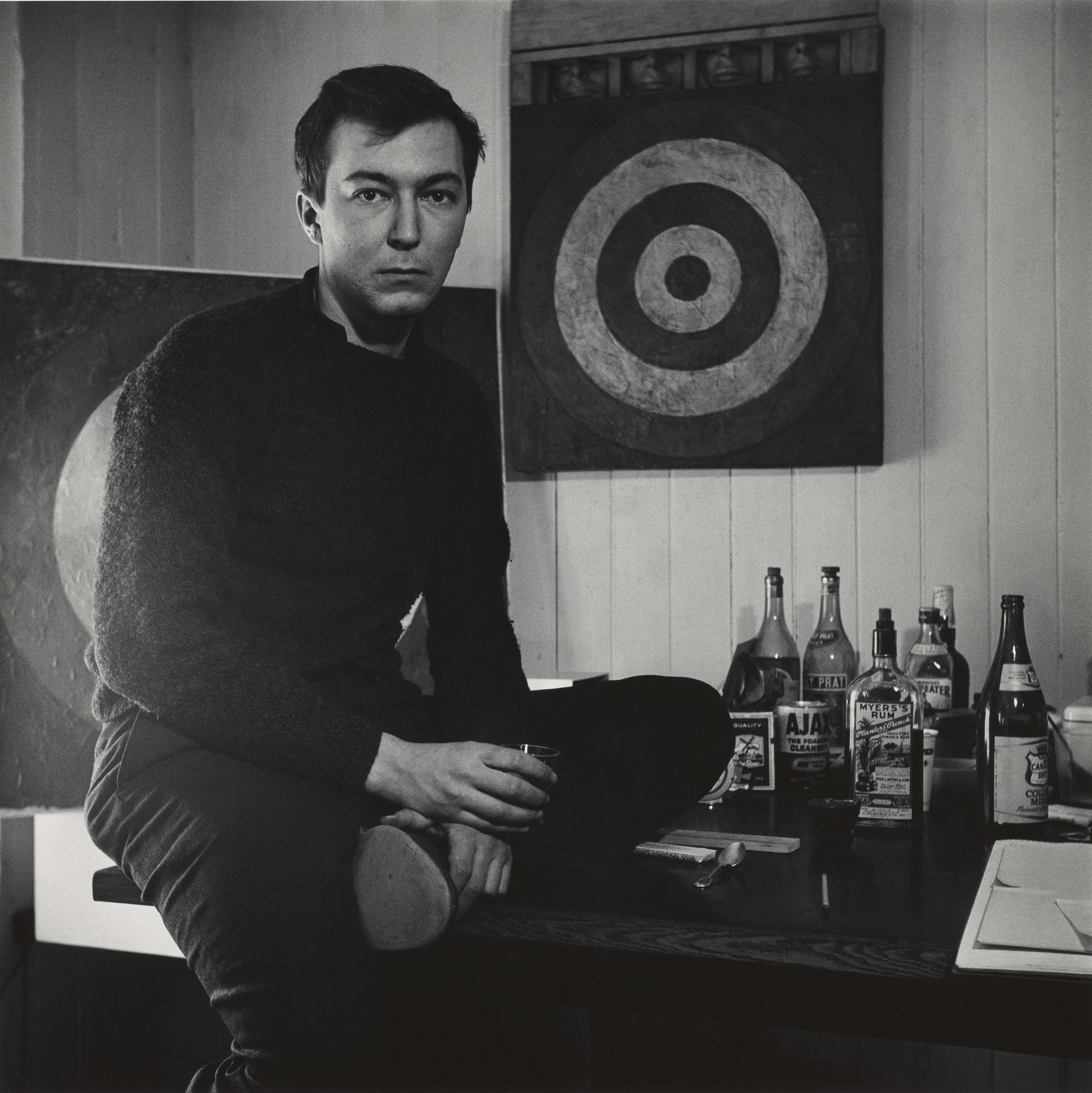

Sean Corcoran: One of the most significant figures we see is artist Jasper Johns. Rauschenberg met Johns in late 1953, and they soon began an intellectual and romantic relationship that lasted until 1961. The portrait of Johns included here was taken in 1958, shortly after the two relocated to 128 Front Street in the South Street Seaport district, where they maintained studios on adjacent floors.

This was an extraordinarily productive period for both artists. Rauschenberg was creating and exhibiting his Combines while also collaborating with the Merce Cunningham and Paul Taylor Dance Companies. At the same time, Johns had just held his first solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery. In the background of Rauschenberg’s photograph, we can see two of the works from that show: Target with Four Faces (1955) and Target (1958).

Rauschenberg eventually stopped taking his own photographs for a time. What led to that, and how did it affect his work?

Sean Corcoran: In the 1960s, Rauschenberg lost his camera, and for many years afterward he largely stopped making his own photographs. We’ve included in this exhibition a silkscreen painting—Untitled (1963)—that demonstrates how, even then, photography remained central to his practice. The work combines imagery from his own photographs of the Merce Cunningham dancers with images he gathered from other sources, showing how he continued to explore photographic imagery through other mediums.

When did he return to photography, and how did his approach evolve in that later period?

Sean Corcoran: Rauschenberg returned to taking photographs in 1979. These later images often stood on their own as artworks, but they also served as source material for his work in other mediums. He experimented with recontextualizing his photographs—altering their size or color, reversing them, or layering multiple images. This process underscores the fluidity of photography and how its meaning can shift through manipulation and reinterpretation.

What kinds of works from this later period are included in the exhibition?

Sean Corcoran: The other artworks on view in this gallery were created between 1981 and 1994. They feature imagery drawn from Rauschenberg’s later photographs made in New York City, showing how his engagement with photography continued to evolve throughout his career.

![Leland Bobbé, Subway [Voice of the Ghetto], 1974. Archival pigment print. Gift of the photographer. 2016.10.7.](https://www.mcny.org/sites/default/files/styles/mcny_col_3_thumbnail/public/mn185974_0.jpg?itok=8q3-MZ35)