Juan Rodriguez

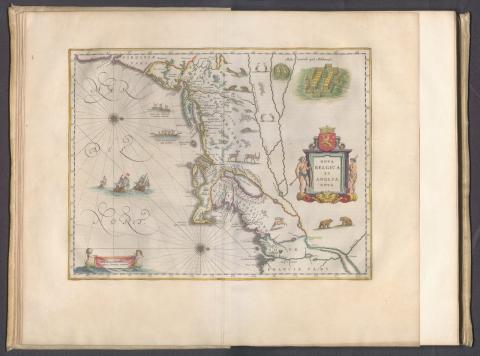

Juan Rodriguez (in Dutch: Jan Rodrigues) was a Black or mulatto (mixed race) man who traveled in 1613 to Manhattan from Santo Domingo (today’s Dominican Republic) in the Caribbean aboard a Dutch merchant ship called Jonge Tobias. The ship’s crew most likely traveled to the East Coast of North America to make contact with Natives peoples with whom they could trade and search for valuable raw materials of the region. When the European crew return to the Netherlands, Rodriguez stayed behind, against the captain’s wishes.1 He received his wages in trade goods that would have been both useful to Rodriguez’s survival and highly valued among the Munsee: “eighty hatchets, some knives, a musket and a sabre.”2 Perhaps he recognized that he would have more control over his life on Manhattan Island than as a member of a European ship crew. When Dutch ships returned the following year, Rodriguez was still there.

We cannot say with certainty what Rodriguez did during that year living in the region the Dutch would eventually call “New Amsterdam,” but it is fair to assume that he would have spent much of his time building relationships with and learning how to live in this new environment from the region’s Munsee inhabitants. When the Dutch ship (The Fortuyn) arrived in Manhattan the following year, the captain likely hired Rodriguez to help establish trading relationships with Munsees. Rodriguez thus served as a kind of cultural middleman between the Europeans and Indigenous peoples. But soon after this, Rodriguez’s former captain returned to the island and was displeased to find him aiding a competing ship’s crew. Rodriguez maintained that he was a free man, and could work for whom he wished. A fight broke out between Rodriguez and his former shipmates Unfortunately, this is all that we know of Rodriguez’s life in New Amsterdam from first-hand sources. It does seem likely, though, that Rodriguez lived out the rest of his days as the first non-Indigenous resident on the land known today as New York City.3

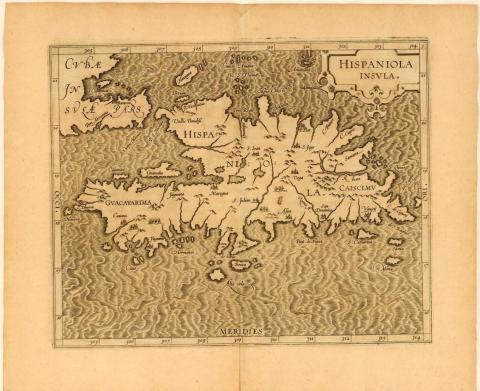

Rodriguez represents a larger group of people of African ancestry who traveled the Atlantic world, becoming fluent in its many languages, economic systems, and cultures, which the historian Ira Berlin termed “Atlantic Creoles.”4 For his own part, Rodriguez would have developed his “Creole” identity within the unique cultural setting of late sixteenth-century La Española, or Santo Domingo.The island’s Indigenous Taino population had shrunk due to diseases, starvation, and being forced to labor in silver mines by Spanish colonizers during the first two decades of occupation (c. 1492-1508). In response, the Spanish began importing enslaved Africans. By the time Rodriguez left for New Amsterdam in 1613, La Española’s population had consisted of a majority of people of African descent for over fifty years. While Spanish imperial officials tried to control La Española’s trade, a vibrant smuggling economy developed, where residents like Rodriguez would have become used to defying colonial authorities to trade with other empires (like the English, French, or Dutch) for their own gain.5 Perhaps these practices led Rodriguez to be more willing and accustomed to working across cultural and political boundaries in order to best suit his own needs once he arrived in New Amsterdam.

Rodriguez likely became fluent in Munsee, Dutch, and Spanish, developed relationships with both Indigenous sachems and European captains, and learned how to navigate both European and Native cultures alike. By doing so, he would have positioned himself as an ideal negotiator to help build relationships between Europeans eager to trade, and Native peoples who not only had access to in-demand goods, but whose knowledge of the landscape would have been vital for European traders and would-be-colonists. In other words, by becoming familiar with a variety of languages and cultural practices, Rodriquez made himself particularly valuable to both Native sachems and European ship captains.6

Rodriguez’s story helps to remind us that the history of African-descended peoples in the Atlantic world cannot be reduced or limited to the experience of enslavement. Rodriguez’s ability to build relationships across cultural and political boundaries probably stemmed from his identity as an “Atlantic Creole” of African descent who grew up on La Española in the late sixteenth -century. Furthermore, the extent to which Europeans relied upon Rodriguez to mediate their relationships with Indigenous peoples also helps to highlight the fact that European power–especially in the earliest decades of interaction with Munsees–remained relatively weak on Manhattan Island and its surrounding landscape. At the same time, the bitter feelings Rodriguez spurred when his former crew found him working for a different captain demonstrates the fierce competition among European merchants over resources and trade networks during an age of expanding Atlantic commerce and European colonization. In New Amsterdam, this competition ultimately disappeared amongst Dutch traders when the States General, the highest governing authority in the Netherlands, agreed to place the regulation of New Amsterdam and, more broadly, New Netherland, under the newly-formed West India Company in 1621.7

Footnotes:

1. Anthony Stevens-Acevedo, Tom Weterings, and Leonor Alvarez Francés eds., “Juan Rodriguez and the Beginnings of New York City,” Published for the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute (CUNY Academic Works, 2013), 2; Jaap Jacobs, New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America (Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishing, 2004), 13. See also Simon Hart, The Prehistory of the New Netherland Company: Amsterdam Notarial Records of the First Dutch Voyages to the Hudson (Amsterdam: City of Amsterdam Press, 1959).

2. Stevens-Acevedo, Weterings, and Francés eds., “Juan Rodriguez,” (2013), 22.

3. Stevens-Acevedo, Weterings, and Francés eds., “Juan Rodriguez,” (2013), 2.

4. Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, MA: The Belnkap Press, 1998), 17.

5. Stevens-Acevedo, Weterings, and Francés eds., “Juan Rodriguez,” (2013), 9-10.

6. Andrew Lipman, The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), 97-98.

7. Lipman, The Saltwater Frontier (2015), 98-99.

Supporters

The People of New Amsterdam project is supported as part of the Dutch Culture USA program by the Consulate General of the Netherlands in New York.

The Frederick A.O. Schwarz Education Center is endowed by grants from The Thompson Family Foundation Fund, the F.A.O. Schwarz Family Foundation, the William Randolph Hearst Endowment, and other generous donors.