Cornelis Steenwijk

As New Amsterdam grew from a humble trading post to a more established village, successful Dutch merchants like Cornelis Steenwijk (1626-1681) used the colony’s economic opportunities in order to secure social and political status in the new world. Born in Haarlem in the Netherlands, Steenwijk worked as a representative for a major Amsterdam trading house, one of four large companies that dominated the trade between the Dutch Republic in Europe and the growing New Netherland colony in North America.

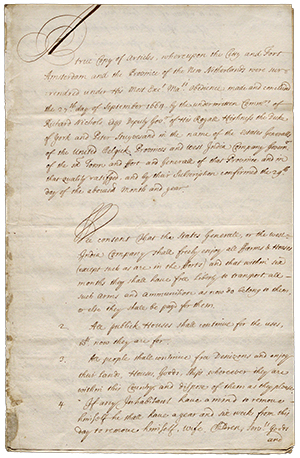

When fighting broke out again between Spain and the Netherlands in 1621 after a twelve-year-long truce, the States General - the Dutch Republic’s highest legislative body - created a new, state-sponsored trading company called the West India Company to oversee and regulate all trade between the Dutch Republic and the Atlantic colonies.

But in the late 1630’s, in order to increase the number of raw materials the Netherlands could import from its colonies, the States General began to pressure the Company to give up its monopolies on some of New Netherland’s trading sectors (the largest were fur, skins, tobacco, and timber). When the WIC finally gave in, the Company began by opening up the fur trade to private merchants which allowed them to have more impact in the colony’s economy, while building their own wealth and influence.

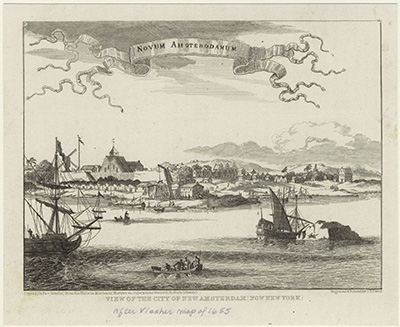

There is not much known about Steenwijk’s life, but with careful study of the available documents, historians have made a number of inferences. Steenwijk probably arrived in New Amsterdam around 1651, just in time for Petrus Stuyvesant, then director (or governor) of the New Netherland colony, and the States General to approve the creation of a civil government, allowing local property-owning men of some wealth to participate in the town’s daily governance. This excluded a great number of colonists who could not hold power in local government, including all women and men who did not own property.

Within a few years of his arrival, Steenwijk probably moved into a house at present day No. 27 Pearl Street, next to the WIC doctor Hans Kierstede and his wife Sarah, and used the bottom floor of his home as a shop. He quickly built himself into a prominent merchant-trader working in both foreign and domestic markets. This would include exporting raw materials like wood and animal furs to and importing goods from Europe like duffel cloth, pipe stems, liquor, and gunpowder.

By 1653, Steenwijk had become one of New Amsterdam’s wealthier residents. A document from that year shows Steenwijk had loaned a large sum of money to the New Amsterdam government in order to fund repairs to Fort Amsterdam and the construction of the wall that ran down the length of present-day Wall Street. While Steenwijk was successful in his import and export business of raw materials and goods, it is important to recognize that part of Steenwijk’s wealth came from his involvement in the expanding trade in enslaved Africans. Traders had brought enslaved Africans to New Netherland as early as 1624.

By the late 1650’s however, New Amsterdam’s director Petrus Stuyvesant worked with the West India Company to dramatically increase the number of enslaved peoples imported to New Amsterdam each year. Steenwijk purchased two ships of his own in 1662 to make trips to Curaçao, then a Dutch colony in the Caribbean, and the Chesapeake, both major stops in the Atlantic slave trade.

By exporting local raw materials and importing European-made goods and enslaved Africans, Steenwijk secured a level of influence that would have been closed off to him back home in the Netherlands, where the population by this point tended to be more rigid in terms of social mobility with the widening gap between the wealthy and working-class populations. Steenwijk was eventually appointed burgemeester, local magistrate or civil officer, in 1664. While he only served a single term before New Amsterdam fell to the English, Steenwijk also held a number of administrative positions under English Rule, including the relatively new office of Mayor of New York, as the English renamed the town.

Not only did Steenwijk establish himself as a merchant in New Amsterdam, but he built a life for himself there. In 1658, Steenwijk married Margaretha de Riemer, with whom he had seven children. By the early 1670’s, records show that Steenwijk was still one of Manhattan’s wealthiest residents. He funded the construction of a lavish house on the corner of Bridge and Whitehall streets, complete with chairs made from Russian leather, paintings by Dutch Masters, French cabinets, and statuary.

Ultimately, Steenwijk’s life illustrates the kinds of social mobility New Netherland offered to Dutch merchants. While men like Steenwijk rose through New Netherland's economic classes and dominated the town’s government, other residents of the colony, including poor Dutch and European laborers as well as free and enslaved Africans, struggled to gain access to the same kinds of privileges that could propel them into the ranks of the colony's elite.