Sara Kierstede

Sara Kierstede

Sara Roeloffs was born in Amsterdam in 1627 to Scandinavian immigrant parents. Over her very long life, she would marry three times, and is known today mostly by the last name she used during her first (and longest) marriage: Sara Roeloffs Kierstede. Her father, Roeloff Jansz van Marstrand (aka Maesterland), was a sailor who had probably moved to Holland in search of work.1 At the time, Amsterdam was a wealthy port city, filled with merchants who made their living by trading bulk goods like grain, wood, salt, and fish and luxury items like spices, sugar, dyes, and silk, as well as artisans who turned trade goods and raw materials into consumer products like finished clothing.2

Sara, her sister Trijntjen, and her parents moved to New Netherland in 1630, joined at some point by her grandmother and aunt, as well. They planned to work as farmers for the newly established Rensselaerswijk, a large rural estate, or patroonship, founded by the Dutch diamond merchant and West India Company director, Kiliaen van Rensselaer. The estate was located along the Hudson River, near present-day Albany. Sara’s father worked as a tenant farmer, meaning that the family worked for pay, alongside two hired hands, on land owned by the Van Rensselaers.3 Life for a farm family in the early days of the colony would have been difficult, with long hours tending to crops–especially wheat and rye–and livestock such as pigs, sheep, and cows.4

Eventually, her father, Roeloff, rose to become a member of the patroonship’s governing council. But soon, the family moved to Manhattan to work as farmers for the West India Company. Shortly, they received title to some sixty-five acres of land of their own, entering the higher social class of free farmers. Roeloff, however, died not long thereafter, leaving a widow and five children, with Sara, the eldest, just nine or ten years old. 5

SK-C-113.]

Sara’s mother, Anneke Jans, ensured that her children would continue to rise through the colony’s social ranks when she remarried. She selected as her new husband the New Amsterdam minister, Everardus Bogardus. Sara’s own marriage to the West India Company surgeon Hans Kierstede in 1642 signaled her entry into the small colony’s uppermost ranks, comprised of wealthy merchants and officers of the WIC. Sara’s sisters and her aunt also married into the colony’s higher echelons. Even her grandmother enjoyed a position of influence and respect, working for the Company as a midwife. Though left fatherless as a child, Sara and her sisters lived among the colony’s elite from a young age.6

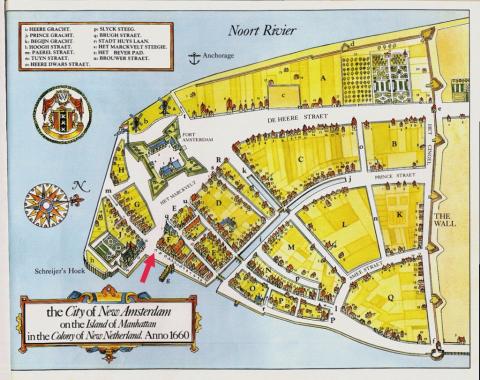

Sara’s marriage to Hans Kierstede took place when she was only fifteen years old, much earlier than young people tended to marry in the Netherlands at the time. Her age at marriage serves as a reminder of the pressure that female settlers faced to wed at a time when white men continued to outnumber white women; her husband was some ten years her senior. Her first son, Hans, was baptized in the Dutch Reformed church just two years later. The couple would go on to have nine more children together, two of whom died young. Like other members of Dutch society, Sara and Hans expanded their family ties by asking important New Amsterdammers to serve as godparents to their many children. Director Willem Kieft, acting governor of New Netherland, was one of the many town residents who agreed to be a godfather to one of their babies.7 Sara and Hans, too, served as godparents to others, creating connections who their children could call on if they ever needed help. The family lived by the shore in New Amsterdam, on Pearl Street. By the time she became an adult, Sara would have been living a comfortable if busy life surrounded by family and kin.

Yet Sara is best known for something quite different: she worked as a translator in negotiations with Manhattan’s and the Hudson Valley’s original inhabitants, especially Munsee-speaking peoples, including the Lenape. She interpreted at wartime talks, served as a conduit for news from Native visitors to the colony’s leaders, and developed a particularly close relationship with one of the region’s most important Lenape-Munsee leaders, Oratam of Hackensacky. Such political activities, while not unknown for Native women, were highly unusual among Dutch women.

How had Sara learned to speak Munsee?8 Some have suggested that she learned to talk to Mahican children while living upriver as a girl.9 We will never know for certain, but she could also have learned Munsee in New Amsterdam as a young woman from Lenape women and men come to sell goods to colonists. Sara and Hans lived in a house just off New Amsterdam’s market square, where visitors from Lenape and other Native communities gathered each week to trade food and goods with the Dutch and other European residents. Part of Sara’s normal responsibilities as a Dutch “housewife,” or huysvrouw, would have included buying necessities for her family in that marketplace.10 The colony even erected a small house for Lenape and other Indigenous traders, making Sara one of their closest neighbors when they came to town. It is possible that she could have even learned Munsee at home; years later, as a very old woman, Sara referred in her will to “my Indian named Andries,” – if other Indigenous servants or slaves had lived in her households when she was younger, she could have learned the language from them.11 However she had first learned to speak Munsee, her life in the colonial town would have provided her with ample opportunity to keep her skills sharp.

Sara clearly learned the language well, acquiring the ability to talk about many things besides trade. As a surgeon, Hans needed to know about healing plants and herbs, and Sara seems to have helped him learn from Indigenous visitors what to plant in their medicinal garden.12 Seeds from goosefoot and wormseed, both used by Native American herbalists as astringents and anti-inflammatories, have been found by archaeologists in a Pearl Street site posited to be the remains of the Kierstede garden, along with other indigenous food and herb crops.13 Since there are no indications that Hans Kierstede could speak local languages, it must have been Sara who learned about these plants and their properties from Munsee-speakers. Descendants of Hans and Sara later spoke of her as the healer in the family.14 Growing up alongside her grandmother the midwife, and being a mother of a large brood herself, she could well have had interests in healing herbs for her own part, not just on behalf of her husband.

It is not clear when Sara began translating not just for her husband and family, but also for the colonial government itself. Yet over time, as tensions increased between Lenapes and land-hungry settlers, her language skills became so crucial that the records begin mentioning her by name. Beginning in May 1658, European colonists in the upper Hudson Valley lead a series of brutal attacks against a Lenape community known as Esopus that spiraled into vicious wars lasting six years. Amidst this situation, Dutch officials in New Amsterdam felt that it was critical to ensure peaceful relationships with other Munsee-speaking communities–especially those living on Long Island and the southern shores of the Hudson. Starting in July 1663, Sara is specifically named as translator for area sachems (political leaders) in a series of treaty negotiations. She interpreted for Sauwenaare, a sachem of Wiechquaeskeck, and Metsewackos, a sachem of Kichtawangh, during a conference at which the two leaders agreed to stay out of the fighting at Esopus, so long as Europeans stopped selling alcohol to Native peoples.15

However, it was the Hackensack sachem Oratam with whom Sara spent the most time. Sara translated Oratam’s words in July 1663, when he informed Dutch Director- General Petrus Stuyvesant that he had convinced most Lenape-Munsees to remain neutral in the fighting and to forebear coming to the aid of the Esopus militarily. Sara also poke for Oratam when he played a leading role halting hostilities between the Dutch and Esopus first in November 1663, and then at the final negotiations in July 1664.16 Ultimately, Sara would be well rewarded for her work, receiving land on Manhattan in the 1670s from the colonial government, and a huge parcel in what is now New Jersey from Oratam.17

Sara Roeloffs’s life also sheds light on the importance of slavery in New Amsterdam and New York and her direct involvement through her documented ownership of enslaved people. She would have witnessed Africans – sometimes in chains – doing heavy construction, farming, and dockside labor from the time she moved with her parents to Manhattan as a girl. Men and women from Angola and elsewhere in Central West Africa had arrived as the property of the West India Company beginning in the late 1620s. Enslaved women seem to have been expected to do housework, without pay, in the homes of elite colony leaders and ministers, men like her own stepfather, Everardus Bogardus. What is more, Bogardus had himself lived in Africa and took pains to include New Amsterdam’s free and enslaved Africans in the church congregation that he led. Sara likely saw numerous baptisms of African congregants firsthand, and her mother served as a godmother to a Black child on at least one occasion.18 Yet Sara’s final will, dated July 29, 1693, discusses in detail exactly which of her descendants would receive each of six enslaved people.19 Two “negro boy[s]” – Jan and Pieter – alongside two “little negro girl[s]” – Susanna and Maria – each went to different households. A “Negro woman named Sara,” almost certainly their mother, went to the same family as little Maria, while Sara bequeathed “my Indian named Andries” to yet a different descendant. Breaking up a young family to distribute enslaved children among relatives by will was a common strategy for elite men and women in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New York, who understood slave holding as a key marker of the upper class and wished to provide that prestige for as many of their offspring and heirs as possible.20

We will never know when Sara Roeloffs first began keeping Africans and Native Americans as her own personal property. Private slave ownership, as opposed to slaveholding by the West India Company, only expanded gradually in New Netherland, and it seems that very few Indigenous Americans found themselves enslaved in early New Amsterdam. Yet the fact that the one adult woman mentioned in the will was called “Sara” raises the possibility that she had been born into and grown up in Sara Roeloffs’s own home. Since holding war captives in slavery and exchanging those captives during diplomacy were common practices across the Native Northeast, Sara’s possession of Andries very well could have dated to the period of her translating work during the Esopus wars in the early 1660s. Her second husband, Cornelis van Borsum, who she married in 1669, was a member of the family that operated the ferry to Long Island, relying on enslaved Africans as ferrymen.21 Land that the couple received in 1673 as payment for her translating work soon came to be used as the African Burial Ground.22 Sara Roeloffs’s ties to the system of slavery and to Manhattan’s enslaved population ran deep, likely beginning decades before her death in the 1690s.

After Hans Kierstede died and she remarried Cornelis van Borsum, Sara had one more child, a daughter named Anna. Anna was an innocent, in Sara’s words – that is, developmentally disabled. Sara and Cornelis came to have extensive business interests in Esopus, the area cleared of Lenape families for white settlers during the very wars underway when Sara translated for the Dutch colony. After Van Borsum’s death, Sara married a third and final time to Elbert Elbertsz Stouthoff, outliving this last husband, too. Anna, though, lived with Sara for the rest of her mother’s life, in a “little house & kitchen” with a “lot belonging to it”. Sara probably still planted produce in that garden lot, though archaeologists suggest far fewer indigenous plants and herbs grew there by the end of her life.23 Sara operated a “bakehouse” next to her cottage, and her son, Lucas, occupied the big house she owned adjoining it.24

Sara’s story, and her relationship with Oratam, reveal a few crucial facts about life in New Amsterdam. It demonstrates the importance of personal networks for social mobility. Sara and her family successfully raised themselves from tenant farmers to leading members of society in part through a handful of strategic marriages and baptisms, through which they tied themselves to some of New Amsterdam’s most prominent families. How much she learned from Lenape people also demonstrates the importance of Native aid to the early colonists. Sara’s will indicates just how much racial oppression figured in such upward mobility in early New York, as she became a slaveholder and worked to ensure that her children and grandchildren also benefited from the system of enslavement. Yet Sara’s story also shows the limitations that gender roles could place on women. The men around her would have expected Sara to play the part of the Dutch housewife and would not have allowed her to hold a political office. Even so, Sara managed to use that assigned role in order to become an ideal translator for Dutch negotiations with Native communities. She serves as a reminder that women were a part of all the different aspects of colonization, from trade, to land acquisition, to slavery.

Footnotes:

1. Willem Frijhoff, Fulfilling God’s Mission: The Two Worlds of Dominee Everardus Bogardus, 1607-1647, translated by Myra Heerspink Scholz (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 598-600.

2. Willem Frijhoff and Marijke Spies, Dutch Culture in European Perspective: 1650, Hard-Won Unity (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 19-20.

3. Frijhoff, Fulfilling God’s Mission, 376.

4. Jaap Jacobs, New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America (Netherlands: Brill Press, 2004).

5. Frijhoff, Fulfilling God’s Mission, 384.

6. Susanah Shaw Romney, New Netherland Connections: Intimate Networks and Atlantic Ties in Seventeenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 2014), 259-269.

7. Romney, New Netherland Connections, 260.

8. Waltraud Kolb and Sonja Pöllabauer, “Women as Interpreters in Colonial New Netherland: A Microhistorical Study of Sara Kierstede,” in Introducing New Hypertexts in Interpreting (Studies): A Tribute to Franz Pöchhaker (John Benjamins: 2023), 126-146.

9. Frijhoff, Fulfilling God’s Mission, 386-387.

10. Romney, New Netherland Connections, 261-265.

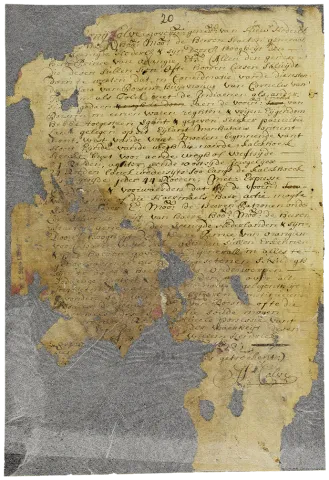

11. New York Probate Records, 1629-1971, Film #005512800, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8992-S88P?i=6. A fold in the document seems to have led some scholars to mis-transcribe the man’s name as “Ande”. For a loose translation, see “Collections of the New York Historical Society, 1892: Abstracts of Wills on File in the Surrogates Office, New York City, Vol. 1, 1665-1707,” 225-226.

12. Kolb and Pöllabauer, “Women as Interpreters,” 138.

13. Joel W. Grossman, “Archaeological Indices of Environmental Change and Colonial Ethnobotany in Seventeenth-Century Dutch New Amsterdam,” in Environmental History of the Hudson River, edited by Robert E. Henshaw and Frances F. Dunwell (SUNY Press, 2011), 77-121.

14. Grossman, “Archaeological Indices,” 111; Mrs. J. K. van Rensselaer, The Goede Vrouw of Mana-ha-ta: At Home and in Society (New York: Scribner, 1898), 355.

15. Romney, New Netherland Connections, 266.

16. Romney, New Netherland Connections, 266-267.

17. Sarah Kersted, Land Patent, June 24 1669, New Jersey State Archives, Secretary of State Deeds, Commissions, Surveys, 1650-1856 Liber 1, Part A, 1650-1672 (SSTSE023).

18. Nicole Maskiell, Bound by Bondage: Slavery and the Creation of a Northern Gentry (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, 2022), 31.

19. New York Probate Records, 1629-1971, Film #005512800, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8992-S88P?i=6.

20. Maskiell, Bound by Bondage.

21. Romney, New Netherland Connections, 149. Andrea Mosterman, Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021), 25.

22. Andrea E. Frohne, The African Burial Ground in New York City: Memory Spirituality, and Space (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press), 34, 82.

23. Grossman, “Archaeological Indices”, 113.

24. New York Probate Records, 1629-1971, Film #005512800, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8992-S88P?i=6.

Supporters

The People of New Amsterdam project is supported as part of the Dutch Culture USA program by the Consulate General of the Netherlands in New York.

The Frederick A.O. Schwarz Education Center is endowed by grants from The Thompson Family Foundation Fund, the F.A.O. Schwarz Family Foundation, the William Randolph Hearst Endowment, and other generous donors.