Reytory Angola

Enslaved Africans were first brought to Manhattan Island by West India Company in 1624 to build infrastructure for New Amsterdam. The WIC first brought men to the colony, then soon after brought women as well. Though it is difficult to pinpoint her exact moment of arrival, Reytory Angola (sometimes called “Dorothy” in the records was one of these women).

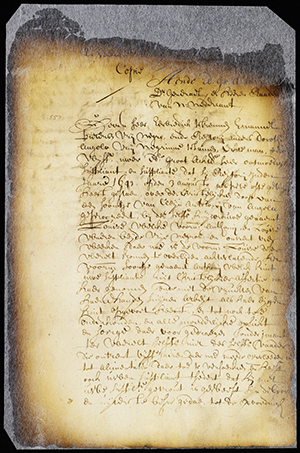

Reytory may have arrived in New Amsterdam as early as 1628, as one of the enslaved women from Angola (a major hub of the Atlantic slave trade situated on Africa’s west central coast). Our reliance on vague documents for unclear details of Reytory’s life highlights the way that archives recording and preserving human history have long been shaped by dynamics of power that historically, have been disproportionately held onto by white men in power. Nonetheless, through careful examination of the records, historians can gather details of the lives of people like Reytory—people who led full lives despite the archival silences that have hidden them from future generations.

Many of the enslaved African women who Dutch traders brought to New Amsterdam worked as domestic servants, farmed for the WIC, and worked alongside men on New Amsterdam’s roads and buildings. The women were also tasked with the responsibility of having children in order to add to a growing population of enslaved people in New Amsterdam.

Reytory first appears to us in the archival records in 1643, when she witnessed the baptism of her godson, Cleyn Anthony. But Anthony’s mother, Louise, died just four weeks after giving birth, and Reytory claimed the child as her own. Reytory eventually married another enslaved man, Paulo d’Angola, though it is unclear whether the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam formally recognized their marriage.

Angola's petition for their son's, Anthony's, freedom.

In February 1644, Paulo and ten other enslaved men petitioned then-director Willem Kieft for their freedom. Kieft agreed to free the men along with their wives but specified that all children would remain property of the WIC. Kieft’s decision was different from the laws of other European countries, which stated that a child’s status of being freed or enslaved should depend on the mother’s status. Kieft also demanded a yearly tax in farmed produce and livestock to the WIC as another condition to freedom. Reytory thus achieved only a partial freedom, for any children to which she gave birth would be automatically enslaved. And compared to her husband Paulo, the freedom that Reytory did achieve was even more uncertain because Kieft gave documentation of freedom to the men but not the women. So, Reytory’s freedom would depend upon her husband’s status as a freed man, and upon the willingness of New Amsterdam’s white inhabitants to recognize her as free.

Reytory devoted the remainder of her life to ensuring her own freedom along with her children’s, working to become financially independent by acquiring land of her own. In December 1644, through her husband Paulo, Reytory gained access to six acres of land near today’s Washington Square Park, alongside Manhattan’s other enslaved, free, and partially free Black residents. Later 18th and 19th-century sources would refer to this area, and other locations, as the “Land of the Blacks.”

Reytory’s husband died in 1652 or 1653, while she was pregnant with her son Jacob. She quickly remarried, this time to a free Black man named Emmanuel Pietersz. They could have held great affection for each other, but it is interesting to note her attachment to someone that is a Black landowner and a recognized free man by Manhattan’s white community was beneficial for her to build generational wealth and freedom.

Reytory used her financial means and her partnership with her husband to pass on her freedom to Anthony, her godson. Emmanuel successfully petitioned then-director Petrus Stuyvesant to recognize Anthony’s freedom in writing, and to acknowledge his status as heir to their land. Even though Anthony’s freedom was secured, both he and Reytory, along with other Black landowners, faced the threat of re-enslavement under future changes in the colony's laws.

Reytory’s story makes clear that despite the WIC’s efforts to retain their hold over enslaved Africans within New Amsterdam, enslaved African men and women worked hard to create their own freedom. Yet the boundaries between freedom and enslavement remained fluid, creating a kind of freedom that was always partial and often threatened. Reytory was forced to devote the entirety of her life to claiming possession over her own body and the fruits of her labor, as well as ensuring the freedom of generations of her kin, both biological and extended.