Germ City: Epidemics throughout New York’s History

Tuesday, October 23, 2018 by

This Story was originally written in Fall 2018, in conjunction with the exhibition Germ City: Microbes and the Metropolis. Read on to see how New Yorkers responded to past epidemics.

As the weather turns colder, the emails about scheduling a flu shot begin to circulate. This fall brings heightened awareness as it marks the 100th anniversary of the 1918 influenza pandemic that killed nearly 50 million people worldwide. Within New York alone, the flu claimed the lives of over 30,000 people. Most of these deaths occurred between the months of October and December. With the flu on my mind, I started to think about other deadly diseases that have drastically taken over the City. Which ones were the worst and what did the city do to prevent illnesses from spreading?

New York’s first health department was created in 1793 with the hopes of preventing a yellow fever outbreak that was spreading throughout the city of Philadelphia. Ships sailing into New York’s harbor from Philadelphia were quarantined, but this tactic only lasted for so long. By 1795, Yellow fever was making its way through New York City.

The true cause of yellow fever was unknown at the time. Many thought the disease was spread by consuming or inhaling the fumes of rotting food or coffee. Others believed the illness was imported from the West Indies. The press was reluctant to publish the extent of yellow fever due to fears of people leaving the city and the economy suffering. New Yorkers falsely believed the disease was not contagious, and by 1798, the dispersion of yellow fever had reached epidemic proportions claiming the lives of thousands. Various efforts were made to clean up certain neighborhoods most widely affected by the disease, but other than quarantining infected ships, the newly formed health department did little to prevent the sickness from spreading.

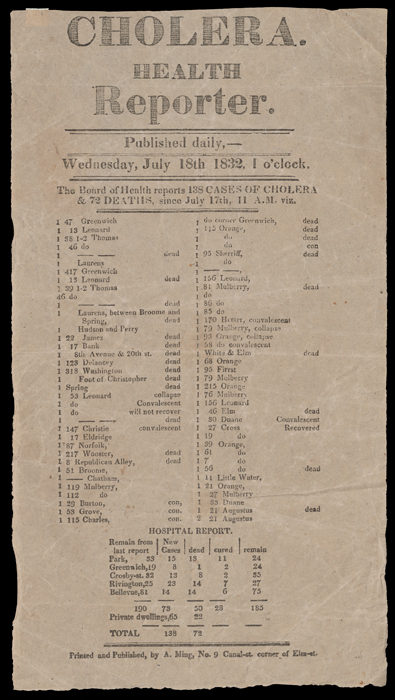

The same health department formed during the yellow fever epidemic remained relatively inactive until the first Cholera outbreak in June 1832. Once again, ships were quarantined, an effort was made to clean up the streets in affected areas, predominantly located in poorer neighborhoods of lower Manhattan, and a few poorly equipped hospitals were opened to treat the sick, but little else was done. It was believed that epidemics were just a part a life. The fact that the poorer neighborhoods were affected the worst was seen as further proof of the residents’ moral depravity. Over the next two months, over 3,500 New Yorkers would die from Cholera.

Cholera struck the city again in 1849 and remained a constant presence until 1854. Overcrowding and unsanitary living conditions in boarding houses and tenement buildings of the Lower East Side contributed to the spread of disease. Residents had little access to clean running water and an inadequate sanitation department allowed cholera to takes its toll. By 1854, Dr. John Snow of England had discovered that cholera was transmitted via water contaminated by the waste of cholera victims. Snow was able to pinpoint the transmission of cholera to a well located on Broad Street. A baby’s dirty diaper was found floating in cesspool nearby.

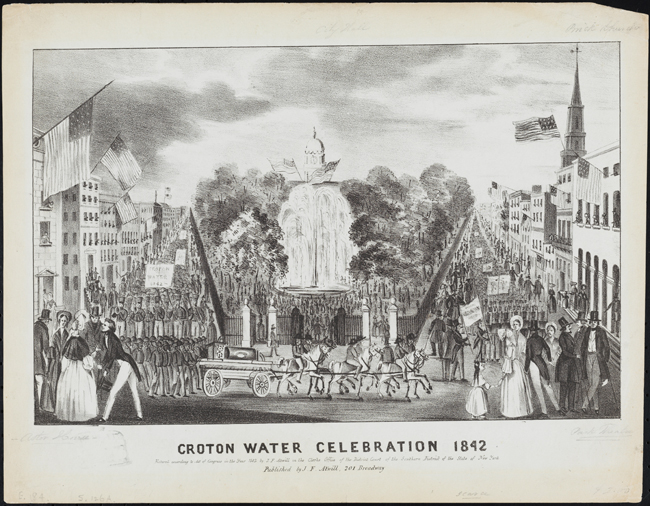

The completion of the Croton Aqueduct in 1842, the banning of pigs within the city in 1849, and a properly managed Metropolitan Board of Health all contributed to declining outbreaks of cholera within New York City but there were still other diseases to contend with.

In 1883, a young Mary Mallon emigrated to the United States. By 1906 she was employed as a cook within a wealthy household located on Long Island. Shortly after the beginning of her employment, six of the 11 members of the household fell ill with typhoid fever. The family engaged sanitary engineer George Soper to investigate the cause of illness. Soper was able to identify Mary Mallon as the first asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever. She exhibited none of the symptoms associated with the illness but was infecting those she served by not washing her hands before handling food. Soper looked further into Mary’s employment history and discovered seven of her eight previous households had suffered from typhoid. The New York City Health Department quarantined Mary on North Brother Island from 1907 to 1910. The new health commissioner Ernst Lederle released Mary in 1910 with the condition that she never work as a cook again. Mary soon broke this pledge and was discovered cooking under the alias “Mary Brown” at Manhattan’s Sloane Maternity Hospital after a typhoid outbreak in 1915. She then spent the last 23 years of her life living in forced confinement on North Brother Island.

Yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, and influenza are by no means the only epidemics to have affected New York City. Learn more about Germ City: Microbes and the Metropolis, which was on view at the Museum from September 18, 2018–April 28, 2019.