City of Workers, City of Struggle Lesson: “We Are One”

New York Women’s Activism in the Garment Industry, 1909-1990

Social Studies

Overview

In this lesson, students will analyze photographs and documents to trace the history of women’s activism in New York City’s garment industry, focusing on the 1909 strike by shirtwaist workers and the 1982 strike by women in Chinatown factories.

Student Goals

- Students will be able to describe the working conditions and organizing challenges garment workers faced in the 1900s and 1980s.

- Through analyzing flyers and photographs, students will consider the tactics and strategies workers used in order to organize and fight for reforms in their workplaces.

- Students will understand the specific challenges that women workers have faced, including the fight to win enfranchisement in the 1900s and accessing childcare in the 1980s.

- Students will reflect upon the inequalities facing today’s garment workers and research and write a letter to contemporary clothing manufacturers calling for workplace reforms.

Common Core State Standards

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.5.3

Explain the relationships or interactions between two or more individuals, events, ideas, or concepts in a historical, scientific, or technical text based on specific information in the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7

Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.9-10.7

Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question) or solve a problem; narrow or broaden the inquiry when appropriate; synthesize multiple sources on the subject, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

Key Terms/Vocabulary

Benefits, Collective, Factory, Garment, Immigrant, Piecework, Strike, Union, Uprising

Key Figures

May Chen, Connie Ip, Alice Ip, Clara Lemlich, Shui Mak Ka, Frances Perkins, Rose Schneiderman

Organizations

International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU); Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL); Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees (UNITE); UNITE HERE; Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance

Timeline

1900: The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) is formed.

1903: Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) is formed with the goal of promoting cross-class cooperation on labor issues; over the next decade the WTUL will work alongside the ILGWU to support garment workers on strike, most notably in 1909.

1909: On November 22, thousands of female garment workers gather at the Cooper Union to debate going on a general strike. The next day the “Uprising of 20,000” begins—a strike lasting for 13 weeks and ending with a contract guaranteeing wage increases for thousands of strikers.

1910: Mostly male cloak makers go on strike with ILGWU support; over 75,000 workers participate in what will be called “the Great Revolt.”

1911: On March 25, fire breaks out at the Triangle Waist Company, killing 146 garment workers. In the aftermath, a Committee on Public Safety is formed—headed by future United States Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins—to investigate the fire and lobby for new labor and safety regulations in New York City.

1938: The Fair Labor Standards Act—spearheaded by Frances Perkins—becomes federal law, ensuring minimum safety conditions in workplaces, wage standards, a maximum 40-hour work week, and overtime pay, though farmers and domestic laborers are excluded from its protections.

1965: The Immigration and Nationality Act ends the federal quota system that had discriminated against Eastern and Southern European (especially Jewish and Italian), Asian, and African immigrants to the United States since the 1920s.

1969: 23 percent of Chinatown residents are working in New York City’s garment industry.

1971: Chinatown-based Local 23-25 of the ILGWU, with a majority Chinese American membership, becomes the largest affiliate of the Union—a title it would hold until 1995.

1982: On July 15, Local 23-25 goes on strike after Chinatown manufacturers refuse to sign a new contract with the ILGWU. The one-day strike is believed to be the largest in Chinatown’s history and results in all garment-shop owners agreeing to the union’s contract.

1995: The ILGWU and the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union join to become the Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees (UNITE). It will go on to merge with the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (HERE) to form UNITE HERE.

2011: 100 years after the Triangle Waist Company fire, Bangladeshi garment worker and union activist Kalpona Akter takes the stage at the Cooper Union to speak on the need for reform and labor protections in garment factories across the globe.

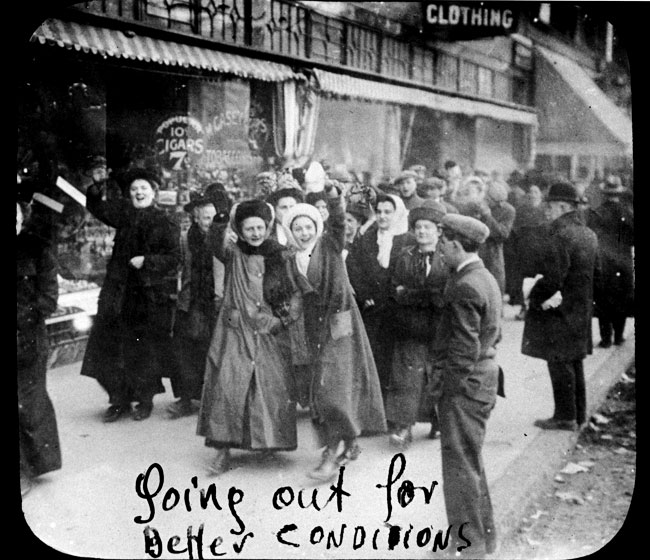

Introducing Resource 1: Photograph of shirtwaist strikers marching in winter 1909

By 1909 New York City produced 70 percent of U.S. women’s and 40 percent of men’s clothing, and larger factories were replacing tenement “sweatshops.” Workers who toiled in New York City’s garment factories faced brutal conditions and unrelenting pressure to meet ever-higher production quotas; a 1905 garment worker was expected to sew at a rate twice that of her 1900 counterpart. Most factories prohibited workers from speaking to each other on the factory floor, had few safety or fire protections, mandated a 65-hour work week, and expected workers to provide their own basic materials such as needles and thread. Many garment workers were paid through a system known as “piecework,” where workers were paid for each individual garment or portion of a garment they completed. The piecework system—in contrast to a minimum wage paid hourly—created exploitative conditions for workers as completed garments could be rejected by bosses unhappy with the quality of sewing. Employees faced huge pressure to sew as quickly as possible in order to earn enough to live upon, which in turn led to injuries and mistakes. Many factories locked their doors during business hours to prevent workers from taking breaks or stealing materials.

In 1909, 20,000 immigrant shirtwaist (blouse) workers poured into the city’s streets to demand better conditions. They challenged the idea that they could not be unionized because they were mostly young, female, and divided by ethnicity. They won higher wages and shorter hours in 320 shops, most of which also recognized the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), which represented a majority female workforce making women’s clothing. The next year, 75,000 mostly male cloakmakers launched their own strike. The 1909 and 1910 strikes also forged an enduring coalition among New York’s workers, union leaders, woman suffragists, immigrant socialists, progressives, and Democratic politicians. Together, they passed laws and created agencies to expand New York government’s reach to improve the lives of working people and their families.

While hundreds of shops agreed to recognize the ILGWU after the 1909 strike, hundreds more did not. Among those factories which refused to recognize the ILGWU was the Triangle Waist Company, located one block from Greenwich Village’s Washington Square Park. Though factory owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris did raise wages in response to the strike, they did not ameliorate any of the safety hazards workers faced at the Triangle, including locked doors, broken fire escapes, and blocked hallways and exits. On March 25, 1911, a fire at the Triangle killed 146 workers. Thousands of New Yorkers watched the fire unfold, among them activist and future United States Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. Though labor activists pushed through crucial workplace safety reforms in the fire’s aftermath, Blanck and Harris were acquitted of all criminal charges.

Document-Based Questions

- Describe what you see in this photograph. What’s happening?

- What does the title “Going out for better conditions” tell you about why these people are gathered together?

- What emotions are the strikers in this photograph displaying? Why might they be feeling this way while on strike?

- While initial media coverage of the 1909 strike downplayed its importance, an economically-diverse coalition of allies that included many of the city’s wealthiest women helped draw media attention to the strikers’ cause. Why might strikers find it important to project happiness and hopefulness to the camera in the middle of their protest?

- How might the strikers in this photograph define “better conditions” in their workplaces?

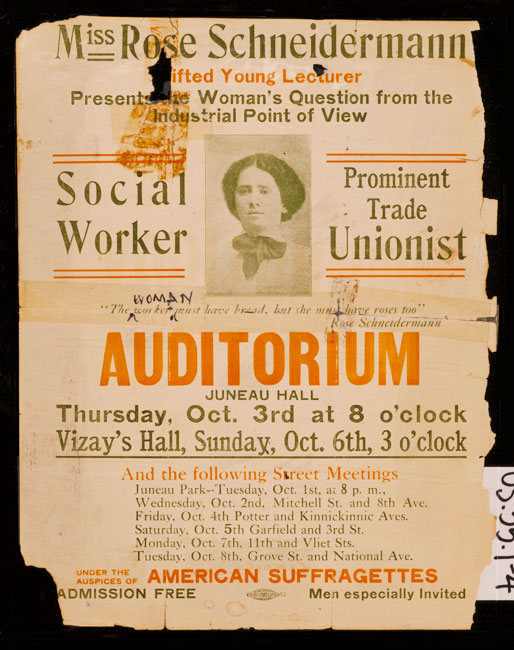

Introducing Resource 2: Flyer for lecture by Rose Schneiderman, 1912

Rose Schneiderman (1882–1972), a Polish Jewish capmaker, became an organizer as female workers forced garment unions to recognize their collective power. Schneiderman and her family immigrated to the United States in 1890. By her early teens she had joined the thousands of Jewish immigrant women working in New York City’s garment industry. After organizing the workers in her factory, Schneiderman became involved with the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) and soon left factory work to become a full-time organizer. Along with her fellow WTUL members, Schneiderman participated in the 1909 “Uprising of 20,000.” In 1926, she became president of the Women’s Trade Union League and later served as secretary of the New York State Department of Labor, where she focused on lobbying for laws shortening women’s work hours.

In addition to her work as a union organizer, Schneiderman was a fierce advocate of women’s suffrage, helping to expand the movement to include the concerns of working-class women. She argued that the women’s political enfranchisement was crucial to the larger goal of reforming workplace conditions for male and female employees alike. Schneiderman’s work within the suffrage movement often took the form of lectures like the one advertised in the flyer below as she traveled across the country from her home base in New York City to speak on behalf of the suffrage cause.

Document-Based Questions

- Describe what you notice about this flyer. What is it announcing?

- How is Rose Schneiderman being described on this flyer?

- This flyer announces that Schneiderman will speak “on the women’s question,” a phrase used to discuss the debate over women’s right to vote at the turn of the century. What connection did Schneiderman make between women’s right to vote and workers’ rights?

- On the bottom right of the flyer, the invitation reads “men especially invited.” Who published this flyer? Why might these activists feel it was important for men to attend this lecture?

- This flyer includes a quotation by Schneiderman: “The woman worker must have bread, but she must have roses too.” How should we interpret this sentence? What might bread and roses each symbolize?

- Why would the author of this flyer find it important to amend the original sentence to specify “woman worker”?

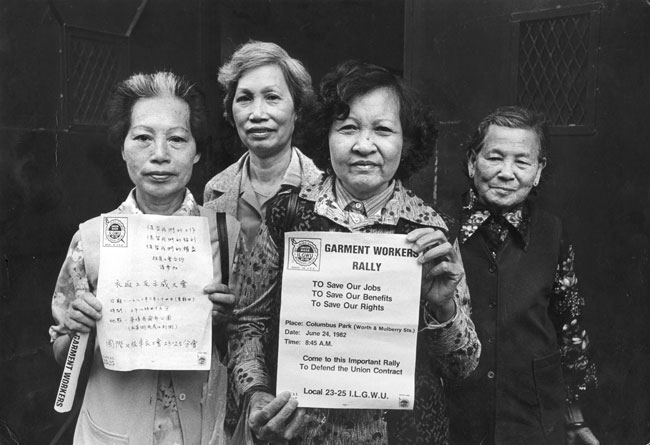

Introducing Resource 3: Photograph of striking members of the ILGWU, 1982

The 1965 Immigration and Nationalization Act dramatically changed the face of New York City’s garment industry, as newly arrived Chinese immigrants—previously barred from migrating to the United States by a quota system that limited Asian immigration—found work in garment factories. By 1975, over 10,000 women worked in factories located in Chinatown. Many labored in workshops making sportswear, often working six 12-hour days per week and facing regular abuse from bosses. Pay was low, often around $100 weekly, and most manufacturers paid workers by the piece, rather than through a minimum hourly wage.

Nearly all garment workers were members of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) Local 23-25, but few felt strong ties to the union, which did minimal Chinese-language outreach to its membership. A central complaint of union members was a lack of access to childcare. The majority of women workers had young children and the neighborhood’s available daycares were at capacity, forcing many women to either bring their children to the factories or stay home from work. Though union members had lobbied for it in the past, neither manufacturers nor the ILGWU provided affordable childcare benefits. Although workers brought their concerns over pay and benefits to the ILGWU, the union—fearful of driving employers out of the city after an exodus of manufacturers in the 1970s—took little action in response.

In 1982, Chinatown garment firms refused to sign the ILGWU contract and demanded that the union, rather than manufacturers, should provide their workers with vacation and healthcare benefits. In response, workers organized. Led by Alice and Connie Ip, May Chen, Katie Quan, and Shui Mak Ka, garment workers met with ILGWU officials, circulated calls to action throughout the community, and in some cases staged their own wildcat strikes, walking off the job without waiting for union approval. On June 24, some 20,000 immigrant women poured into Chinatown’s streets in two demonstrations targeting 60 garment manufacturers who refused to sign union contracts. Jay Mazur, then manager of Local 23-25 and later president of the ILGWU, spoke at the rally, announcing to the assembled strikers, “We are one!” Within hours, the women had persuaded nearly all firms to sign the union contract, with the rest following suit after further strike threats in later weeks. In this photograph, striking members of the ILGWU pose with a flyer for the June 24th rally.

Document-Based Questions

- Describe what you see in this photograph. What’s happening?

- How would you describe the mood of the people pictured here?

- What is the flyer they are holding calling for?

- According to the flyer, why is it crucial for garment workers to show up at this rally?

- What do you think organizers of this rally hoped to accomplish by gathering garment workers together?

- Why might it be important for these union members to display this flyer in both English and Chinese?

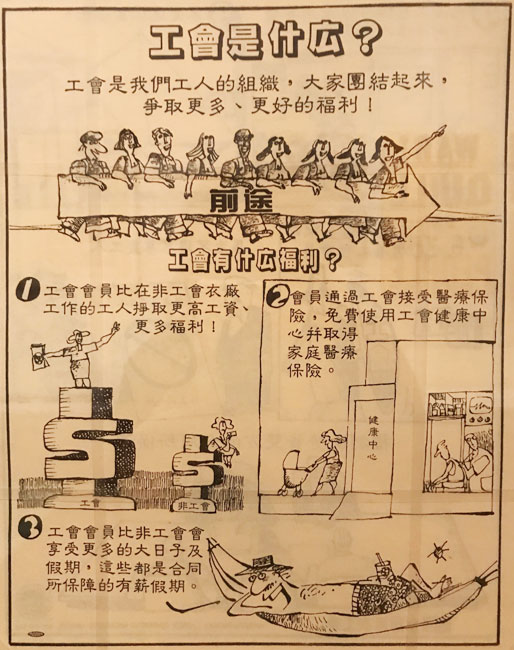

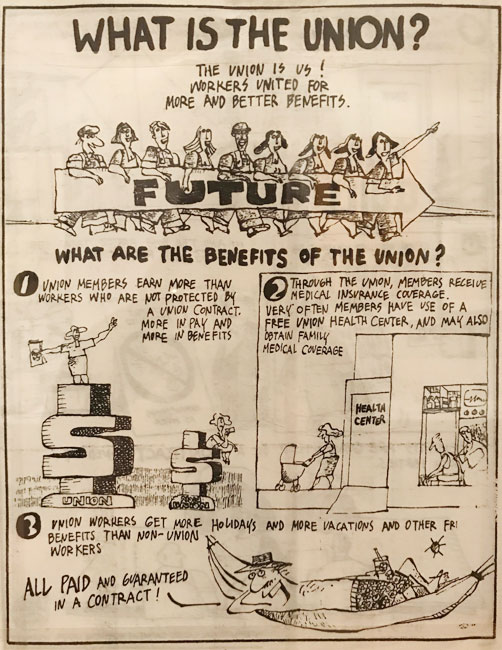

Introducing Resource 4: “What is the Union” flyer, 1990

The successful 1982 strike by Chinatown members of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) Local 23-25 did not end exploitation within the city’s garment industry, in part because non-union shops and global production kept pay rates low. Yet the shared activism of 1982 transformed the union, the Chinese American community, and the women themselves. Movement veterans went on to found the Chinese chapter of the Coalition of Labor Union Women (1984), to cofound the national Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (1992), and to leave a lasting mark on the politics and culture of New York’s growing Asian American communities.

The Chinatown strike also dramatically altered relationships between union members and union leadership. More bilingual staff were hired, and it became standard policy to translate all union communication into Chinese and Spanish. ILGWU expanded its offerings of English classes, immigration paralegal services, and health services, and set up a childcare center in Chinatown. The union also increased its presence in both daily community life and important cultural events, participating in the annual Chinese New Year parade, aiding in community protests against a proposed jail in Chinatown’s Columbus Park, and joining in local protests against Chinese state-sanctioned violence at Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

ILGWU Local 23-25 issued bilingual leaflets like this one featured below in the 1980s and 1990s that spelled out the advantages of union membership for new Chinese immigrants.

Document-Based Questions

- Describe what you notice about this flyer. How would you characterize its design and tone?

- What are the benefits of a union according to this flyer?

- What is this flyer encouraging people to do?

- This flyer was printed in both English and Chinese. Why would the creators of this flyer print it in multiple languages?

- Why would the creators of this flyer use cartoon images in their design?

Activity

Drawing upon what they’ve learned about the history of women’s activism in the garment industry in New York City, students will discuss, research, and write letters to a contemporary clothing company asking it to address exploitative and unsafe labor practices in its supply chain.

In 1909, New York City garment workers made 70% of women’s clothing bought in the United States and 40% of men’s. Today, very little of the clothing most Americans purchase is made domestically—in 2015, 97% of all clothing sold in the U.S. was imported, largely from China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India. In many of these countries, workers must contend with low wages, rampant wage theft, unsafe factory conditions, and abuse on the job. Teachers may draw upon reports published by the Worker Rights Consortium for facts and studies on global garment manufacturing (https://www.workersrights.org/).

Teachers should begin this activity by having students reflect on where their own clothing comes from (teachers may ask students to look at a few articles of clothing at home the night before this lesson and activity). Have students write down or discuss in small groups some of the following questions:

- What company makes my favorite article of clothing?

- When I look at some of my clothing tags, where is my clothing being made?

- Is any of my clothing made in the United States?

Reflecting on the issues that women in New York City’s garment industries in both the early 1900s and the 1980s identified as most important to them, students should brainstorm a list of workers’ rights and benefits they feel are most important to provide to all garment factory employees today. Their list might include:

- Living wages

- Retirement benefits

- Healthcare services

- Safe working conditions

- Childcare subsidies or centers at work

Teachers should have students research a company where activists have identified abuses or violations of workers’ rights and write a letter to that company asking them to address and remedy the issue. Teachers may find it helpful to use the Worker Rights Consortium’s news page (https://www.workersrights.org/news/) for easy access to the latest updates on workplace reporting and activism. As they craft their letters to the company, students should think about the specific reforms they would prioritize, what arguments are most compelling, and how the history and legacy of women’s labor activism in the New York City has shaped the conversation around workers’ rights.

Sources

Bao, Xiaolan. Holding Up More Than Half the Sky: Chinese Women Garment Workers in New York City, 1948-92. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Blanchard, Tamsin. “Who made my clothes? Stand up for workers’ rights with Fashion Revolution week,” The Guardian, April 22, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/commentisfree/2019/apr/22/who-made-my-clothes-stand-up-for-workers-rights-with-fashion-revolution-week.

Chan, Huiying B. “How Chinese American Women Changed U.S. Labor History,” Open City, Asian American Writers’ Workshop, May 1, 2019, https://opencitymag.aaww.org/chinatown-garment-strike-1982/.

Freeman, Joshua B., editor. City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

Quan, Katie. “Memories of the 1982 ILGWU Strike in New York Chinatown,” Amerasia Journal, 35:1 (2009): 76-91, http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/memories-of-the-1982-ilgwu-strike-in-new-york-chinatown/.

von Drehle, David. Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003.

Additional Resources

“The Kheel Center ILGWU Collection,” Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives at Cornell University, Cornell University, August 2011, http://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu/.

“Remembering the 1911 Triangle Factory Fire,” Online Exhibition, Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives at Cornell University, Cornell University, January 2011, http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/index.html.

- This online exhibition contains primary and secondary sources on the 1911 Triangle Waist Factory Fire, drawn primarily from the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) Archives, held by Cornell University’s Kheel Center.

Akter, Kalpona. “Improving the Life of Bangladeshi Garment Workers.” Speech. Oxfordshire, England, UK, November 29, 2018. VOICES Conference, Business of Fashion, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xQjd-owsBms.

Greenberg, Zoe. “Overlooked No More: Clara Lemlich Shavelson, Crusading Leader of Labor Rights,” New York Times, August 1, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/01/obituaries/overlooked-clara-lemlich-shavelson.html.

Pellett, Gail and International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, Local 23-25. We Are One. Documentary, 1982, http://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu/archives/filmVideo/index.html.

Field Trips

This content is inspired by the exhibition City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York. Consider bringing your students on a field trip to visit this exhibition before January 5, 2020! Find out more.

Acknowledgments

City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York, its associated programs, and its companion publication are made possible through the generous support of The Puffin Foundation, Ltd.

The Frederick A.O. Schwarz Education Center is endowed by grants from The Thompson Family Foundation Fund, the F.A.O. Schwarz Family Foundation, the William Randolph Hearst Endowment, and other generous donors.