The Eclectic Trade Card Collection of Harry Twyford Peters

Tuesday, March 22, 2022 by

Harry Twyford Peters was born in Greenwich, Connecticut in 1881, the son of Samuel T. Peters and Adeline Peters (née Mapes Elder). Peters entered the coal business after graduating from Columbia College in 1903. He worked at Williams and Peters, his father’s firm, later becoming a partner and its president. Peters inherited $500,000 dollars upon the death of his father in 1921–the equivalent of over $6 million dollars by today’s standard–making him a very wealthy man.

Peters was an avid collector of American prints and a leading authority on the firm Currier & Ives, a prolific American printmaking firm that operated out of New York City. With generous support from the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation, the Museum has begun to digitize Peters’ extensive collection of trade cards, and manuscripts.

Trade Cards

In May of 1876, the Prussian-born American lithographer Louis Prang (1824-1909) set up his booth at the American Centennial fair in Philadelphia and began to print trade cards for fairgoers. Trade cards--a predominantly visual precursor to modern-day business cards, first introduced to the U.S. in the 18th century and updated with color in printing in the 1840s--were initially used as a form of advertising by local businesses. Eventually eclipsed by magazine advertising, trade cards enjoyed a brief period of commercial prominence in North America from the early 1860s to the late 1880s. Initially, small businesses would commission the cards in small orders from local lithographers and craftsmen. Businessmen would commission specific images relevant to their trades from local engravers, print the name and address of their business on the back, and then distribute them among their customer base. Ideally, trade cards would make a visual impression, leaving the name of the tradesperson’s business in mind for future purchases. Usually, this visual impression would be left by lithography.

Having been part of everyday commerce for well over a century, Prang--a fascinating figure in his own right, a Georgist who fled Prussia after his involvement in German revolutionary activities in 1848--brought an interesting innovation to the field of trade card lithography. Prang’s 1876 booth promised the innovation of stock trade cards--cards whose images were broadly applicable to a wide range of uses. Historian Jennifer M. Black argues in her 2009 paper “Corporate Calling Cards: Advertising Trade Cards and Logos in the United States 1876-1890” that the American Centennial was where trade cards became a true token of American economy, visually linking large corporate brand-recognition between states and hamlets. In addition, Black argues that Prang’s innovation of stock cards, and the fact that they were distributed so widely at the American Centennial was instrumental in elevating stock cards’ role in U.S. economic culture. Black writes that “trade cards fused consumption with entertainment, gift culture, and sentimentalism.” Through a certain economic-cultural lens, trade cards were a perfect summary of American culture: At once whimsical, frivolous, pseudo-relational and deeply economically motivated. In short, according to Black, trade cards’ function followed two primary avenues: One economic, the other expressive.

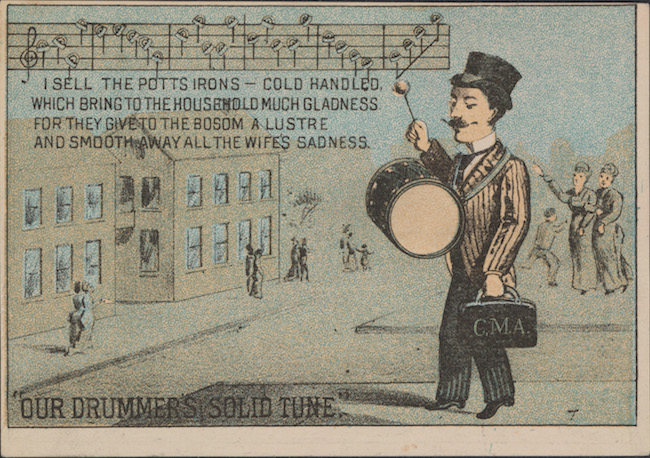

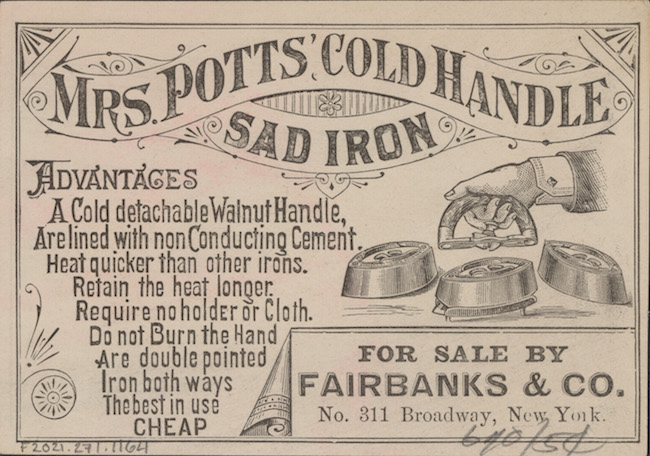

Elsewhere at the fair, Mary Florence Potts (1850-1922) was extolling the virtues of her recently patented invention, the “Cold Handle Sad Iron.” Potts, a self-described “inventress,” came of age in a time when irons were heavy metal behemoths that weighed anywhere between five and ten pounds and required dense mittens during use in order to avoid burns. Potts’ invention improved the traditional iron in two primary ways. First, her patent was the first to include multiple bases to the iron, so that the person ironing would not have to pause the work while waiting for the iron to heat back up again--they could simply keep an extra base warming during the first segment of ironing, then swap out bases when the first cooled down. Second, as the name of her patent suggests, Potts’ iron posed no real threat to the ironer, temperature-wise. Whereas burns and mittens were a part-and-parcel aspect of ironing in eras past, Potts’ iron made it so that people, usually women, could iron in relative comfort.

Born in 1880, Harry T. Peters would have barely missed the trade card heyday, and the revelation that was Potts’ cold-hand iron. But he held a collection of documents that reflect both Prang’s innovation in the trade card-sphere, and Potts’ invention of the cold-handle sad iron: That is, a lithographic trade card extolling the virtues of Mary Potts’ new invention.

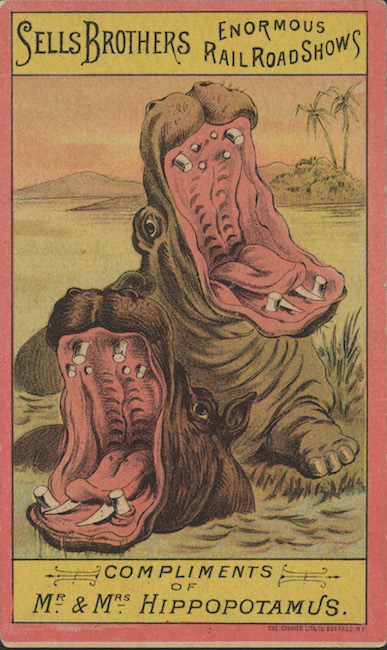

As a leading expert on the American lithography firm Currier & Ives, Peters had a passion for the antiquated art form, which manifested in three separate books: Currier & Ives: Printmakers to the American People (1929), America on Stone: the Other Printmakers to the American People (1931), and California on Stone (1935). Understandable, then, that Peters possessed a large trade card collection, which the Museum of the City of New York currently maintains as part of its permanent collection. The cards range in subject matter from housewares to food and hospitality to entertainment. A trade card advert for Harrison and Gourlay’s comedic play “Skipped by the Light of the Moon" and Sells Brothers’ Enormous Railroad Shows, featuring a married, yawning hippopotami, depict the vibrant visual potential of trade cards, as well as their potential for inserting humor into everyday life.

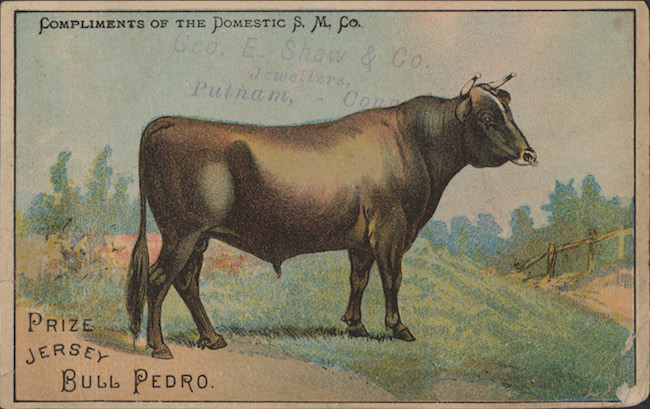

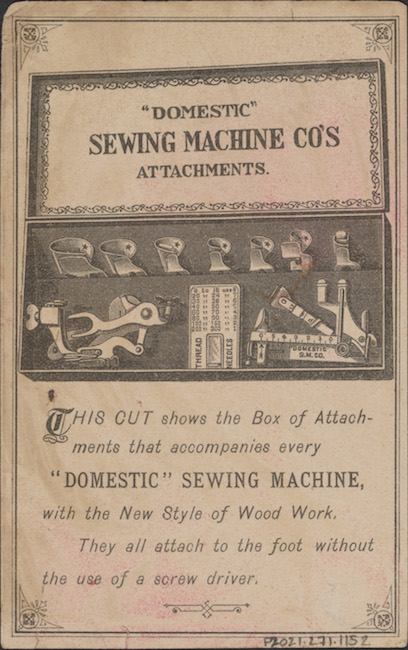

Trade cards’ relationship to lithography, as well as their status as antique objects by the time Peters reached an age to collect them, might explain the abundance of unusual trade cards in his collection. Lithography was integral to the viability and relative democratization of trade cards, which may explain Peters’ collection, at least in part. While there are plenty of intuitive, straightforward trade cards in his collection, there are a significant number of trade cards where the image is discordant to the business or product. For instance, Domestic Sewing Machine Co. had a whole series of trade cards depicting frank, context-less portraits of lilvestock. Why?

The fact that a significant number of card images do not reflect the product they are advertising is perhaps a direct legacy of Prang’s innovation of stock trade cards. That said, the cards in Peters’ collections are by no means neutral. I suspect that Peters selected the quirkiest, most unusual cards he could. The novelty of Peters’ cards--their humor and absurdity--might have been a specific quality Peters sought out as a collector.

The cards have both the arch irony of contemporary New Yorker cartoons and the gleeful absurdity of medieval marginalia. In fact, several of Peters’ trade cards have marginalia of their own. The cards are both sweet, and unnerving. They are irreverent and nostalgic. They reference fairy tales, finding that elusive sweet spot between quirk and kitsch.

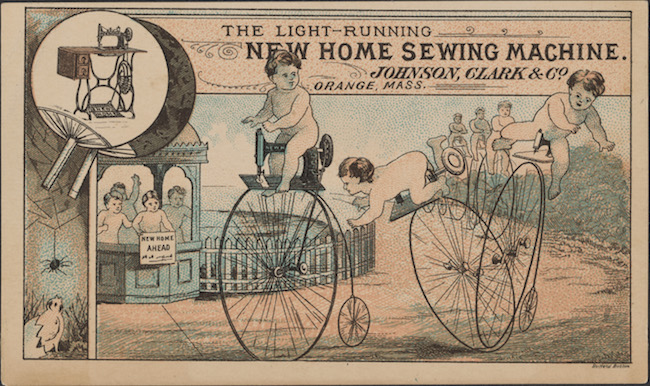

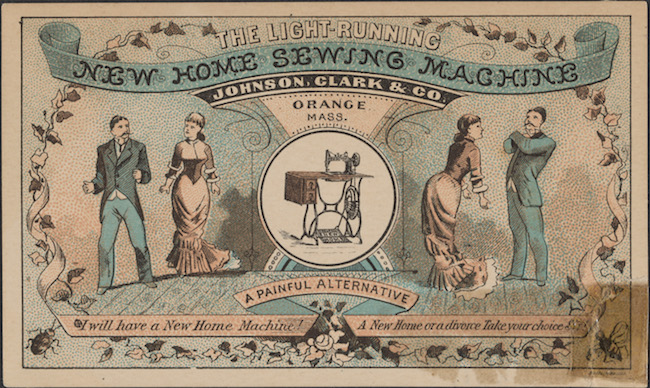

Consider Johnson, Clark & Co’s advertisement for the Light-Running New Home Sewing Machine. It depicts a parade of infants, riding 20th century bicycles whose seats are--you guessed it--the aforementioned sewing machines. In a nearby gazebo, a throng of fellow babies cheer the tiny bicyclists on, with an encouraging sign that reads “New Home Ahead.” It is, in every way, completely absurd. Besides the sewing machine-cum-bicycle motif, it’s not entirely clear what the image has to do with New Home Sewing Machines. Yet, the image is funny and gripping, with enough details to leave the viewer looking at it for a long time. In that sense, it probably fulfilled its market purpose, and brought smiles to many consumer’s’ faces. It may have even sold a sewing machine or two.

Other cards predict marital woes that will occur if the consumer does not purchase the advertised product. In a New Home Sewing Machine card, for instance, a couple bickers over the wife’s desire to invest in the product. “A New Home or a divorce, Take your Choice sir!” she pleads, with the picture’s zippy caption reading, “a painful alternative.”

Peters’ trade card collection is just a sampling of his long career writing about the history of lithography in the United States. A leading expert on the evolution and cultural role of printmaking in the U.S., Peters devoted his life to the preservation and interpretation of prints and lithographs, notably those by the firm Currier & Ives. In a way, this is an extension of Peters’ own mission in his life and career. Harry Peters saw lithography, and printmaking more generally, as an important part of cultural heritage. The Museum of the City of New York’s emphasis on cultural history, and especially the evolution of New York’s built environment, dovetail with Peters’ goal beautifully.

Click here to access Harry T. Peters papers (1790-1988) finding aid.

This post was written by India Kotis, Collections Fellow, Special Projects, and edited by Lauren Robinson, Associate Director of Collections Access.