Garment Workers

Upheaval in the Garment Trades

1900-1915

Ongoing

Back to Economic Rights

In the early 20th century, New York was the largest city and garment production the largest manufacturing business in America. The garment trade was made possible by tens of thousands of immigrant workers, who labored long hours under unsafe conditions in crowded tenements or factories.

On November 22, 1909, immigrant worker Clara Lemlich of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) called for a General Strike. Lemlich’s “Uprising of the Twenty Thousand” and a devastating fire at the Triangle Waist Company factory in Greenwich Village in 1911 illuminated the contributions of working women and made labor unions key players in the life of the city.

New York working people had been organizing unions since 1794, when the city’s industrial revolution began creating wage workers distinct from business owners. But the garment activists of 1909-1911 transformed the city’s labor movement and ushered in a new era, one in which labor unions—and working women in particular—became central players in the city’s economy.

Alongside labor activists, elected officials and Tammany Hall reformers made New York a model of workplace legislation, and unions became crucial to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Yet in the mid-20th century, many garment factories left in search of lower costs and fewer regulations, and union power diminished. Unions criticized manufacturers for abandoning New York, while manufacturers blamed unions for keeping labor costs too high. But in recent years, organized labor has made new inroads in the service economy, and the garment industry has renewed its emphasis on “Made in New York.”

Meet the Activists

Clara Lemlich

Clara Lemlich

Clara Lemlich of Local 25 International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union set the “Uprising of Twenty Thousand” in motion in 1909 when she declared “I am a working girl” and called for a general strike. Lemlich and her fellow strikers endured months of picketing and physical intimidation and violence before winning important concessions. A Jewish-Ukrainian immigrant, Lemlich joined the labor movement weeks after arriving in the United States and remained a lifelong labor activist.

Image Info: ca. 1910, Courtesy UNITE HERE Association, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins

Consumer advocate Frances Perkins witnessed the Triangle Waist Company fire from a nearby street. In the fire’s wake, she joined the Factory Investigating Commission (1911-1915), with Al Smith and Robert Wagner Sr., to press for change. They uncovered widespread, unsafe work conditions, which led to legislation that made New York the nation’s leader in workplace safety regulation. Perkins would later become Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor, the first woman to serve in a cabinet post.

Image Info: ca. 1912, Courtesy Frances Perkins Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Alva Belmont

Alva Belmont

Wealthy society figures and woman suffragists like Alva Belmont collaborated with the Women’s Trade Union League, founded in 1903 to forge a movement for female workers’ rights across class boundaries. Wealthy members of the so-called “Mink Brigade” used their automobiles to bring strikers to rallies, while Belmont paid the bail of arrested strikers.

Image Info: George Grantham Bain, ca. 1915, Museum of the City of New York, Portrait Archives, F2012.58.87.

Rose Schneiderman

Rose Schneiderman

Working-class activists came to the fore in mobilizing the mostly female strikers of Local 25 during the 1909-1910 International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) strike. Along with Clara Lemlich, immigrant worker Rose Schneiderman became a public figure during the “Uprising of Twenty Thousand,” and she went on to a long career as a feminist and labor activist in the Women’s Trade Union League.

Image Info: 1915, Courtesy Rose Schneiderman Collection, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University.

Objects & Images

Workers At A Small Bench Hand Finish Garments While Managers Look On

Workers At A Small Bench Hand Finish Garments While Managers Look On

Garment workers often labored long hours in unsafe conditions. While workplace abuses did not end after the Triangle fire, the legislature in Albany passed over 20 new laws, and the city enacted 30 ordinances regulating safety, hours, and conditions in thousands of factories. Female garment workers put themselves at the center of the city’s union movement, which grew from 30,000 to 250,000 members between 1909 and 1913.

Image Info: 1910, Courtesy UNITE HERE Association, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Industrial Table Model Sewing Machine

Industrial Table Model Sewing Machine

This sewing machine is a slightly later model than those used by garment workers in overcrowded factories and tenement buildings in the early 20th century. Garment work also included frequent hand-stitching.

Image Info: ca. 1920, Union Special Trade Mark, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Myron Zuckerman, 98.175.3.

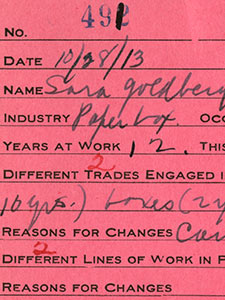

Cards From The New York State Factory Investigating Commission Records

Cards From The New York State Factory Investigating Commission Records

The Factory Investigating Commission documented the ongoing reality of low wages, long hours, and hazardous conditions in the state’s factories. On the back of one of these cards, an investigator jotted down the words of immigrant Sara Goldberg, who earned six dollars for a 53 ½ hour work week in a Henry Street paper box company: “I thought I was coming to a golden land—& struck a factory. A grave.”

Image Info: 1911, Courtesy New York State Archives.

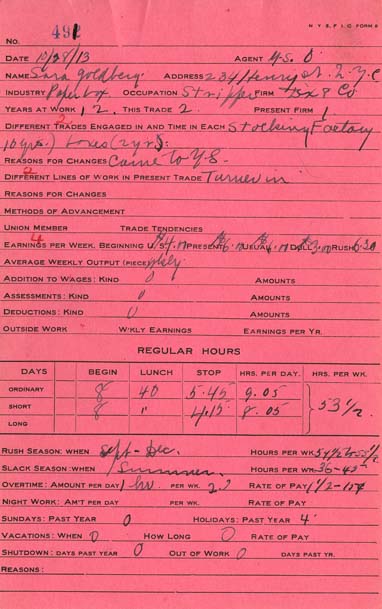

Strike Pickets

Strike Pickets

Shirtwaist workers with the International Ladies’ and Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), mostly young immigrant Jewish and Italian women, went on strike from November 1909 through February 1910. The “Uprising of Twenty Thousand” won wage and hours concessions, while owners kept the right to hire non-union workers.

Image Info: Photographer unknown, February 5, 1910, Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-04505.

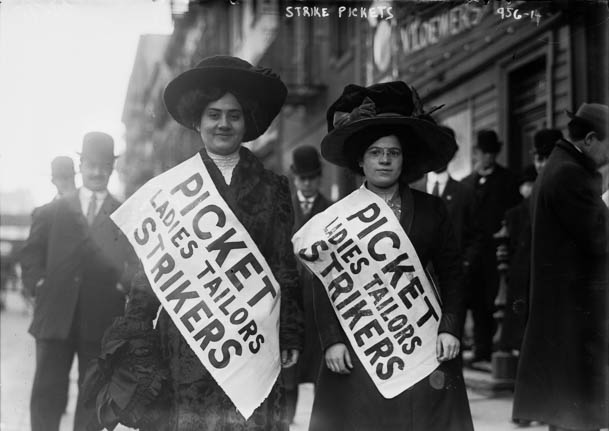

Triangle Fire, March 25, 1911

Triangle Fire, March 25, 1911

When an accidental fire raced through the top three stories of the Triangle Waist Company factory in Greenwich Village, hundreds of blouse makers escaped on elevators and stairs. Others were blocked by a locked exit door or trapped on the fire escape. Firemen’s ladders could not reach them, and dozens of people jumped to their deaths. Twenty-one-year-old pipefitter Victor Joseph Gatto witnessed the fire from Washington Square Park. Over 30 years later, he painted this vivid depiction of the fire from memory.

Image Info: Victor Joseph Gatto, 1944-1945, oil on canvas, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Mrs. Henry L. Moses, 54.75.

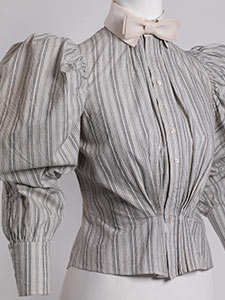

Shirtwaist

Shirtwaist

The shirtwaist, a mass-produced blouse marketed in a variety of styles and prices, became enormously popular in the late 19th century. Made in New York factories, the shirtwaist symbolized the “New Woman,” freed from restrictive traditional garments and ready to participate in a widening array of public activities, including wage labor and union activism.

Image Info: Gray and white striped cotton with linen collar, ca. 1895, Fisk Clark & Flagg, E.A. Morrison & Son, 898 Broadway, New York, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Mrs. John Hubbard, 41.190.22.

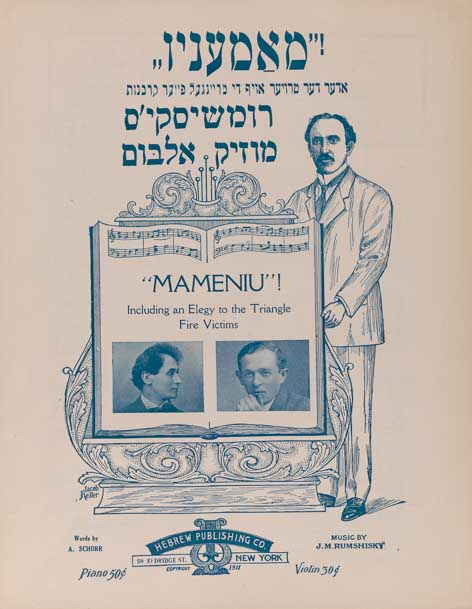

Sheet Music, “Mameniu, With An Elegy To The Triangle Fire Victims”

Sheet Music, “Mameniu, With An Elegy To The Triangle Fire Victims”

Sold in sheet music form for singing and playing at home, the Yiddish song "Mameniu (Mama Dear)" included lyrics about a mother who had lost her daughter in the Triangle Waist Company fire.

Image Info: A. Schorr and J.M. Rumshisky, Hebrew Publishing Co., New York, 1911, Courtesy Steven H. Jaffe.

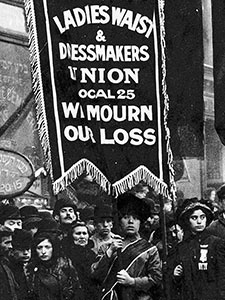

Members Of Local 25 And United Hebrew Trades With Banners March In The Streets After The Triangle Fire

Members Of Local 25 And United Hebrew Trades With Banners March In The Streets After The Triangle Fire

The Triangle Waist Company fire galvanized the city’s workers, especially its Jewish and Italian garment makers. The Union Hebrew Trades and other union locals marched in mourning, while Yiddish- and Italian-language publishers issued newspapers and song sheets deploring the fire.

Image Info: 1911, Courtesy UNITE HERE Association, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Photographs Of Labor Strikes And May Day Rallies

Photographs Of Labor Strikes And May Day Rallies

These photographs show women workers in New York’s garment trade and other industries participating in labor strikes across the city, as well as celebrating International Workers’ Day on May 1st, also known as May Day.

Image Info: ca. 1909-1920, Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-41871, LC-B2-3749-8, LC-USZ62-33530, LC-B2-3832-7.

Former New York Governor Al Smith And Senator Robert F. Wagner

Former New York Governor Al Smith And Senator Robert F. Wagner

Democratic State Assembly leader Al Smith and State Senator Robert Wagner Sr. represented a new Tammany Hall strategy: win votes by supporting labor legislation, woman suffrage, and other reforms. Smith later became New York governor (1919-20, 1923-28) and the first Catholic presidential candidate (1928). In the United States Senate, Wagner sponsored the National Labor Relations Act (1935), which guaranteed the right of workers to unionize and became the hallmark of New Deal labor law.

Image Info: Photo by John Tresilian/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images, 1934.