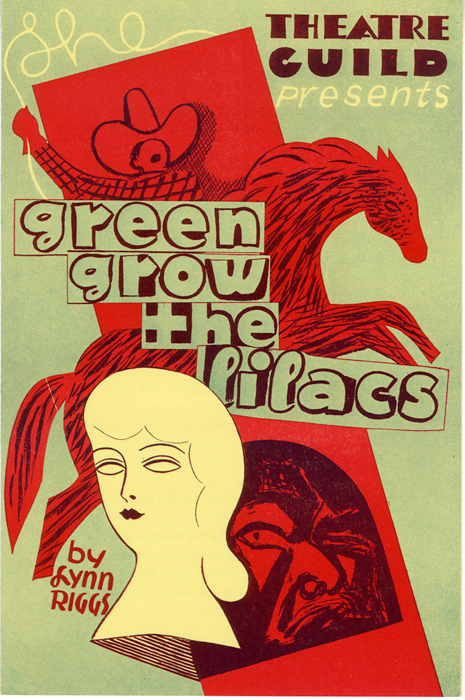

Green Grow the Lilacs: A Play with Songs

Tuesday, March 13, 2018 by

The curtain rises on a young cowboy in love. The audience first sees him on his way to visit the object of his affection, the lovely Laurey who lives with her elderly aunt. The time is about 1900, the place is a territory out west soon to become a state. The cowboy courts Laurey, but she, confused by her feelings, rejects his invitation to a local party. Instead she accepts the company of Jeeter Fry, the somewhat unsavory man who runs her aunt’s farm. Curly, our lonesome cowboy, finds solace singing the old folk song “Green Grow the Lilacs.” There’s a party, a fire, a wedding, a death, and more folk songs still to come in the action of the play, but author Lynn Riggs titles his work after this song.

Green Grow the Lilacs opened at the Guild Theatre on January 26, 1931. The play was met with mixed response and ran for an underwhelming 64 performances before closing. In his review, New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson remarked that the play “has no interest in the dramatic significance of its material…But it has a warming relish of its characters. How alive they are!”

It was that same life that captured the interest of producer Theresa Helburn when she saw a regional production of the play in 1941. Helburn was one of the co-founders of the Theatre Guild, the company that produced the original Broadway run of Green Grow the Lilacs. Inspired by the use of folk songs and dancing, she approached composer Richard Rodgers and his writing partner Lorenz Hart about turning the play into a musical. Rodgers was interested, but Hart, ultimately, was not. Rodgers connected with Oscar Hammerstein II, a lyricist who also happened to be looking into adapting Riggs’s play.

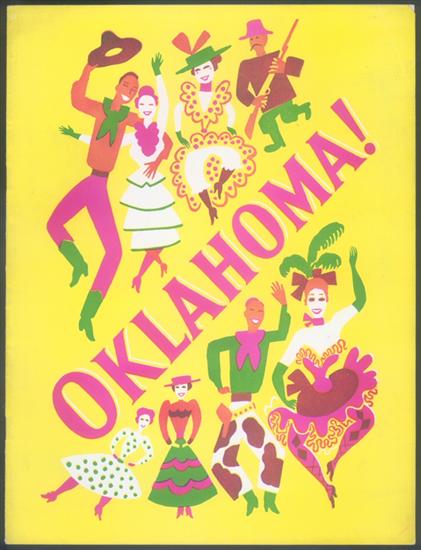

With their first collaboration, titled Away We Go!, both men were able to work in their preferred method. Hammerstein first wrote the lyrics to which Rodgers then composed the melody. Though retaining much of the play’s plot, Hammerstein made several changes to the book. Some were cosmetic (Jeeter Fry became Jud Fry), some were more substantial. For example, the supporting character of Ado Annie was expanded and given her own love triangle, a comic one that mirrored the main dramatic action between Curly, Laurey, and Jud. Finally, just before the show opened on Broadway, a new song was added. This rousing group number was called “Oklahoma,” and it became the new title of the show.

The landmark musical Oklahoma! turns 75 this month, and its significance cannot be overstated. When it opened on March 31, 1943, it forever changed what was possible for musical theater, and it introduced the songwriting team of Rodgers and Hammerstein, a creative partnership that would become one of the most successful and influential in America. Be sure to check back with Stories in a few weeks when we look at the impact and legacy of Oklahoma!

![A museum photo by Alvin Colt of [Macy's Shoppers in Here's Love] in 1963.](https://www.mcny.org/sites/default/files/styles/mcny_col_3_thumbnail/public/69_96_43-thumb.jpg?itok=x5c9oAnr)