From Dazzling to Dirty and Back Again: A Brief History of Times Square

Tuesday, July 14, 2015 by

Originally known as Long Acre (also Longacre) Square after London’s carriage district, Times Square served as the early site for William H. Vanderbilt’s American Horse Exchange. In the late 1880s, Long Acre Square consisted of a large open space surrounded by drab apartments. Soon, however, the neighborhood began to change. Electricity, in the form of theater advertisements and street lights, transformed public space into a safer, more inviting environment. Likewise, the construction of New York’s first rapid transit system, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), gave New Yorkers unprecedented mobility in the city.

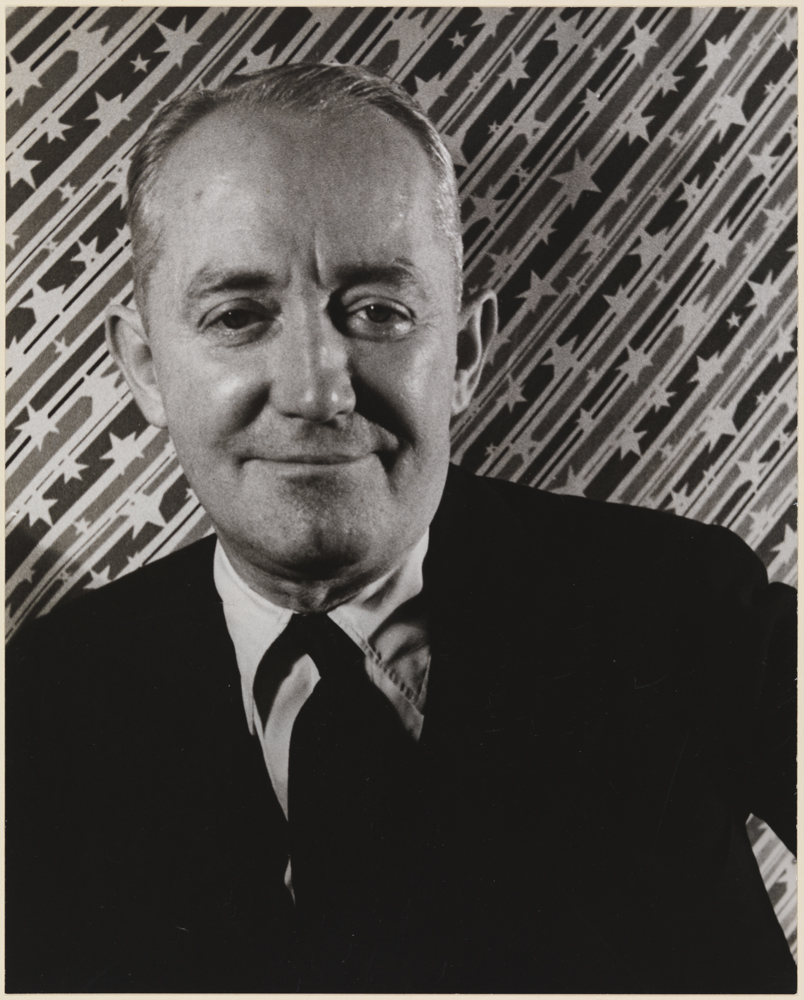

The announcement of the IRT spurred real estate speculation by shrewd businessmen who believed that increased foot traffic in the area would generate profits. Adolph S. Ochs, owner and publisher of The New York Times from 1896 to 1935, saw an opportunity and selected a highly visible location to build the Times Tower, which was the second tallest building in the city at the time. In January 1905, the Times finally moved into their new headquarters, built between Broadway and Seventh Avenue and 42nd and 43rd Streets. The previous spring, Mayor George B. McClellan signed a resolution that renamed the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue from Long Acre Square to Times Square. Ochs told the Syracuse Herald, “I am pleased to say that Times Square was named without any effort or suggestion on the part of The Times.” Yet, he clearly felt proud: the new building represented “the first successful effort in New York to give architectural beauty to a skyscraper,” he said. Within a decade, the Times outgrew their space and moved to a new location, but not before starting a tradition that continues today: the New Year’s Eve spectacular. Ochs staged the first event to commemorate the new building and crowds still gather today to bring in the new year.

![World Wide Photos, Inc. [Adolph Ochs.], ca. 1915-1935. Museum of the City of New York. F2012.58.976](/sites/default/files/f2012-58-976_0.jpg)

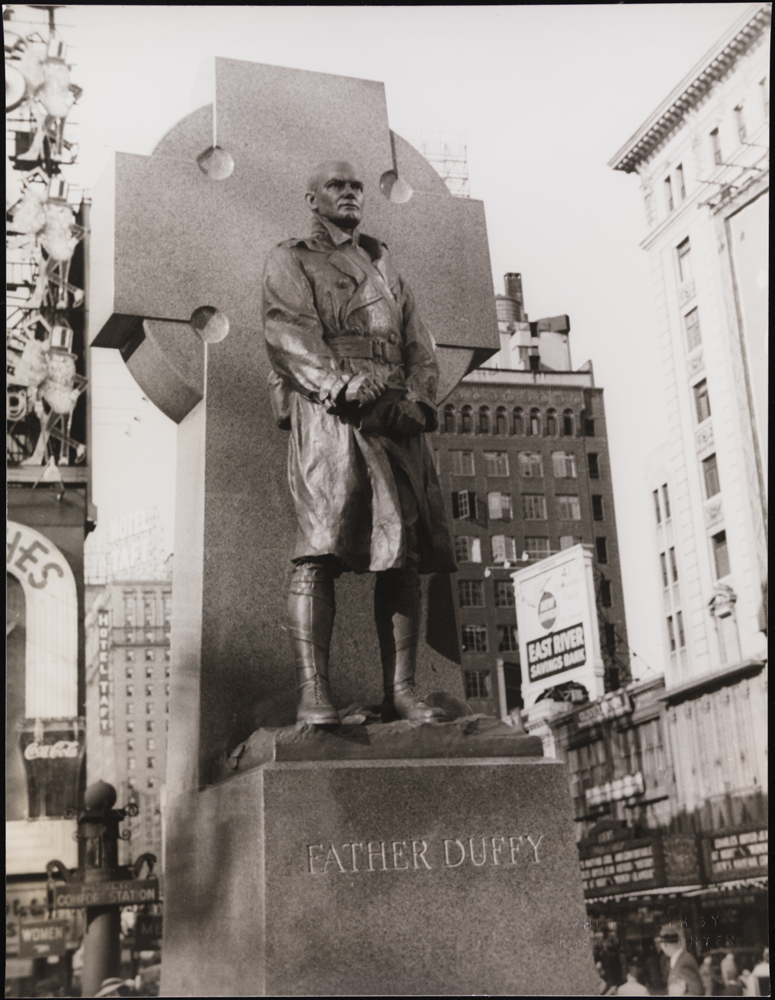

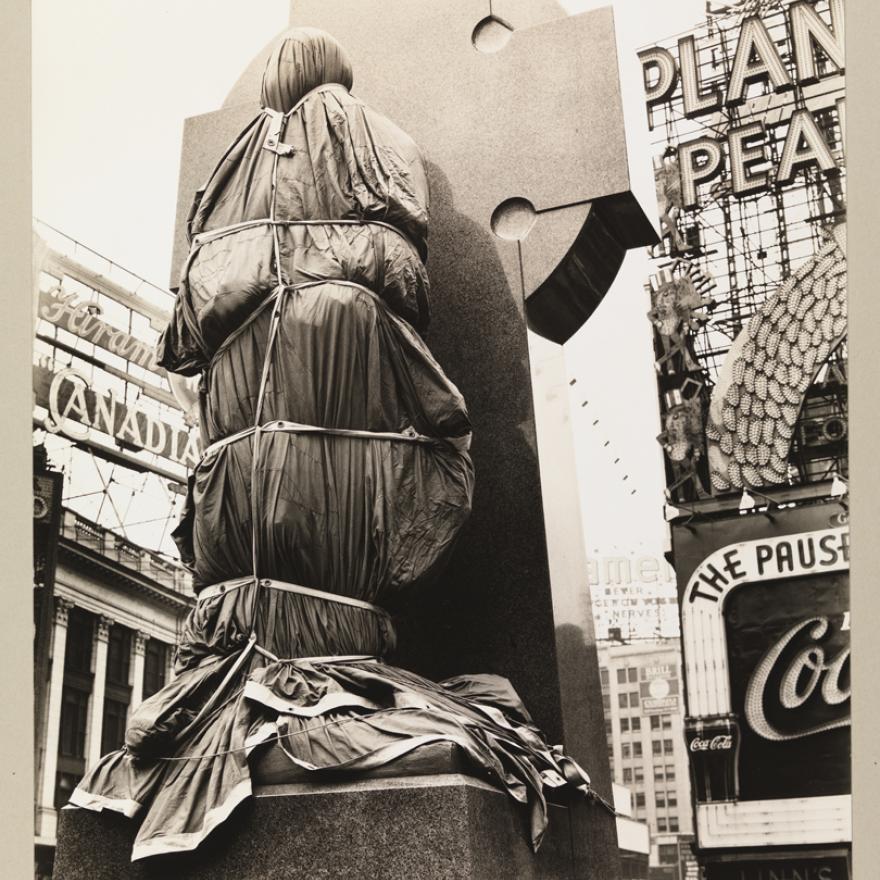

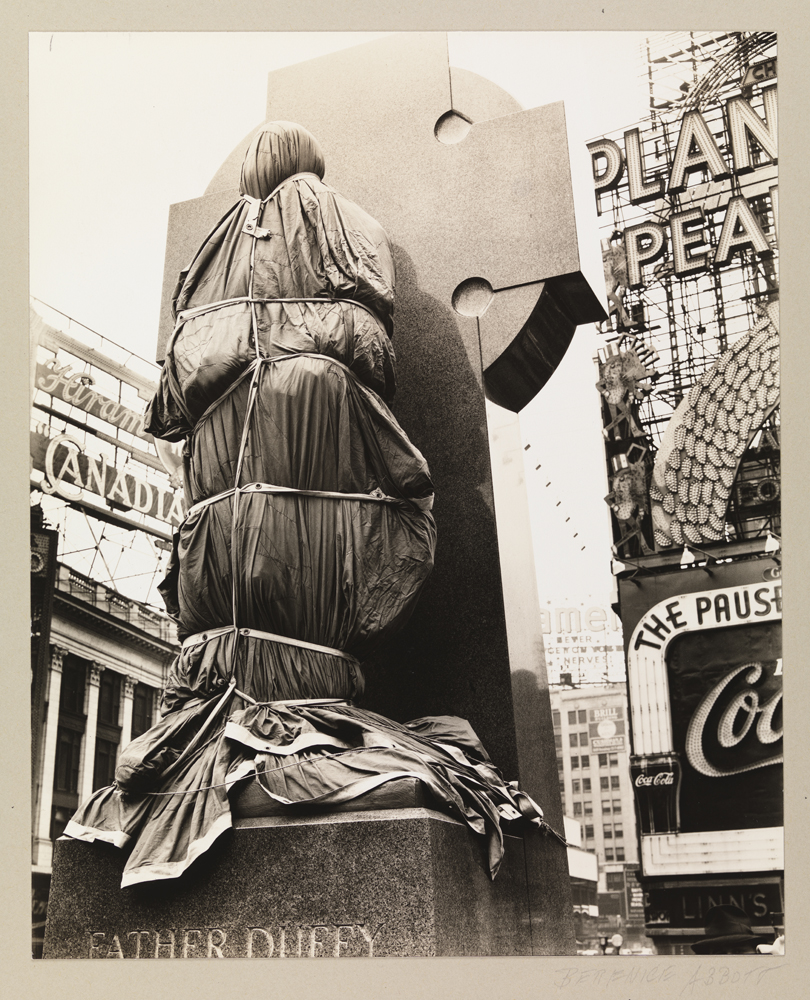

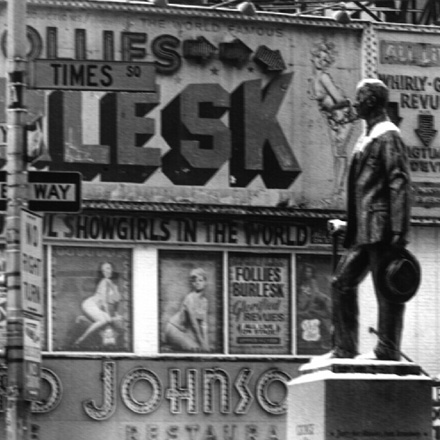

Although the Times moved to a new location, the tower still stands as a focal point in Times Square. Similarly, two statues have remained prominent monuments in the area. Father Duffy Square encompasses the northern triangle of Times Square. In 1909, a temporary eight-ton statue entitled Purity (Defeat of Slander) by Leo Lentelli dominated the space. Now, statues of Father Duffy and George M. Cohan grace the scene. Born in Canada, Father Francis Patrick Duffy (1871-1932) eventually moved to New York City. He served as a military chaplain in both the Spanish-American War and World War I. Upon his return to the city, he became pastor of Holy Cross Church, located at 237 West 42nd Street. His statue, designed by Charles Keck (1875 – 1951) faces his former church. The bronze statue of George M. Cohan (1878 – 1942), a composer, playwright, and actor, sits at the park’s southern end. He is best known for his hit song, Give my regards to Broadway: “Give my regards to Broadway / Remember me in Herald Square / Tell all the gang at 42nd Street that I will soon be there.”

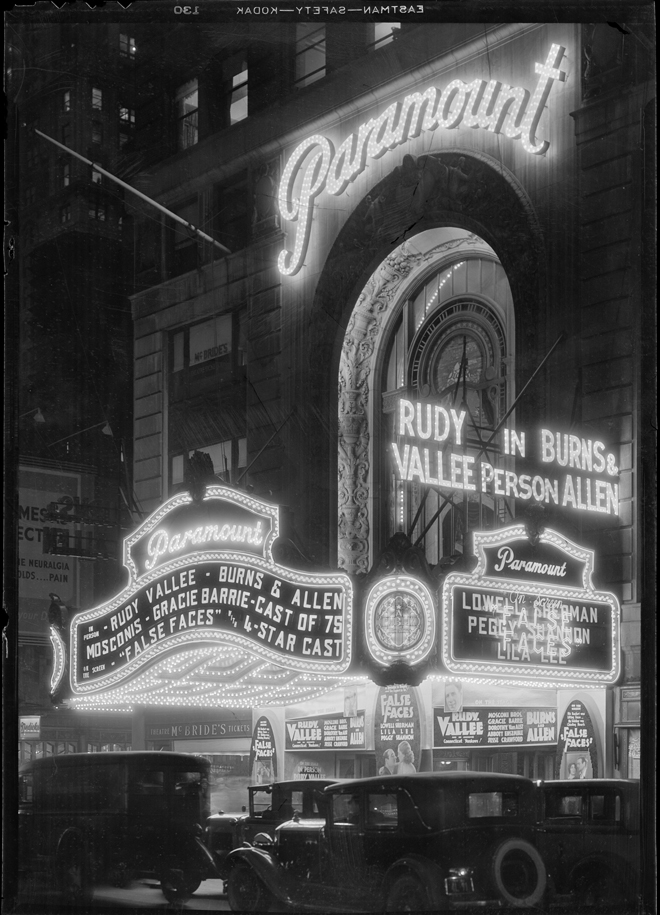

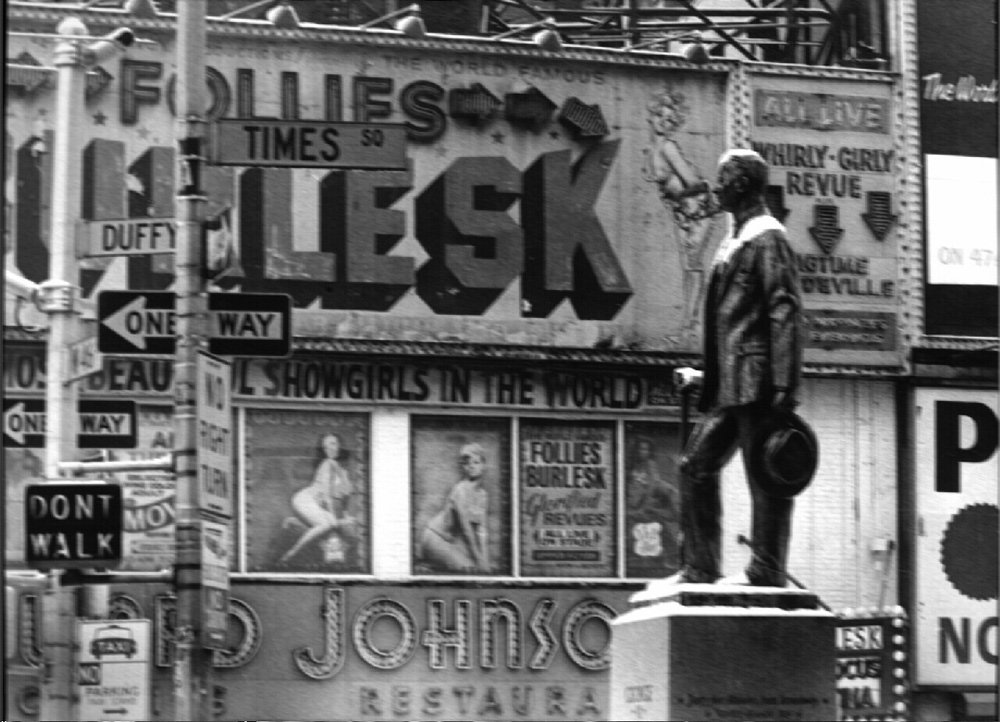

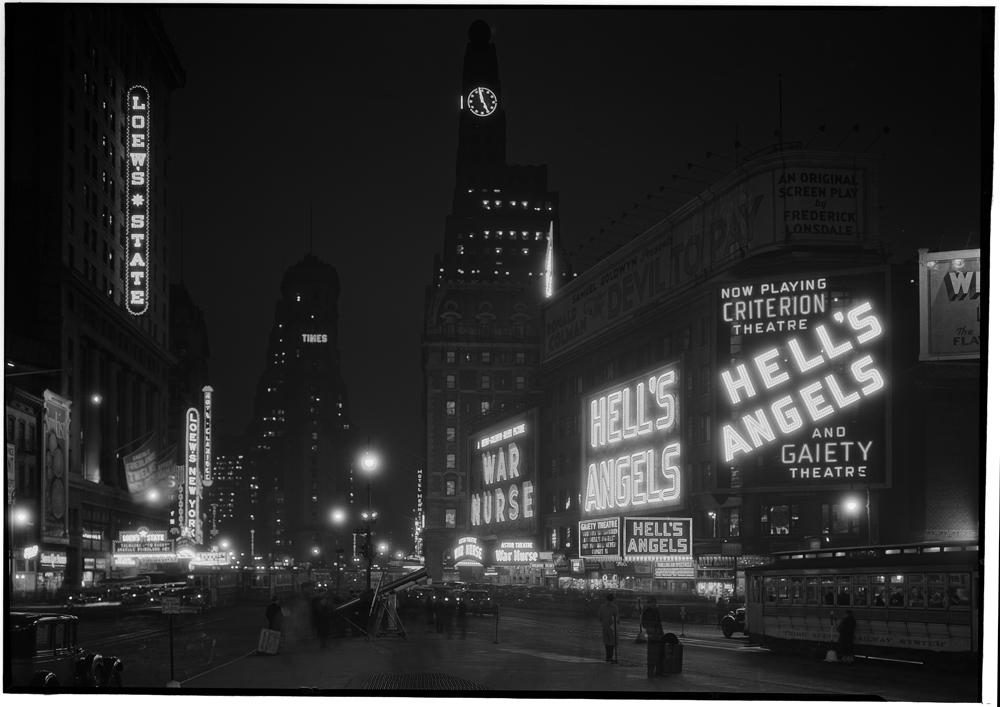

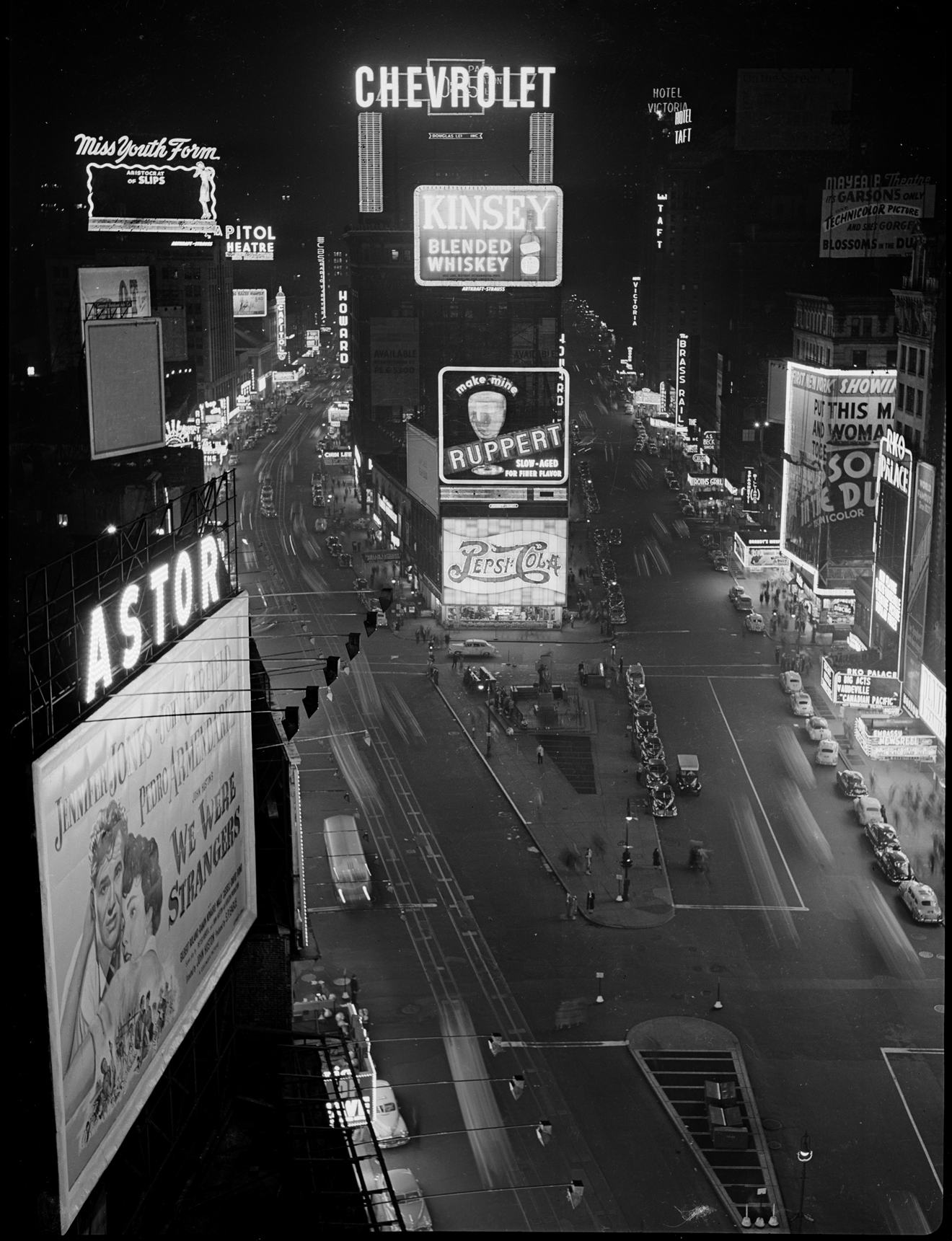

George M. Cohan’s position in Times Square re-emphasizes the districts long association with theater. By World War I, most legitimate theaters had moved to Times Square from former entertainment districts further downtown. Respected restaurants and high-end hotels, like the Astor and the Knickerbocker, established themselves in the neighborhood, thus contributing to a thriving environment. While popular bars, restaurants, and theaters attracted people to the area, it was the development of public transportation that facilitated Times Square’s dramatic growth. For example, in 1905, the first year of operation, the IRT Times Square station serviced almost five million passengers. By the late 1920s, subway lines, elevated lines, and bus routes all stopped at West 42nd Street. It thus became an irrefutable hub of the city, transporting not only city dwellers, but also affluent suburbanites and visitors.

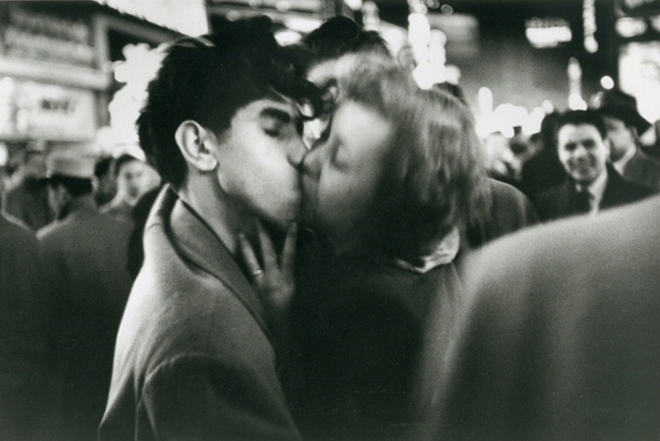

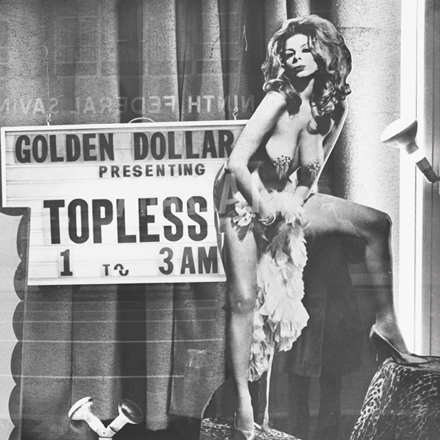

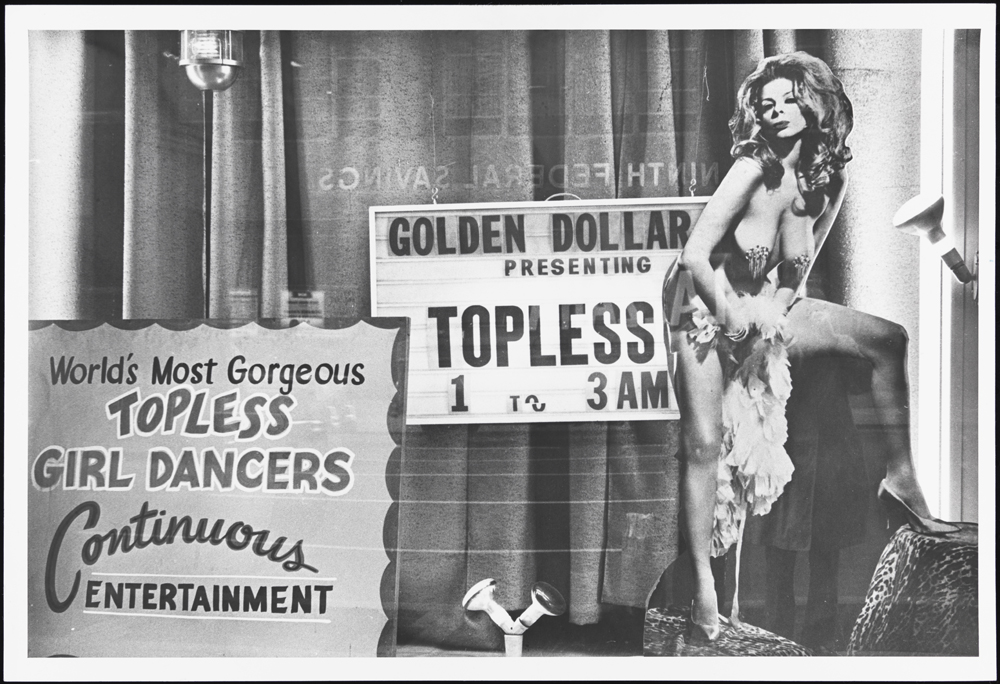

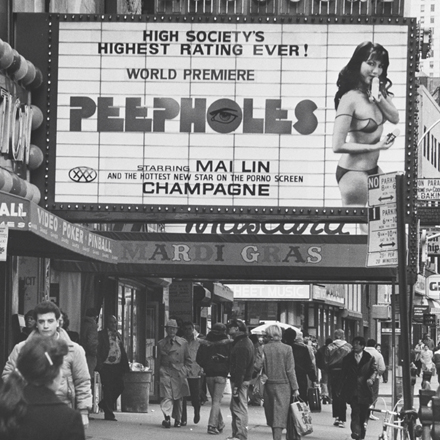

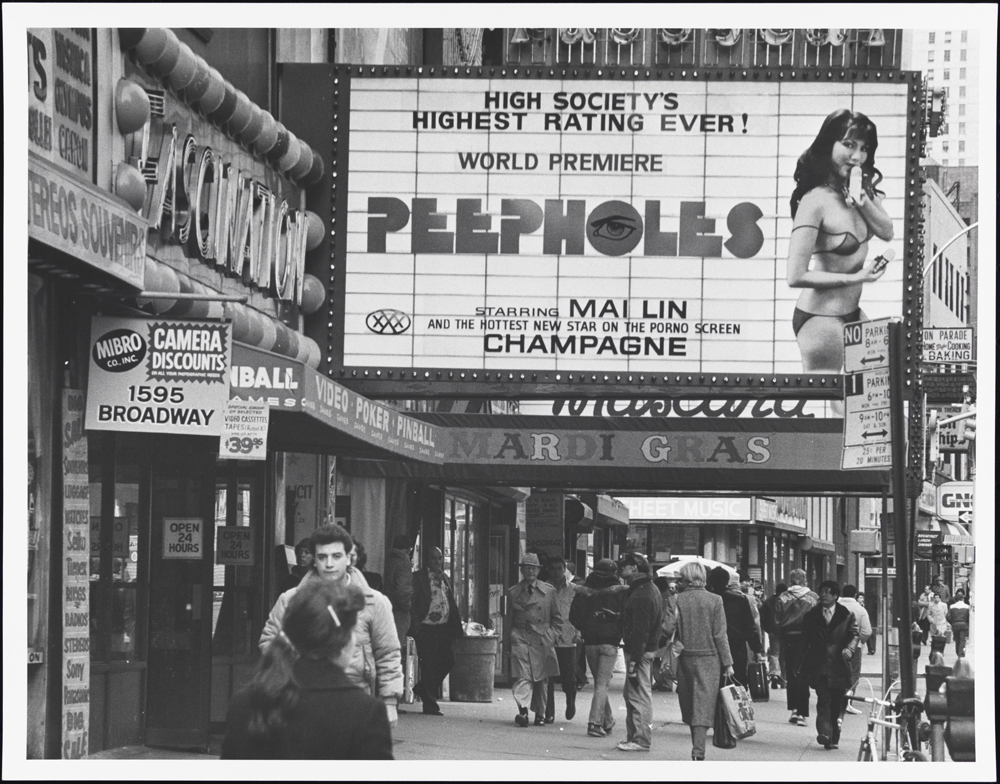

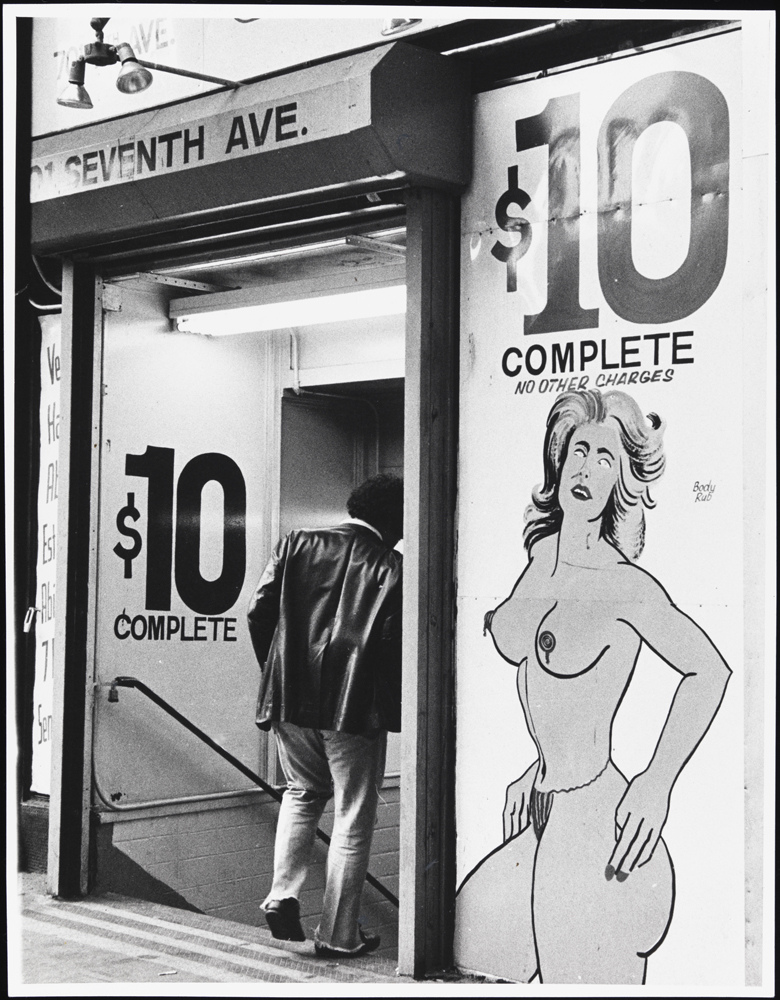

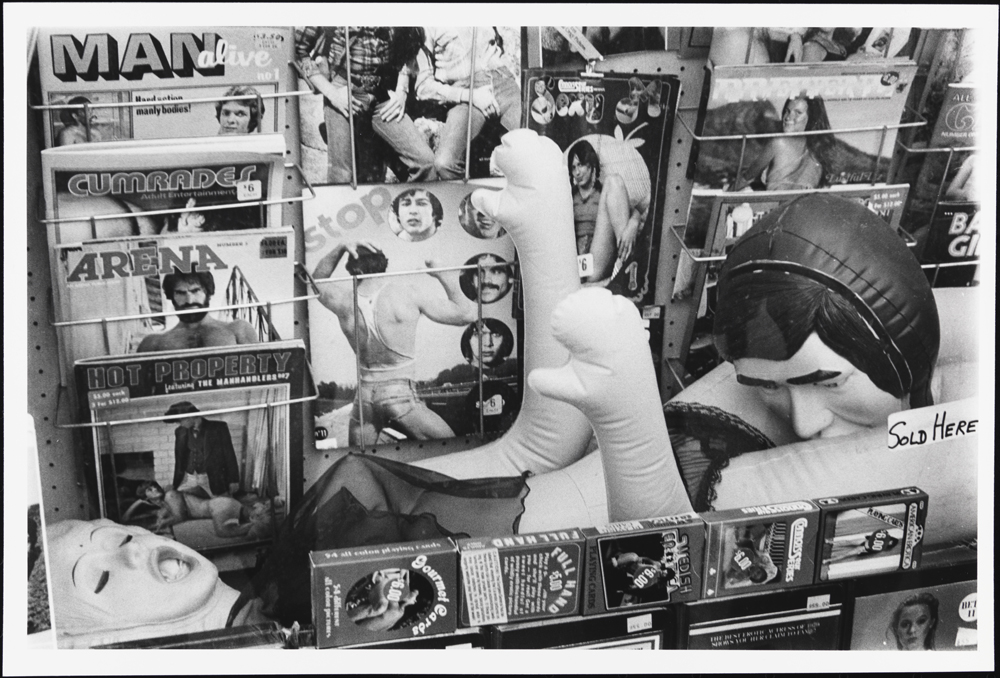

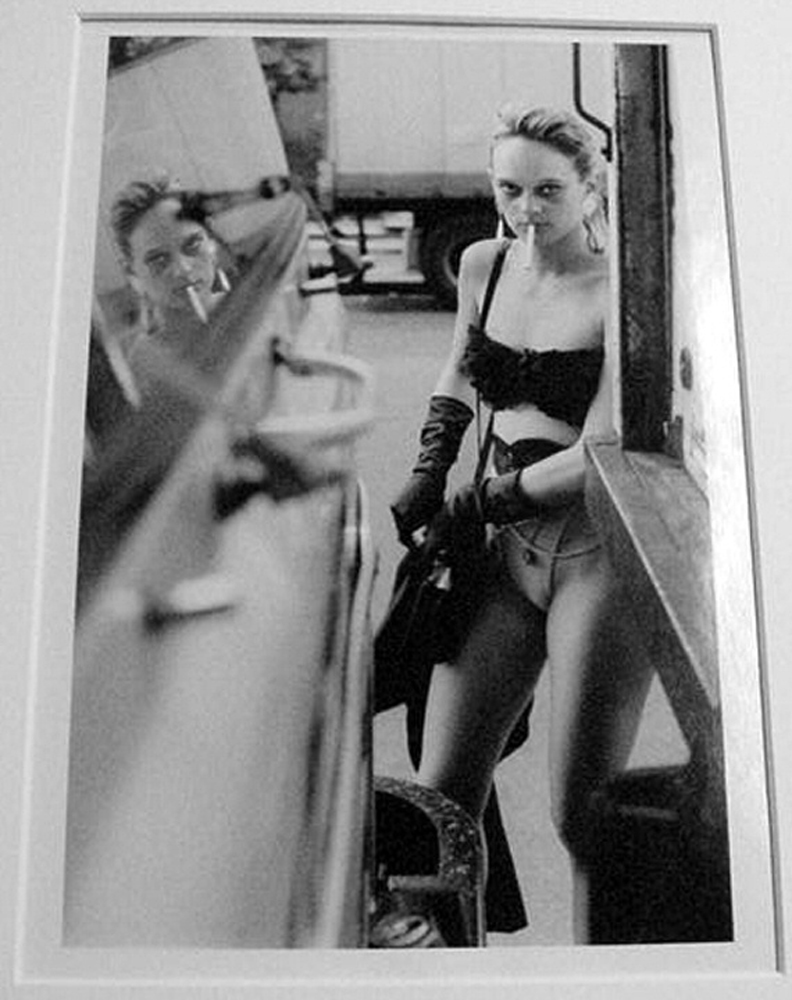

Sadly, the Great Depression hampered this growth. As theaters struggled to survive during this period, many became cheap ‘grinder’ houses that showed sexually explicit films. Soon, other lower forms of entertainment arrived in the area: burlesque shows, cheap restaurants, peep shows, dance halls, and penny arcades. Then, commercialized sex proliferated throughout the neighborhood as both male and female prostitutes began lingering along 42nd Street. The advent of World War II did little to improve Times Square’s reputation. Soldiers on leave, in search of erotic entertainment, further catalyzed the neighborhood into a zone for vice. Likewise, construction restrictions during the war worsened conditions by halting the city’s building boom of the 1920s. Times Square had begun a descent into disrepair and depravity.

World War II had another, very visible effect on Times Square. In May of 1942, Mayor La Guardia announced a dimout. Interior and exterior lighting, in addition to illuminated advertising and building lights, were required to be turned off or directed downward. The order sought to protect pedestrians silhouetted against the horizon from enemy submarines in coastal waters. The dimout was so extensive that the WPA announced that they would place blackout masks on 90,900 traffic lights throughout the city. Likewise, the electric news sign belting the Times Tower went dark for the first time since its debut in 1928. For nearly fourteen years, the sign attracted billions of spectators with the most news-worthy headlines. Frank Powell, one of three electricians tasked with the sign’s maintenance, stated on the night of the dimout: “All I want is to start it up again the night Hitler gets killed. That would tickle me to death.”

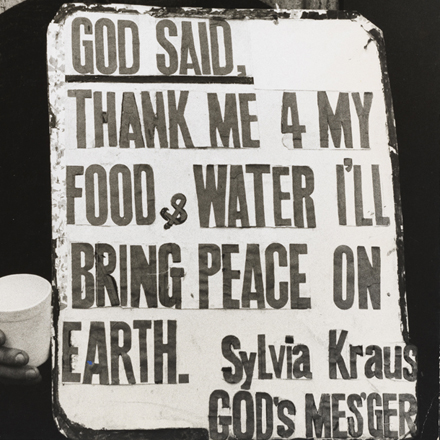

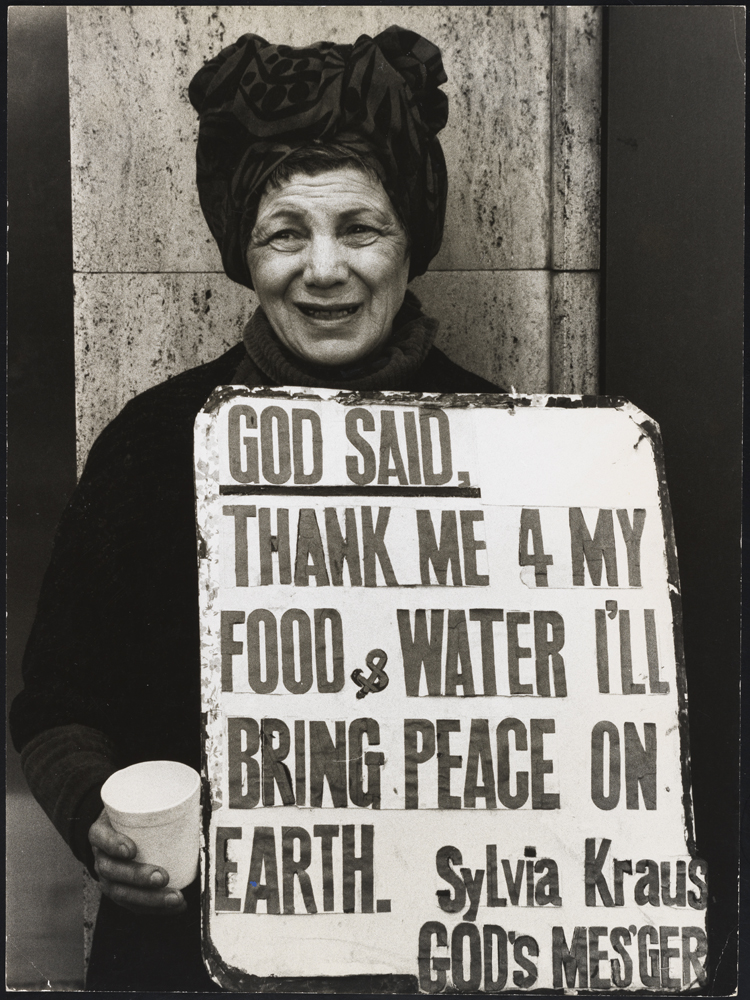

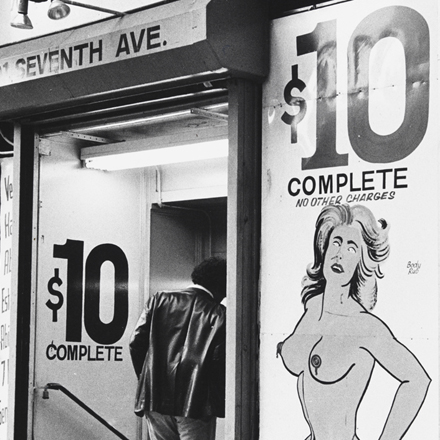

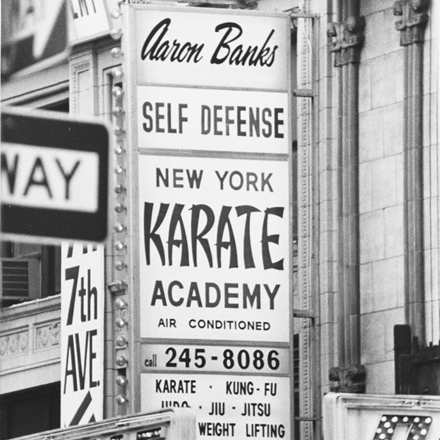

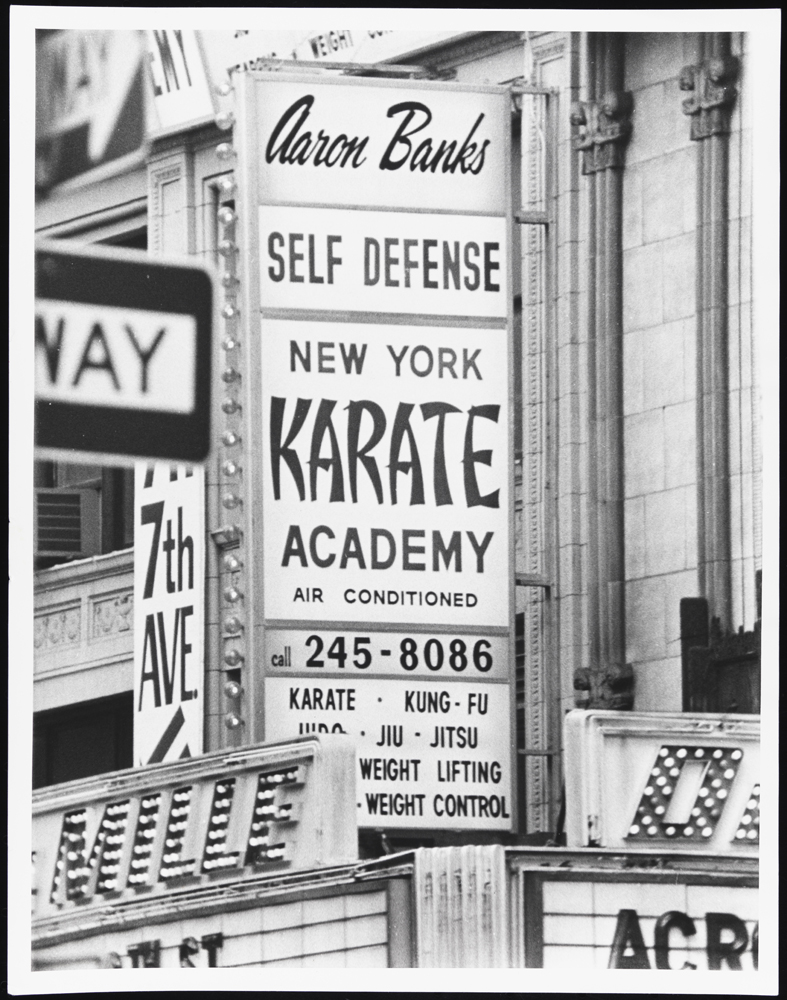

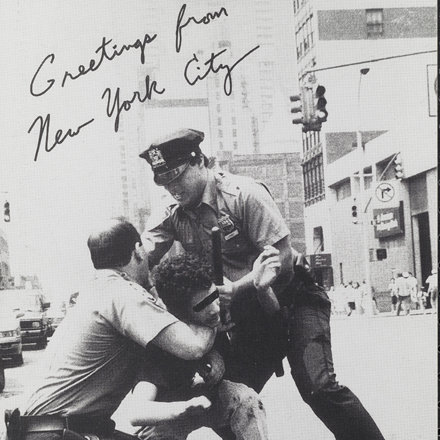

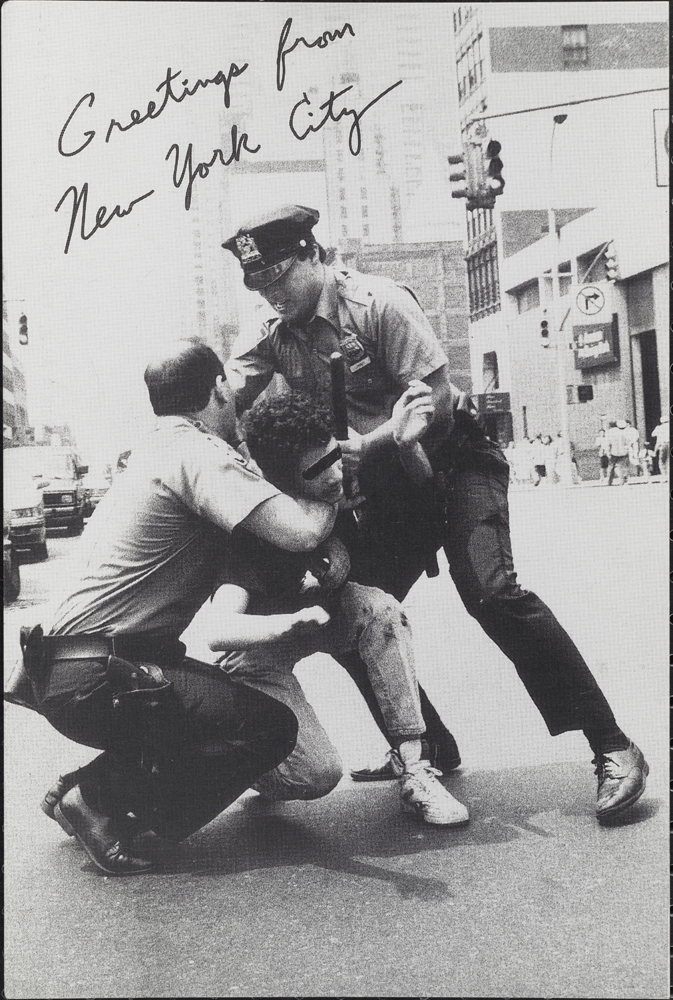

The negative impacts of the Great Depression and World War II on Times Square solidified over time. In the 1950s, attempts to stop the growth of disreputable businesses through zoning rules met with few results. Then the 1960s arrived. As one scholar notes, “the libertarianism of the sixties” changed the meaning of “obscene,” thereby opening a space for the public sale of adult allurements. For example, the success of the twenty-five cent peep show, introduced in 1966, spurred other small businesses to follow the trend by selling adult films and erotic merchandise. Profits rose, the cost of leases sky rocketed, and then the mob “muscled in around 1968.” On the streets, prostitution by all genders, open drug trade, alcoholism, and con games, like three-card monte and clio, became commonplace. Inside, crime thrived in the underground corridors of the subway and the passages at the Port Authority Bus Terminal despite the abundance of police. By the late 1970s, the Times Square area recorded the most felony and net crime complaints in the city. That said, not all activity in the neighborhood was bad; in 1973, the first TKTS booth opened to provide affordable theater admission with the hope of increasing Broadway attendance. Nevertheless, Times Square’s reputation ranked very low in the public consciousness. In 1981, Rolling Stone declared West 42nd Street the “sleaziest block in America.” Likewise, one scholar wrote, “The Great White Way is now a byword for ostentatious flesh-peddling in an open-air meat rack.”

The negative impacts of the Great Depression and World War II on Times Square solidified over time. In the 1950s, attempts to stop the growth of disreputable businesses through zoning rules met with few results. Then the 1960s arrived. As one scholar notes, “the libertarianism of the sixties” changed the meaning of “obscene,” thereby opening a space for the public sale of adult allurements. For example, the success of the twenty-five cent peep show, introduced in 1966, spurred other small businesses to follow the trend by selling adult films and erotic merchandise. Profits rose, the cost of leases sky rocketed, and then the mob “muscled in around 1968.” On the streets, prostitution by all genders, open drug trade, alcoholism, and con games, like three-card monte and clio, became commonplace. Inside, crime thrived in the underground corridors of the subway and the passages at the Port Authority Bus Terminal despite the abundance of police. By the late 1970s, the Times Square area recorded the most felony and net crime complaints in the city. That said, not all activity in the neighborhood was bad; in 1973, the first TKTS booth opened to provide affordable theater admission with the hope of increasing Broadway attendance. Nevertheless, Times Square’s reputation ranked very low in the public consciousness. In 1981, Rolling Stone declared West 42nd Street the “sleaziest block in America.” Likewise, one scholar wrote, “The Great White Way is now a byword for ostentatious flesh-peddling in an open-air meat rack.”

In addition to the sex market, the drug trade also profoundly affected Times Square. Efforts to address the increase in prostitution, especially by juveniles, were derailed by the arrival of crack cocaine to Times Square in 1986. As a result, crime rates spiked and continued to increase through 1989. The addictiveness of crack made it an especially insidious drug, as users focused their energy and resources on scoring the next ‘hit’. Crack dealers, junkies, and the cardboard encampments of the homeless took over the streets.

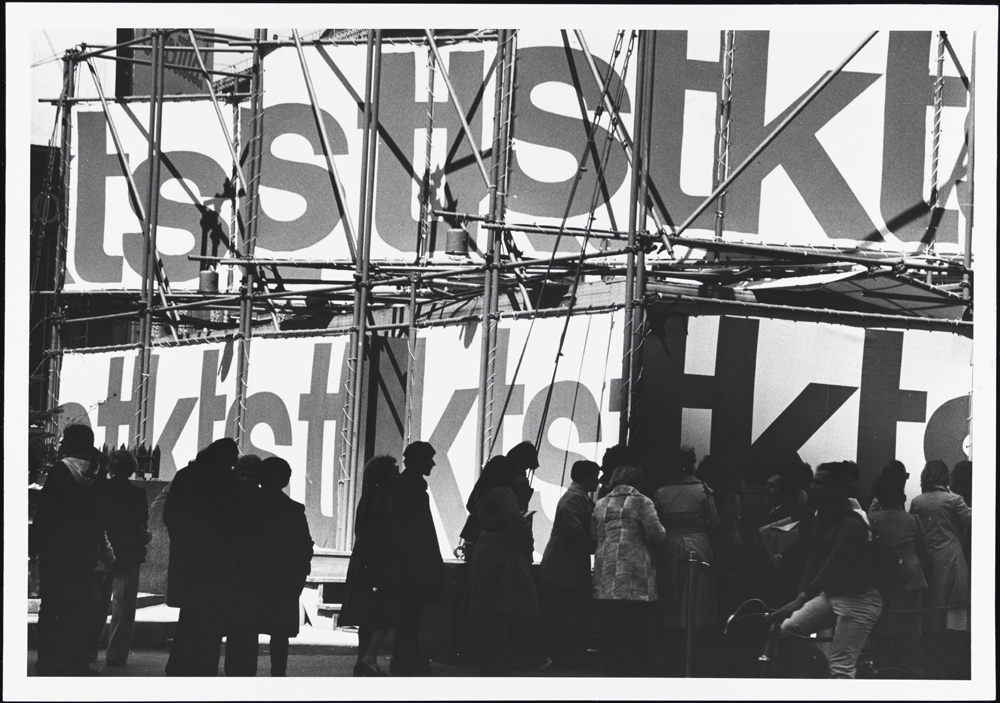

Despite Times Square’s notorious reputation, it managed to maintain its powerful symbolism, in part because of its “chaotic action, dense and diverse pedestrian activity, [and] continuous role as the key entertainment district.” It also remained a central transit hub and offered a “unique physical ‘experience of place,’ which derived from its small-scale buildings, open space, and illuminated lights.” Times Square’s symbolic meaning, therefore, ignited debate and opposition with any proposed plan for renewal.

In addition to the district’s symbolism, efforts at redevelopment also proved challenging, in part, because the adult industry made huge profits. For example, CUNY researchers estimated that the weekly gross of peep shows ranged from $74,000 to $106,000 in 1978. Likewise, property ownership was convoluted as landlords sought to create distance between themselves and those who ran the porno shops and peep shows on their property. The redevelopment project focused on revitalizing 42nd street as a theater and entertainment center. After tremendous time, money, and effort, Times Square slowly began to transform as adult stores and sleazy theaters were replaced by child-oriented stores and successful musicals. As tourist activity increased, Times Square continued to improve. A new TKTS sales center was installed. Further construction stopped vehicular traffic and made the plaza area more inviting to pedestrians. In 2008, the newly designed Duffy Square was re-opened to the public. Times Square has experienced flourishes of creative vibrancy and periods of great depravity, and yet it remains “the crossroads of the world.”

Works Cited

Barron, James. “100 Years Ago, an Intersection’s New Name: Times Square.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 07 Apr. 2004. Web. 07 July 2015.

“Drastic Dimout of All City Lights Effective Tonight.” The New York Times 18 May 1942: n. pag. The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 7 July 2015.

“Father Duffy Square.” Father Duffy Square. NYC Parks, n.d. Web. 07 July 2015.

McNamara, Robert P. Sex, Scams, and Street Life: The Sociology of New York City’s Times Square. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1995. Print.

McNamara, Robert P. The Times Square Hustler: Male Prostitution in New York City. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994. Print.

Sagalyn, Lynne B. “Mediating Change: Symbolic Politics and the Transformation of Times Square.” University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons (2001): n. pag. Penn Libraries. University of Pennsylvania. Web. 7 July 2015.

Sagalyn, Lynne B. Times Square Roulette: Remaking the City Icon. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2001. Print.

Taylor, William R. “Times Square.” The Encyclopedia of New York City. Ed. Kenneth T. Jackson. Second ed. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2010. 1316-318. Print.

“Text of Dimout Order.” The New York Times 18 May 1942: n. pag. The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 7 July 2015.

“The Times Electric News Sign Goes Dark Under New Dimout, Probably for Duration.” The New York Times 19 May 1942: n. pag. The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 7 July 2015.

![Robert L. Bracklow (1849-1919). [Policeman in front of monument entitled “Defeat of Slander”], 1910. Museum of the City of New York. 93.91.233](/sites/default/files/93-91-233 thumbnail.jpg)

![Robert L. Bracklow (1849-1919). [Policeman in front of monument entitled “Defeat of Slander”], 1910. Museum of the City of New York. 93.91.233](/sites/default/files/93-91-233.jpg)

![Byron Company. [Broadway Theatre.], 1895. Museum of the City of New York. 29.100.1182](/sites/default/files/29-100-1182 thumbnail.jpg)

![Byron Company. [Broadway Theatre.], 1895. Museum of the City of New York. 29.100.1182](/sites/default/files/29-100-1182.jpg)

![Samuel Herman Gottscho (1875-1971). New York City views. Times Square from 41st Story [of the] Continental Building, at night, February 16, 1932. Museum of the City of New York. 88.1.1.2206](/sites/default/files/88-1-1-2206 thumbnail.jpg)

![Samuel Herman Gottscho (1875-1971). New York City views. Times Square from 41st Story [of the] Continental Building, at night, February 16, 1932. Museum of the City of New York. 88.1.1.2206](/sites/default/files/88-1-1-2206.jpg)

![Charles Ditchfield (no dates). Mary Gets Going. [Soldiers and girl dancing in Times Square.], ca. 1945. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.4027](/sites/default/files/x2010-11-4027 thumbnail.jpg)

![Charles Ditchfield (no dates). Mary Gets Going. [Soldiers and girl dancing in Times Square.], ca. 1945. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.4027](/sites/default/files/x2010-11-4027.jpg)

![J.G. Suter (no dates). Gone but Not Forgotten. [Times Square during Dim-out.], ca. 1945. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.4013](/sites/default/files/x2010-11-4013 thumbnail.jpg)

![J.G. Suter (no dates). Gone but Not Forgotten. [Times Square during Dim-out.], ca. 1945. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.4013](/sites/default/files/x2010-11-4013.jpg)

![Unknown. [Sailors and woman in Times Square.], ca. 1945. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.3996](/sites/default/files/x2010-11-3996 thumbnail.jpg)

![Unknown. [Sailors and woman in Times Square.], ca. 1945. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.3996](/sites/default/files/x2010-11-3996.jpg)

![Alfred Mainzer (no dates). [Times Square], ca. 1980. Museum of the City of New York. F2011.33.149](/sites/default/files/f2011-33-149_1.jpg)

![Leland Bobbé, Subway [Voice of the Ghetto], 1974. Archival pigment print. Gift of the photographer. 2016.10.7.](https://www.mcny.org/sites/default/files/styles/mcny_col_3_thumbnail/public/mn185974_0.jpg?itok=8q3-MZ35)