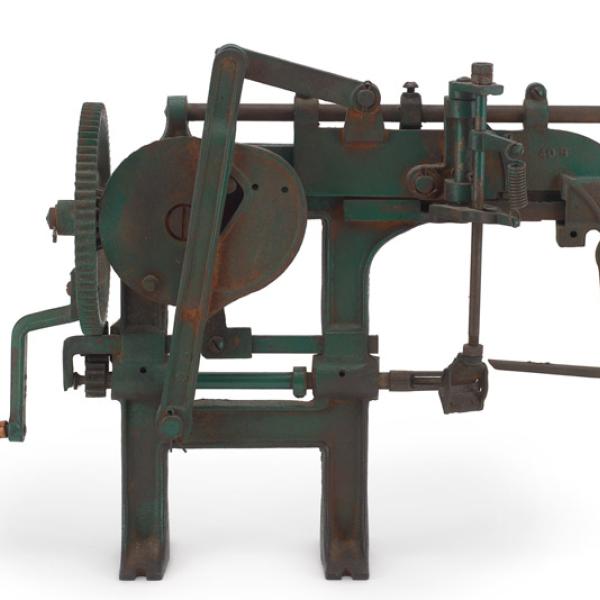

Lenape Ceremonial Club

Object Essay

Monday, November 14, 2016 by

We don’t know exactly who carved this ornamented wooden club, but we surmise it was given by a Lenape person to a European one. The wood is likely from a hickory tree; the ornamentations are shells and copper. The shells could be oyster or clam and relate to the Lenape practice of making and giving wampum, belts of laboriously carved shell beads that were considered extremely difficult to make and therefore precious. The copper was likely of European origin, either cut from trade goods like kettles or gathered from shipwrecks. Carved notches along the nose and above the eyes of the face carved into the clubhead may refer to paint on the face of a warrior or tattooing or scarification. The top knot mimics traditional male hair dressing and head shaving, it is in the shape of a lizard or a snake. The foot on the handle completes the personification of this club; although the club may symbolize a warrior, this was given as a gift and is believed to have been used for ceremonial and diplomatic purposes.

It may have been given as gesture of good faith or as part of a now lost understanding between the Swedes and their neighbors. This club appears to have been presented to Johan Björnsson Printz, the 400-pound, third governor of the New Sweden colony on the Delaware River, sometime between 1642 – 1654. Printz, locally known as “Big Belly”, contributed several objects to the collection of the Skokloster Castle and Armory in Sweden, from which this club has been borrowed. The story of the club and the craft of the people that made it remind us that long before Europeans showed up, New York and New Jersey had already long been a place that people called home.

The Lenape (later called the Delaware) inhabited the stretch of the Atlantic Coast from eastern Pennsylvania to southeastern New York, including the mouth of the Hudson River, and western Long Island, the area that would someday become New York City, in the early 17th century. Speaking an Eastern Algonquin language – the dialect on Manhattan was most likely Munsee, thus giving rise to another name for the Lenape people and the name for Muncie, Indiana. The ancestral Lenape walked and hunted in the same precincts as today’s tall buildings and sprawling suburbs for a thousand years or more before Europeans like Printz, De La Warr, Hudson, or Minuit showed up to trade with and eventually expel them. The Lenape, may have lived here for a thousand years before European contact, were only the last in a series of cultures that lived along this part of the North American shore for the past eight millennia.

In the Late Woodland period (900 – 1600 CE), the Lenape organized in consensually governed small bands. They had no prince and no king. They practiced a horticultural and hunting & gathering lifestyle. They cleared and planted gardens of the “three-sister” combination of corn, beans, and squash, crops domesticated in meso-America, whose seeds and cultivation requirements were traded hand-to-hand to the north. They hunted deer, bear, fowl, and other wildlife, and were expert fisherfolk, utilizing the spring and fall fish runs and collecting oysters, clams, and other sessile marine life. In the woods and marshes, they gathered wild plants for materials and medicines and depended on the vast timber resources of their woodland home to build dugout canoes and rounded shelters of saplings and bark, wigwams, and long houses. They had a rich oral culture, but no written language, and a spiritual connection to land, waters and seasons, reinforced by daily experience, that combined with an ideology that expressed continuity, humility, and generosity.

Lenape ideology didn’t last in the face of European aggression. In New Amsterdam, trouble had been brewing between the Dutch and Lenape after Governor Willem Kieft arrived in 1638 and insisted on collecting tribute from the local Lenape bands. At the same time, the Lenape found the pigs and cows wandering across the unfenced landscape a pest in their corn fields and fair game for hunting. Disagreements mounted into conflicts which led to massacres of Lenape people in Pavonia (later Jersey City) and Corlear’s Hook (later the Lower East Side) in February 1643. Reprisal attacks occurred on both sides over the next decade, including awful incidents of torture and mutilation of the dead, and warfare practiced with a combination of European and American weaponry, including muskets, bows, arrows, steel knives, and wooden clubs, not unlike this one. Although a tentative peace returned in the 1650s, after English colonials from Connecticut assisted the Dutch in bringing “Kieft’s War” to an end by burning every Lenape village they could find. It was the beginning of the end for the Lenape in the region, and as it turned out for Printz and the Swedes, who were supplanted by the Dutch in 1655, and then for the Dutch, who yielded to English gunships in 1664.

Though some Lenape would continue to live in the region into the 18th and 19th centuries, many were forced west under pressures from European settlement. Promised land in the Ohio River Valley, the Lenape were caught between the British and French during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), and then between the Americans and the British during the American Revolution (1775–1783). Christianity also divided the Lenape, as some took to the new religion, while others adhered to traditional beliefs. The young United States government launched what is known as Tecumseh's War (1811 – 1813) in the Old Northwest, forcing another migration. Some moved to what would someday be Missouri and Indiana, others moved to Canada, while others left for Texas and the Wisconsin territory. Today Lenape tribes are federally recognized in Oklahoma and Wisconsin, and Canada recognizes Lenape First Nations with reservations in southwestern Ontario. Many individuals, families and groups have returned to their ancient territories in the Eastern United States, an indelible part of the past, present, and future of New York City.

Further reading

- Cantwell, A.-M., Wall, D. diZerega, 2001. "Unearthing Gotham: The Archaeology of New York City", Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

- Goddard, I., 1978. Delaware, Pages 213–239 in: "Handbook of North American Indians", Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

- Grumet, R.S., 1981. "Native American place names in New York City", Museum of the City of New York, New York.

- Kraft, H.C., 2001. "The Lenape-Delaware Indian heritage: 10,000 B.C.- A.D. 2000", Lenape Books, South Orange, N.J.

- Lipman, Andrew. "Saltwater Frontier. Indians and the Contest for the American Coast",Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2015.

- Sanderson, E.W., 2009. "Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City", Abrams, New York.

- Weslager, C.A., 1989. "The Delaware Indians: A History", Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N.J.

We asked the author, why study history?

I’m obsessed with how the future comes to be. History provides practically infinite number of case studies of how human values, understanding and decisions created our world and suggests the world we creating for the future.