Future City Lab: What If?

Questioning What We Know

Interdisciplinary

Time Estimate: 1 hour

Objectives:

Students will:

- practice critical thinking based on real-world issues facing New York City

- weigh and evaluate strategies and consequences

Materials:

- Presentation (provided)

- Computer-connected projector

Standards:

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.1: Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.3: Evaluate a speaker's point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.4: Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

Guiding Questions:

- What are the “right kinds” of questions to ask when thinking about a problem?

- What problems do New Yorkers face specific to them as residents of this city and what approaches can be used to solve them?

- Step 1: Introduction (5 minutes)

- Step 2: Group Discussion (30 minutes)

- Step 3: Small Group Work (10 minutes)

- Step 4: Share Out and Conclusion (15 minutes)

Procedures

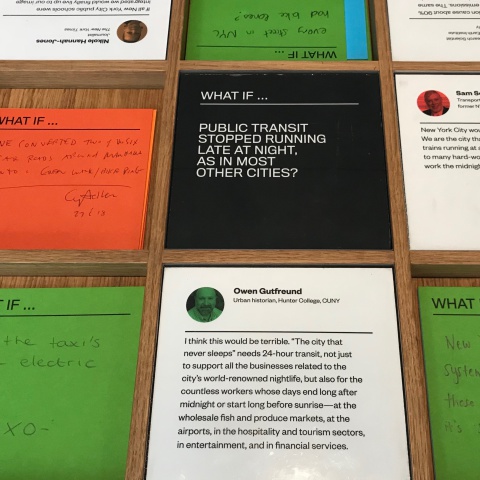

This lesson is inspired by the Museum’s Future City Lab, in which visitors are introduced to the challenges facing New York City and strategies that can be used to solve them. The “What If?” table at the entrance of the gallery, which encourages visitors to pose questions to the Museum and each other, signals the interactive nature of the Future City Lab and encourages visitors to think of themselves as participants in future problem-solving. Questions are reviewed by the Lab’s Director and experts are asked to respond to the public’s questions as part of an evolving discussion.

This lesson asks students to review a selection of Museum visitors’ “What If?” questions and then develop their own as part of a problem-solution framework that encourages specificity and critical thinking. (Note: this lesson can easily be scaled up or down according to grade level at the discretion of the teacher.)

For more on the Future City Lab, see http://www.mcny.org/exhibitions/core/future-city.

Use the presentation to introduce the concept of a “What If?” question to your students. You might note that a “What If?” question is like a scientist’s hypothesis: something to ask, test, and incorporate into a larger explanation or worldview.

Using a computer-connected projector, visit the Museum’s “What If?” landing page. The Museum will be adding more options to this site periodically, but this lesson focuses on two: What If…Immigrants stopped coming to New York?,and What If…New York City relied on 100% renewable energy sources?. (Note that a third question – What If…Schools selected their students to reflect the racial and economic diversity of the city? – is also available but might be deemed difficult for younger students. Teachers are encouraged to review all questions in advance.)

Lead students through each “What If?” series (be sure to click in to the main page of each question for full details, including the original visitor questions and experts’ responses). Note that the main question is a combination, or synthesis, of questions asked by at least three different visitors. (Note, too, that you may need to define problems and terms according to your class’s grade and knowledge level – scale up or down within the “What If?” framework and only use those examples that work for your class.)

For each “What If?” series, complete the following steps:

1.) Review each visitor question. How are they different?

2.) Most “What If?” questions posed by visitors are asked because there is a problem. What problem is this “What If?” question trying to address?

3.) What do we know about the current state of that problem in New York City? How can we find out more so we can be more knowledgeable? (Note: students can research any of these issues as part of a class extension activity.)

4.) Review each expert response. How are they different? Are there any clues about this person’s point of view? (Note that each expert’s affiliation or credentials are listed at the top of their response.)

5.) Which expert’s response do you find most convincing? Have any of the responses changed your own thinking on the topic?

6.) Can we discuss the issue as a group and try to think of more results (“Then…”) from the “What If?” What more do we need to know to do this?

Have students work in small groups to formulate their own “What If?” questions. Before beginning, be sure to use the presentation to model effective and ineffective questions. Encourage students to be specific and to break large problems into smaller, more solvable components. Each student can come up with their own question, using the advice and feedback in their group to hone the wording and think through possible outcomes. Students are asked to consider:

1.) What problem would I like to solve?

2.) What specific approach (or strategy) could be used to address it?

3.) What are the approach’s likely benefits (the “pros”)?

4.) What are its likely downsides (the “cons”)?

5.) Given the pros and cons, is the overall outcome likely to be good or bad?

Then have students write their own “What if?…/Then…” questions. (Note that younger students might create more specific proposals by thinking of the question as a “What if we…” instead of a simple “What if…”)

Have students share out possible “What Ifs?” and discuss them as a class. Encourage students to learn more about their topics and to think of and learn about alternative approaches to solve their problem. (Useful resources for this kind of work will vary widely given the problems and solutions that students identify, but if students remain focused on questions of urban planning, the website of the Regional Planning Association highlights the key problems and strategies currently under debate.)

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Jessica Lahey, “What Kids Can Learn from Urban Planning,” City Lab, January 4, 2017: https://www.citylab.com/life/2017/01/what-kids-can-learn-from-urban-planning/512183/

Fieldtrips: This content is inspired by the Future City Lab gallery in the Museum’s flagship exhibition, New York at Its Core. If possible, consider bringing your students on a fieldtrip! Visit http://mcny.org/education/field-trips to find out more.

Acknowledgements

This series of lesson plans for New York at Its Core was developed in conjunction with a focus group of New York City public school teachers: Joy Canning, Max Chomet, Vassili Frantzis, Jessica Lam, Patty Ng, and Patricia Schultz.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in these lessons do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.